Ireland has its Blarney Stone, which is said to have the power of conferring loquaciousness on those who kiss it; the Scots have the mysterious Stone of Destiny, or Stone of Scone. This stone was considered of such significance that Edward I carried it away to London to become the coronation stone of English monarchs. After much tussling, dispute, and one daring raid, the Stone of Destiny was returned to Scotland. The Scots agreed to lend the Stone to England for coronations as required (accompanied at the border by cries of “haste ye back, mind!”).

It’s interesting that with all the lore surrounding talkative stones and strange stones of destiny, one important stone on the island of Britain is often overlooked. Surprising really, given the English interest in the other two, that their own enigmatic lump of rock, London Stone, rarely gets mentioned.

That’s what it’s known as, not the London Stone, but simply London Stone, immediately imbuing it with an identifiable personality. You feel you could shake hands with a character called London Stone, a cheeky cockney chappie perhaps. London Stone comes across as a pal who would take you on a jolly knees-up tour of the capital, complete with all the cliches: jellied eels, Pearly Kings and Queens, and a pint or two in a Victorian corner house pub with a rattling piano.

In the twenty-first century, London Stone is finally getting some of the recognition it certainly deserves, in literature and the media. However, it can still be overlooked, safely enclosed as it is in a niche at 111 Cannon Street in the City of London. It’s easy for passers-by rushing to work to ignore it, or tourists to miss it on their way to better-known landmarks. Yet that’s exactly what London Stone is, a landmark, and just as worthy as its peers, chatty Blarney and brooding Destiny. Where did it come from, and what’s its story?

Geologically-speaking, London Stone is a block of oolitic limestone, often described as “irregular”, which hales from Rutland, a known-source of stone from Roman times onwards. Rutland limestone was a popular building material in pre-modern times. It measures around 53 × 43 × 30 cm (21 × 17 × 12 inches), but is only a remnant of a much larger stone block that once existed. A chip (albeit a big one) off the old block, you might say. However, its origins are still disputed; some say it’s an example of Bath Stone.

