The Lord of Misrule was a mischievous character appearing in medieval English celebrations and soon became a ubiquitous element of Christmas festivities, maintaining a strong presence in the royal court for several generations.

The origins of mischief-making to celebrate festivities has roots stretching back to Ancient Rome with the appointment of ‘mock-kings’ in the guise of the Roman deity Saturn, during the winter feast of Saturnalia. In Tudor England, the ‘Lord of Misrule’ was anointed and given the power to lord it over the monarch. Usually a peasant or subdeacon, the Lord of Misrule represented a complete role reversal during times of Christmas revelry, under the premise of celebration, dancing, jesting, feasting and merriment.

Not to be enjoyed exclusively in the royal household, this master of mischief could be found far and wide, whether in a grand country house or a local pub; the aim of the game was to be wild, unruly, and disruptive.

The enjoyment of this Yuletide tradition peaked around the 16th century, but was most exuberantly celebrated in the Tudor period.

Whilst in medieval France, a ‘bean king’ was appointed in the royal household on the 6th January, by the placing of a bean into a cake, the Galette des Rois, and whomever took the slice with the bean would be promoted to ‘king.’ This tradition traversed the English Channel and thus grew in popularity amongst English royalty, featuring in the Christmas celebrations of Edward II and Edward III.

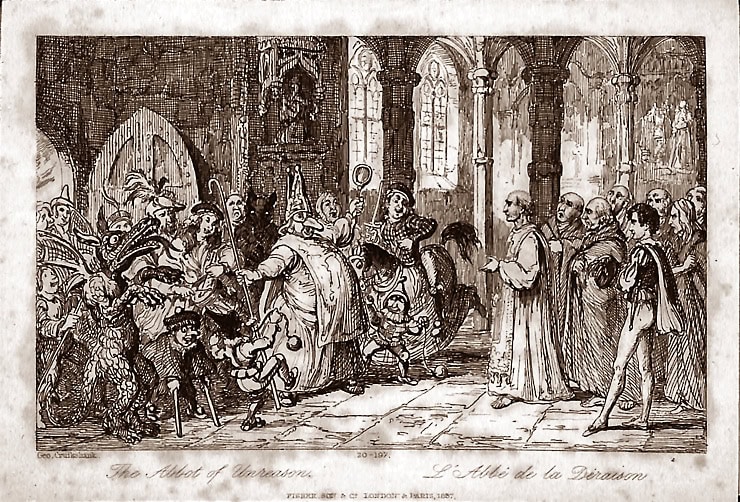

Under the first Tudor monarch, King Henry VII, a revival of the tradition of mischief and role reversal saw a Lord of Misrule as well as an Abbot of Unreason placed at the centre of the Christmas royal revelry every year. The enjoyment of this tradition by the king was clear from the fact that a payment of £5 was issued by the king to the Lord of Misrule. Such a payment was a considerable sum of money and reflected the generosity which these frivolities imbued.

