The Bow Street Runners were the first professional police force, organised in London by magistrate and author Henry Fielding in 1749. The group would end up successfully solving and preventing crimes until 1839 when the force was disbanded in favour of the Metropolitan Police, leaving behind a legacy for modern-day policing.

Before the introduction of the Bow Street Runners and anything of the like, policing took the form of privately paid individuals used to maintain law and order without a formal system connected to the state. This resulted in unofficial policemen who were known as ‘Thief Takers’ who would capture criminals for money and negotiate deals in order to return stolen goods whilst claiming rewards. People who partook in this activity, such as a figure called Charles Huitchen and his accomplice Jonathan Wild, were voluntarily policing the streets of London for big profits when in fact, these men and others like them were often behind much of the crime in the area. The informal, volunteer based system was not working.

The increasing crime rate prompted the government to increase the rewards on offer to around £100 for the arrest of a highwayman, someone who robbed travellers, often on horseback. The increase was considerable from the £40 offered in 1692 for the conviction of such a criminal. The resulting impact was a swelling number of private thief-takers operating around London, rather than the intended consequence of incentivising victims to prosecute the person who had carried out the crime.

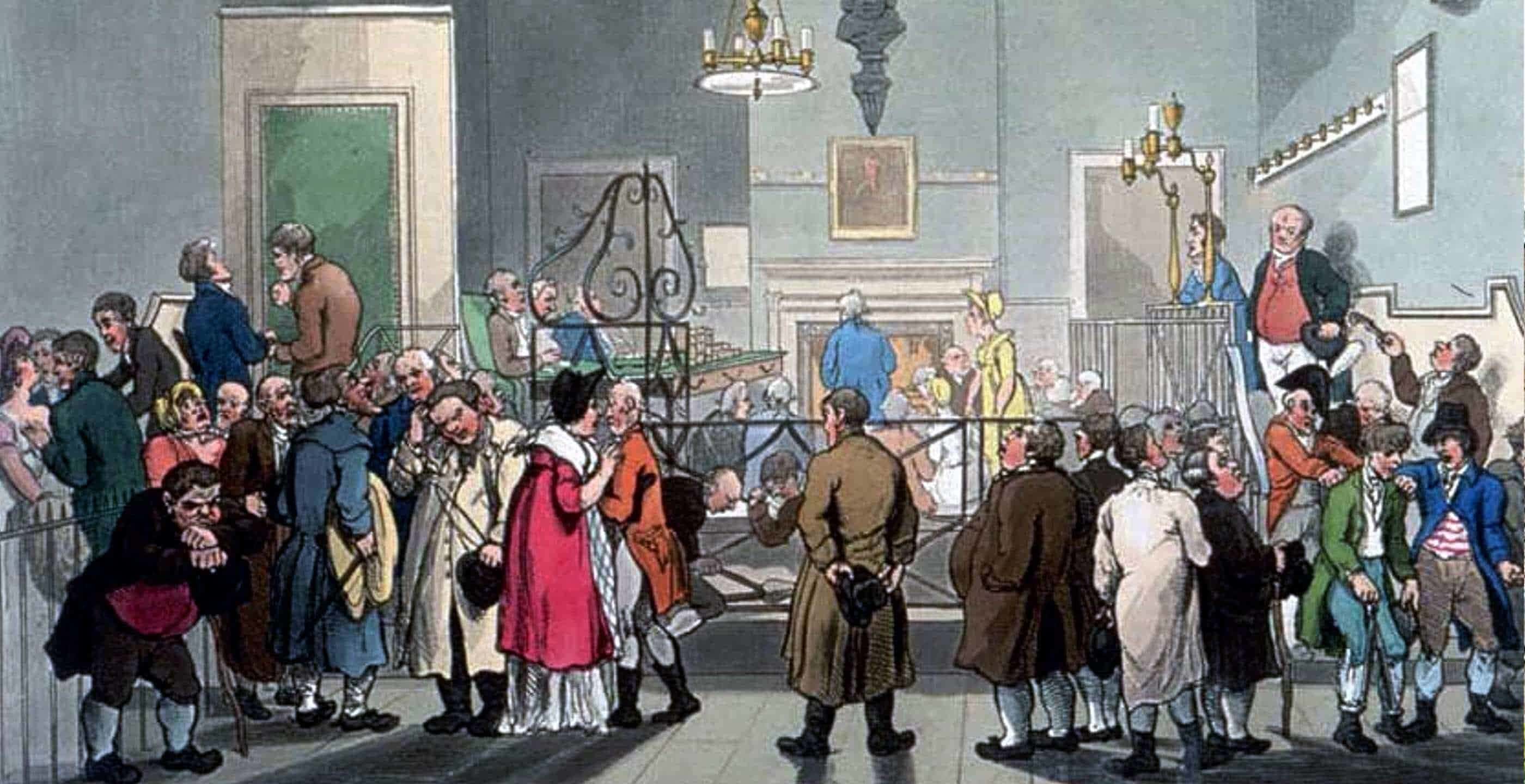

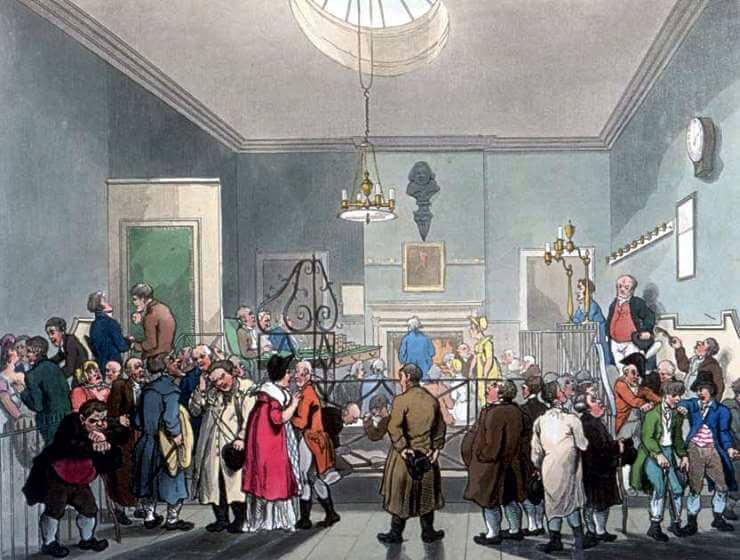

It was clear that the system in place was not functioning as it should, with crime still on the increase and new crimes developing, something new had to be done. The law enforcement in operation in the eighteenth century had changed very little since medieval times. There were JPs, known as Justices of the Peace that had been in existence since 1361, appointed by the Crown but were often known for their corruption. Then there were the watchmen, referred to as ‘Charleys’ because they were introduced by King Charles II, but had proved to be predominantly ineffective. The constables meanwhile, were often only working part-time and were paid very little and therefore had little incentive to meet the requirements of their job.

With London growing rapidly and crime accompanying this growth, Henry Fielding, the chief magistrate at Bow Street Court decided to conduct and write a report about the crime rates in the capital and published his findings in 1751. The report found that the increase in crime could be attributed to a number of factors, including a great number of people moving to London expecting an easy life, inherent corruption within the government, people choosing crime over hard work and the ineffectual constables. With these findings published, Fielding sought to bring about some necessary changes to law enforcement.

Henry Fielding, along with his half-brother John who was also a magistrate, founded the Bow Street Runners, a paid police force with the intention of preventing and fighting crime. Henry was known for his motto of ‘quick notice and sudden pursuit’. He was keen to use the general public to help, somewhat similarly as before, by using adverts and pamphlets asking for assistance.

The force he set up included six paid constables to patrol the streets of London. The name the Bow Street Runners referred simply to their location, whilst the term ‘runners’ referred to their pursuit of criminals, although it was not a name that was particularly well-received by the constables themselves.