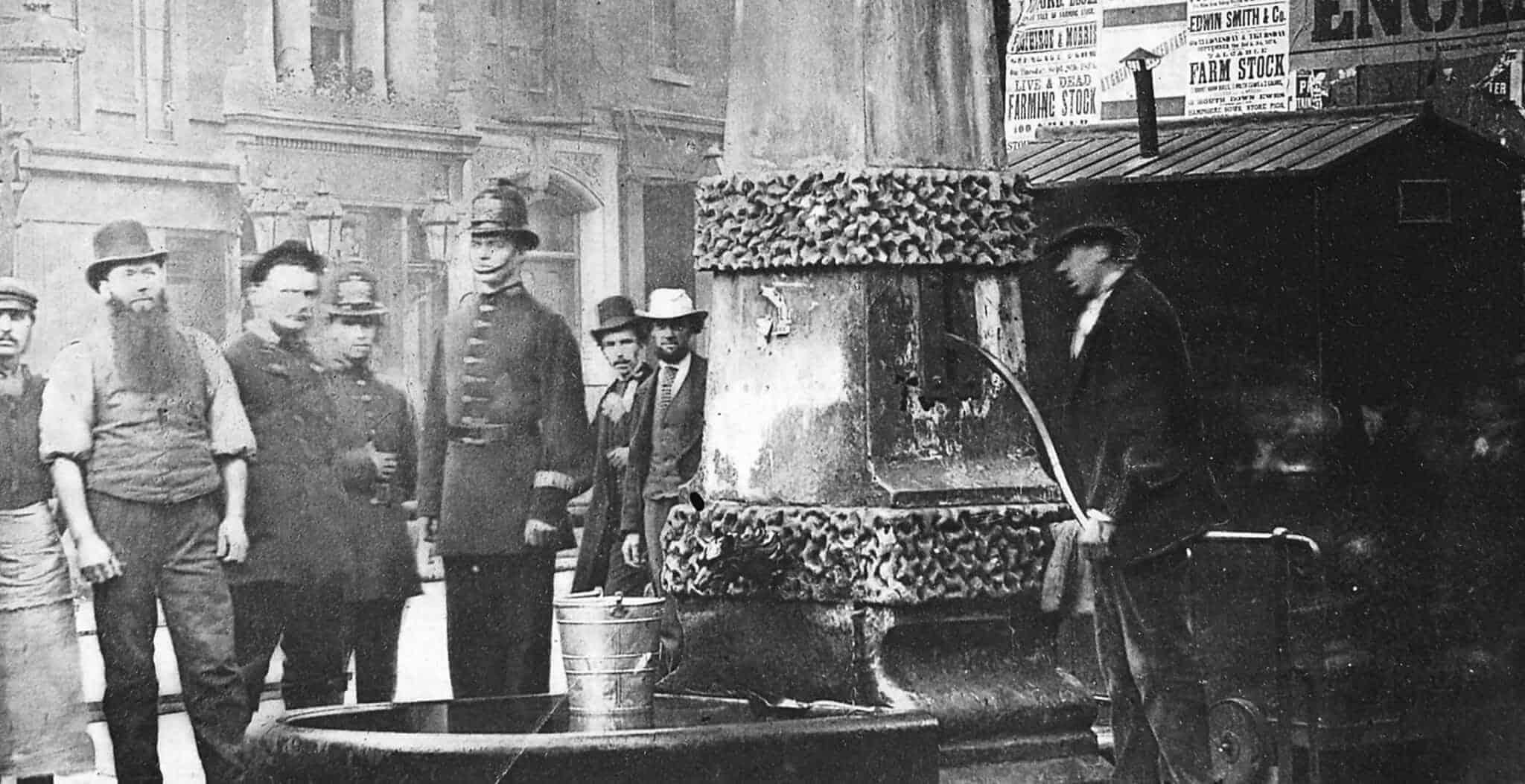

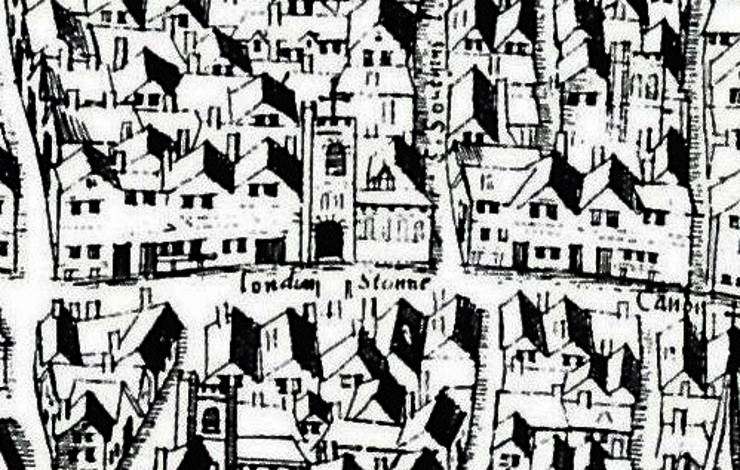

Wherever it came from, London Stone was known from at least 1100 CE. It originally stood on the south side of Candlewick Street, as it was then known, before the creation and widening of Cannon Street. It’s certainly shown on maps of the late sixteenth century.

Obviously it did not escape the attention of the great antiquarian and historian John Stow, who referenced it in his Survey of London in 1598. It was then “a great stone … pitched upright … and fastened with bars of iron”. At three feet high (with more buried underground) it was still not massive, but clearly larger than the contemporary London Stone that remains. It certainly appears to have attracted the attention of visitors to the capital.

The iron bars suggest that local authorities viewed it important enough to ensure it wasn’t appropriated by some villain for building purposes; to avoid it being nicked, in other words. Honestly, grumbled the burghers of London, some of those rascals would have anything if it wasn’t nailed down. What are the police for? What police, replied the city authorities, bemused. You mean the bellmen and constables? Nonetheless, they put “police” on the political agenda to be discussed in a few hundred years or so. In the meantime, a stout iron bar was hard to beat if you wanted to keep something secure.

