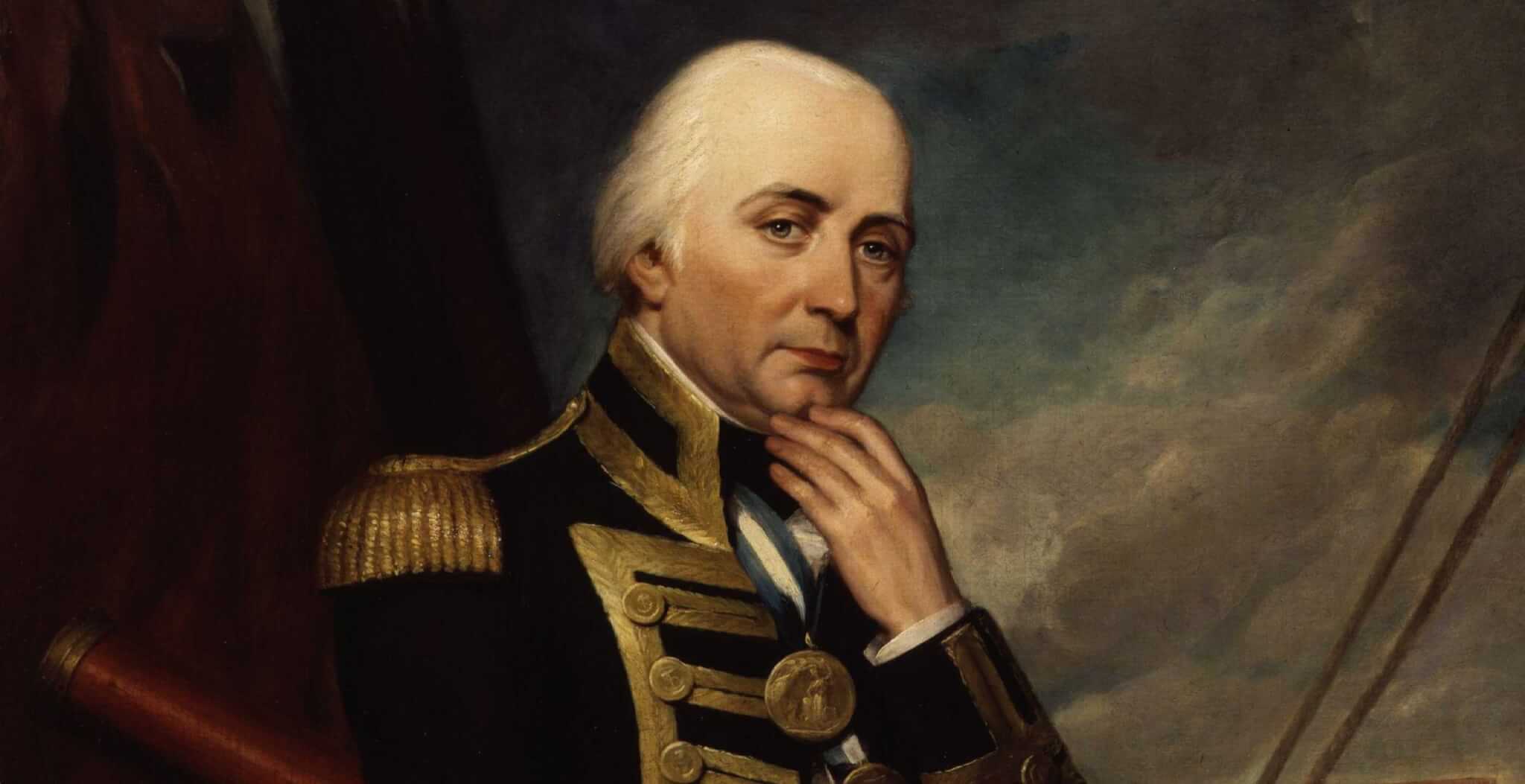

The year was 1797. It had been more than a year since the Spanish switched sides and joined the French, thus seriously outnumbering the British forces in the Mediterranean. Consequently, the First Sealord of the Admiralty George Spencer had decided that a Royal Navy presence in both the English Channel as well as in the Mediterranean was no longer viable. The subsequently ordered evacuation was executed swiftly. The respected John Jervis, affectionately nicknamed “Old Jarvie”, was to command the battleships stationed at Gibraltar. His duty consisted of denying the Spanish fleet any access to the Atlantic where they might wreak havoc in cooperation with their French allies.

It was – once again – the same old story: Britain’s nemesis had set her sights on an invasion of the isles. They almost succeeded in doing so in December 1796 were it not for bad weather and the intervention of Captain Edward Pellew. British public morale never had been so low. Thus, strategic considerations as well as the need to alleviate the dampened spirits of his compatriots, filled Admiral Jervis’ mind with an urge to inflict a defeat upon the “Dons”. This opportunity arose as no one other than Horatio Nelson appeared on the horizon, bringing the news of the Spanish fleet being on the high seas, most likely bound for Cadiz. The admiral immediately weighed anchor to bear down on his enemy. Indeed, Admiral Don José de Cordoba had formed an escort force of some 23 ships of the line to convoy some Spanish freighters, carrying precious mercury from the American colonies.