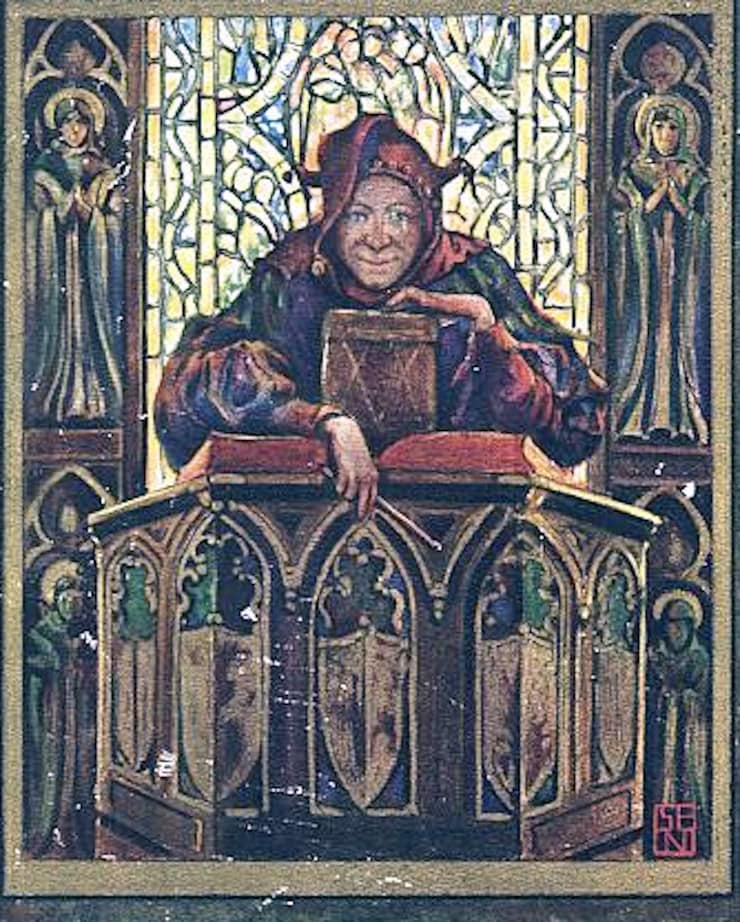

Meanwhile, in the Catholic tradition, ‘boy bishops’ were elected to mark the occasion with a choirboy chosen to assume the duties of a bishop or abbot. Clad in all his regalia, he even led processions and sermons. Some cathedrals, for example Norwich Cathedral, still uphold this tradition today.

The Lord of Misrule was favoured particularly by Tudor monarch Henry VIII, who later in his reign announced a ban on boy bishops.

Whilst he was usually difficult to please, King Henry VIII embraced the celebration of Christmas with no expense spared. With events usually taking place at Greenwich Palace, the invitation was extended to foreign dignitaries who observed the enormity of the festivities, as well as the opulence and grandeur of the feast which saw hundreds of guests attend for several hours at a time.

Henry VIII’s Christmas celebrations consisted of twelve days of pageantry, feasts, dancing and singing, topped off by the Lord of Misrule who orchestrated the more raucous proceedings which followed the formalities. The celebration of Christmas was an important affair for the Tudor monarch and it was expected that the king should be a gracious host, dispensing an unrelenting schedule of conviviality and enjoyment throughout the twelve days of Christmas festivities.

Not one to do things by halves, King Henry VIII lavished his guests with fine dining, drinking and entertainment, opening his royal court for around a thousand people during the entire festive period.

All such merriment was presided over by the Lord of Misrule, the master of ceremonies who orchestrated such boisterous pranks which were described by one commentator as ‘hobby-horses, dragons, and other antics, together with their pipers and thundering drummers to strike up the devil’s dance withal’. This was court-sanctioned madness, where the rule of rank was overshadowed by tomfoolery. In an era of strict social hierarchies and etiquette, the anarchy which ensued took precedence over usual procedure and social standards.

The commands of the Lord of Misrule were given out and directed to all and sundry, the king was no exception.

Will Wynesbury was the first appointed Lord of Misrule during Henry VIII’s reign and was noted to have brazenly demanded money from the king for his services, which was met by a guffaw from the monarch, a reaction few could have expected under normal circumstances.

Henry was a fan of disguise and was known to have appeared at Twelfth Night celebrations in 1510 dressed as Robin Hood.

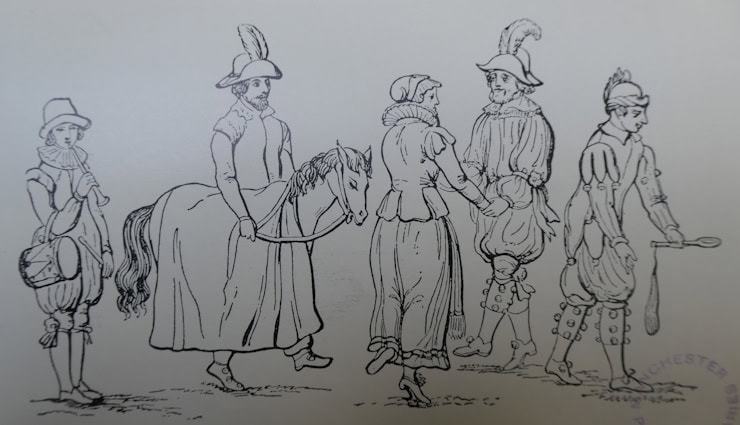

One prominent Lord of Misrule who served during the Tudor period was the courtier and writer George Ferrers, who entertained not only the king but his young son, Prince Edward. He was appointed by the Duke of Northumberland during the Christmas of 1551 with strict orders to entertain the young prince. Accompanied in his task by a company of performers such as jugglers, acrobats, dancers and a fool, Ferrers put on an elaborate show and was paid a considerable sum of money as a result.

When he was not in the royal court, he was busy outside in the streets of London, entertaining vast crowds with his performances including Morris dancers and bagpipers in colourful and impressive spectacles that wowed onlookers in the city.