The constables were formally trained, paid and full-time serving officers, very different from the more informal, privately funded system which had been operating. Instead the men were paid using a government grant, therefore creating a closer link to a state-run law enforcement system. They were also to receive rewards when they caught their suspects, much like the Thief Takers, only with more formality and control in place. This idea proved to be effective and by 1800, there were said to be around sixty-eight Bow Street Runners fighting crime in London.

The police force was essentially London’s first professional police force of its kind, using organised methods of dealing with crimes, formal work settings and a proper law enforcement system. The Bow Street runners differed from their ‘thief-taker’ predecessors because they were not only formally attached to the Bow Street magistrates office, but they were also paid by central government. Much of the work was being conducted from Henry Fielding’s own office and the court at No. 4 Bow Street. The constables would arrest offenders on the authority of the magistrates and would travel across the country in pursuit of the criminals.

Henry Fielding dedicated himself to making the streets of London safe again. He went about setting up a journal called the Covent Garden Journal, containing information about criminals and their activity, much like an eighteenth century version of “Crimewatch”. It served to make people aware, allowing them to assist in solving a crime and operating almost as a neighbourhood watch, helping to reduce the likelihood of a crime being committed.

Henry died in 1754 and his brother John succeeded him, continuing his good work as magistrate. Although blind, John took over the reins and successfully managed Henry’s legacy, remaining the Chief Magistrate for the next twenty-six years. He served until 1780 and it was said that he could recognise the voice of over 3,000 criminals.

John Fielding managed to acquire a government grant in order to set up the horse patrol which had been organised by his brother, helping to deal with the issue of highway robberies. The use of grants, however temporary, was an important step in increasing the government’s involvement in law enforcement. Under John Fielding, the Bow Street Runners gained more recognition from the government, as they became more aware of the methods and structure that could be achieved with formal policing. Bow Street represented the professionalisation of the police force.

John would continue his brother’s legacy by using his idea of involving the general public in order to assist in crime prevention. He published ‘The Quarterly Pursuit’, a newspaper produced every week, providing information on stolen goods and giving descriptions of criminals. The idea of sharing information to solve crime spread nationwide.

The Bow Street Runners even helped to uncover the Cato Street Conspirators, a group attempting to kill the British cabinet members as well as the Prime Minister in 1820. By using an informer, the police force managed to trap the conspirators, arresting thirteen men whilst one policeman was killed in the confrontation. The uncovering of such a plot was a major coup for the Bow Street Runners, demonstrating the enormous impact they had on the prevention of crime.

Nevertheless, the Bow Street Runners were eventually replaced in 1829 with the formation of the Metropolitan Police. They would eventually disband entirely in 1839 after decades of pioneering police work tackling criminal activity on the streets of London.

The Bow Street Runners were a pioneering force, revolutionising the way law enforcement was carried out. Henry Fielding and his brother John helped to introduce a new way of policing in a formalised setting with government support, which would form the backbone of future police work to come. Modern-day policing owes a great deal to the first tentative steps taken in reinventing law enforcement in eighteenth century England.

Jessica Brain is a freelance writer specialising in history. Based in Kent and a lover of all things historical.