The other problem was that carters kept crashing into the stone, usually coming off worst in the encounter and littering the street with broken wheels. Canny locals may well have benefitted from this free firewood, sending out their smallest children to distract the drivers with a “Coo, look up there mistah!” just as a cart was rounding the corner and heading towards the stone. On one occasion in 1741, an angry carter and a drayman who’d had a narrow escape from crashing attempted to drag the stone out of the ground, so it was clearly still causing problems and free street theatre for the Georgians.

Stow claimed there was a reference to the stone in a property list of Christ Church Canterbury, now known as magnificent Canterbury Cathedral. This potentially dates London Stone to the eleventh century and a known character who bequeathed property to the Church, Eadwaker æt lundene stane, or Eadwaker at London Stone. A more medieval London name and address it would be hard to imagine, and Eadwaker’s heirs must be fuming at the thought of what the land would be worth today. A few other worthies took the address “at London Stone”, including the first mayor of the City of London, Henry Fitz-Ailwin, in around 1190.

London Stone acquired more lore through its association with Jack Cade, the leader of a rebellion against Henry VI. The story goes that when Cade entered London his first action was to go to London Stone, strike his sword on it, and declare himself “Lord of this city”. The inference was that the stone had some historic, symbolic, or mythological importance for London and the claims of its rulers.

With growing interest in antiquarian matters in the sixteenth century, the stone began to accumulate legend as – well, a stationary rock accumulates moss. Could it be even older than the Saxons, perhaps a Roman landmark? Was it possibly associated with Brutus of Troy, the legendary ancestor of the Britons, King Lud the equally legendary founder of London, or, even deeper in the mists of time, some prehistoric Druid? The answer to all of these is, as so often the case, “we don’t know”.

Lack of evidence didn’t stop people speculating however, and a good move on the part of anyone trying to popularise history is to bring in the Romans, or the Trojans, especially if there isn’t an ancient Egyptian handy. Creating a few legends ensured that London Stone remained a charismatic address until the eighteenth century, and modern archaeological investigations do indicate it may once have formed part of the gateway to a large Roman building.