As a result of his popularity, Ferrers found himself very much in demand and was reappointed in the role of Lord of Misrule in subsequent years up until the reign of Mary I.

Sadly, Ferrers role came to an end and with it, the use of the Lord of Misrule as the new queen passed the organisation of royal Christmas festivities to the Master of Revels and his jaunty and mischievous cousin of misrule made his last appearance in the royal household.

Whilst Queen Elizabeth I was not as taken with the tradition as her father had been, many others in the royal circles were and thus the practise continued in other settings. One example of which occurred in 1561 when royal favourite, Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester attended a Christmas party at the Inner Temple and was anointed as ‘Lord of Misrule’, subsequently presiding over an elaborate revelry of games and dancing, all of which concluded with a hunt taking place within the hallowed halls of the Inn.

Outside royal circles, the appearance of the troublemaking character continued to prevail until the Stuart period when the Lord of Misrule became less ubiquitous. It was the Tudors who truly revelled in these festive shenanigans.

That being said, the character still found occasion to appear, particularly in certain locations and amongst distinct circles such as in public schools and esteemed universities where the students elected a ‘Christmas prince.’

Such celebrations which took place in several Oxbridge colleges often concluded in disorderly behaviour; in some cases, such as in 1628, ending in arrests made by the Lord Mayor himself.

Whilst the Lord of Misrule had reached its pinnacle in the Tudor period, versions of this jovial character appeared in latter centuries such as during the reign of King Charles I and his use of a ‘Prince d’Amour’ for Christmas entertainment.

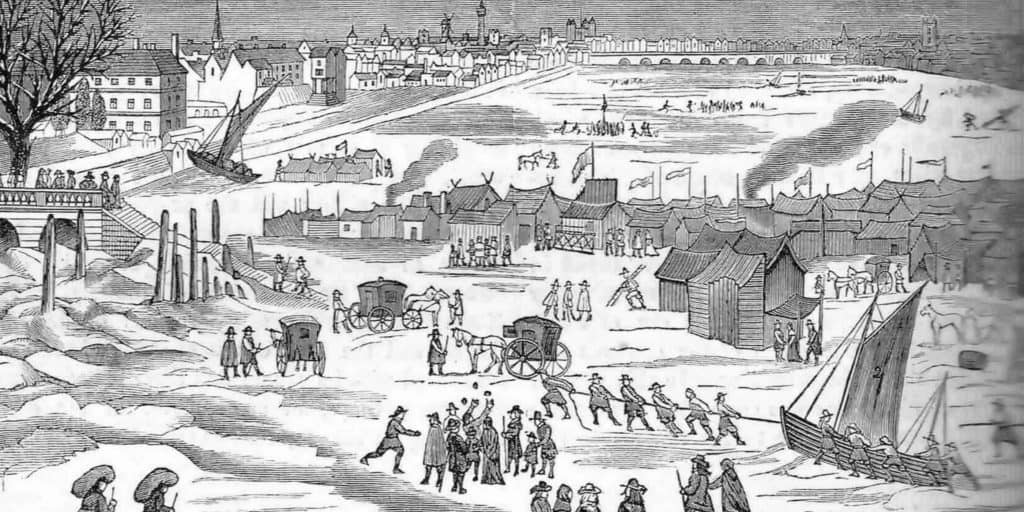

In the 17th century, the rise of Puritanism and the advent of the English Civil War saw the customs of the Lord of Misrule consigned to the history books, as the opulence and extravagance of Christmas celebrations was viewed by many at the time as gluttony and thus Christmas, along with other Christian celebrations, was banned until the Restoration of the monarchy.

During King Charles II reign, the boisterous activities had diminished somewhat amongst royal circles, however the appearance of a ‘bean king’ or ‘queen’ endured within ordinary households celebrating festivities with a Twelfth Night cake.

Meanwhile, at the Inns of Court, the master of mischief continued well into the 18th century despite falling out of favour with the royals. Eventually, the tradition diluted and evolved into a private household parlour game using peas and beans.

In the advent of the Victorian era, the royal family introduced new Christmas traditions whilst others, such as the Lord of Misrule faded into obscurity along with his more outlandish pranks. The festive season came to be associated with Christmas trees, carolling, crackers and Christmas puddings, presenting a more wholesome family image in contrast to the wild days of Tudor celebrations. The days of disguises and disorder had became a thing of the past!

Jessica Brain is a freelance writer specialising in history. Based in Kent and a lover of all things historical.

Published: 9th December 2025