On the hazy morning of 14th February Jervis in his flagship HMS Victory sighted the vast enemy fleet which appeared like “thumpers looming like Beachy Head in a fog”, as one Royal Navy officer put it. At 10:57 the admiral ordered his ships to “form a line of battle as convenient”. The discipline and speed with which the British executed this manoeuvre baffled the Spanish who were struggling to organize their own ships.

What followed was a testimony of the poor state of Don José’s fleet. Unable to replicate the British, the Spanish warships hopelessly drifted apart into two untidy formations. The gap between these two groups presented itself to Jervis as a gift sent from heaven. At 11:26 the admiral signalled “to pass through the enemy’s line”. Special credit goes to Rear Admiral Thomas Troubridge who pressed on his leading ship, the Culloden, despite the dangers of a fatal collision, to cut off the Spanish vanguard from the rear which was under the command of Joaquin Moreno. When his first lieutenant warned him of the peril, Troubridge replied: “Can’t help it Griffiths, let the weakest fend off!”

Shortly thereafter, Jervis’ ships raked the Spanish rearguard to leeward one by one as they were passing them by. At 12:08 His Majesty’s Ships then tacked orderly in succession to pursue the Dons’ main battle group to the North. After the first five battleships had passed Moreno’s squadron, the Spanish rear began to counterattack Jervis. Consequently, the British main battlefleet was in danger of becoming isolated from Troubridge’s vanguard which was slowly nearing Don José de Cordoba’s numerous vessels.

The British admiral quickly signalled to the ships astern – under the command of Rear Admiral Charles Thompson – to break formation and turn to the West, directly towards the enemy. The entire battle depended on the success of this manoeuvre. Not only were Troubridge’s front five ships seriously outnumbered, moreover it appeared as if Don José was to maintain an eastern heading in order to rendezvous with Moreno’s squadron.

If the Spanish admiral succeeded in bringing his whole force together, this numerical superiority could prove disastrous for the British. On top of this, poor visibility brought another issue: Thompson never received Jervis’ flagged signal. This was, however, exactly the sort of situation the British admiral had trained his officers for: when tactics and communication failed, it was up to the commanders’ initiative to save the day. Such approach to naval battles was completely unorthodox at the time. The Royal Navy had indeed degenerated into a formalistic institution, obsessed over tactics.

The Battle of Cape St. Vincent fleet deployment at about 12:30 p.m.

The Battle of Cape St. Vincent fleet deployment at about 12:30 p.m.

Situation around 1:05 p.m.

Situation around 1:05 p.m.

Nelson in his HMS Captain sensed that something was completely amiss. He took matters into his own hands and without observing the admiral’s signal, he broke off from the line and headed towards the West to aid Troubridge. This movement sealed Nelson’s fate to become the Royal Navy’s darling and the national hero of Great Britain. As a lone wolf he was bearing down on the Dons while the remainder of the rear was still in doubt over what next step was to be taken.

After a while, however, the rearguard followed suit and set their course towards Cordoba. By then, the outnumbered HMS Captain had taken a heavy battering by the Spanish with most of her rigging as well as her wheel being shot to tatters. But her part in the battle had undoubtedly turned the tide. Nelson was able to shift the attention of Cordoba away from a unification with Moreno and give the rest of Jervis’ fleet the necessary time to catch up and join in the fight. ]

Cuthbert Collingwood, commanding HMS Excellent, would subsequently play a pivotal role in the next phase of the battle. Collingwood’s devastating broadsides first forced the Sar Ysidro (74) to strike her colours. He then went further up the line to relieve Nelson by positioning himself between HMS Captain and her opponents, the San Nicolas and San José.

Excellent’s cannonballs pierced the hulls of both ships as “… we did not touch sides, but you could put a bodkin between us, so that our shot passed through both ships”. The disconcerted Spanish even collided and became entangled. In this manner Collingwood set the scene for probably the most remarkable episode of the battle: Nelson’s so-called “Patent Bridge for Boarding First Rates”.

As his ship was completely steerless, Nelson realised that she was not suited anymore to confront the Spanish in the normal fashion by means of broadsides. He ordered the Captain to be rammed into the San Nicolas in order to board her. The charismatic commodore led the attack, clambered aboard the enemy ship and cried: “Death or glory!”. He quickly overwhelmed the exhausted Spanish and subsequently made his way into the adjacent San José.

He thus quite literally used one enemy vessel as a bridge to seize another. It was the first time since 1513 that an officer of such a high rank had personally led a boarding party. With this act of gallantry Nelson secured his rightful place in the hearts of his fellow countrymen. Sadly, it has too often overshadowed the valour and contribution of other ships and their leaders such as Collingwood, Troubridge and Saumarez.

Don José De Cordoba finally accepted that he was bested by British seamanship and retreated. The battle was over. Jervis had captured 4 Spanish ships of the line. During the battle some 250 Spanish sailors lost their lives and a further 3,000 were made prisoner of war. More importantly, the Spanish had retreated into Cadiz where Jervis was to blockade them for the coming years, thus providing the Royal Navy with one lesser threat to deal with.

Furthermore, the Battle of Cape St. Vincent had provided Britain with a much needed boost in morale. For their achievements “Old Jarvie” was made Baron Jervis of Meaford and Earl St Vincent, while Nelson was knighted as a member of the Order of the Bath.

Oliver Goossens is a master of history of antiqities at the Catholic University of Louvain, Belgium, currently focusing on Hellenistic political history. His other field of interest is British maritime history.

Published July 21st 2021