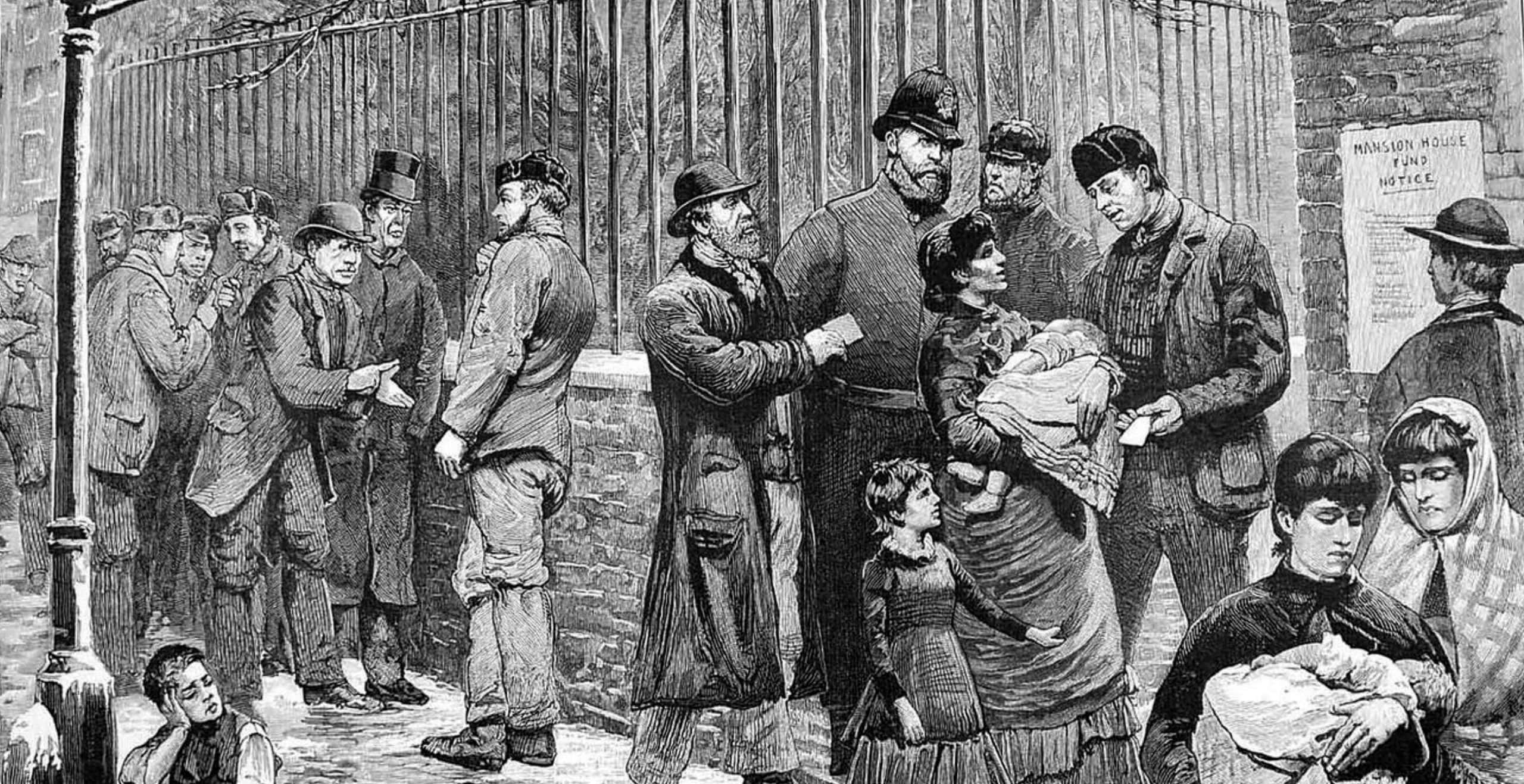

One very prosaic, but potentially more likely use of London Stone was for proclamations and posters. While there is little evidence for the proclamations that may have taken place there (other than Jack Cade’s claim to take the city) there is evidence that notices were posted there in later times. It’s easy to see that it would make sense to use a noted landmark for public notices of all kinds.

A lovely and whimsical publication in about 1522 contained a poem about a marriage between London Stone and the “Bosse of Billingsgate”, which was a water fountain near Billingsgate. London Stone and “the Bosse” are imagined dancing together to celebrate their wedding. Once again it reinforces the importance of London Stone as a landmark, as well as the vital need for good water supplies in the capital.

London Stone has survived long years and has even had a few travels, but like any loyal Londoner, it likes to stay close to its roots. Having survived the Great Fire, London Stone was moved out of the way of Georgian London’s growing traffic to a location next to the door of the Church of St Swithin nearby. It was relocated twice at the church, and set in an alcove in the nineteenth century, when a protective grille was added, and an inscription. London Stone remarkably made it through the Blitz too, even though the church was destroyed so that only the walls remained.

Despite being given Grade II listed status in the 1970s, London Stone occasionally disappeared from the public eye over the next few decades, and also spent some time on display in the Museum of London. It finally went home to Cannon Street in 2018, in a new display.

Given the popularity of the legends of the Blarney Stone and the Stone of Destiny, it is perhaps a little strange that one very obvious, one might say glaringly obvious, legend only seems to have attached itself to London Stone very recently. That is the story of King Arthur drawing the sword from the stone to prove his right to be King of England. There’s no evidence prior to the twenty-first century that this was a tale associated with London Stone. The story of Jack Cade and his sword seems to be a bit of a clue, even though this tale itself is legendary. Nonetheless, London Stone continues to attract lore and myth, whether it is seen as an ancient mystical remnant from the deep past, or simply a place for posting adverts for lost purses. London Stone, like all good story-tellers, likes to keep a few secrets.

Dr Miriam Bibby FSA Scot FRHistS is a historian, Egyptologist and archaeologist with a special interest in equine history. Miriam has worked as a museum curator, university academic, editor and heritage management consultant.

Published: 5th April 2024