In the nineteenth century, the East Enders of London invented a way to communicate through coded speech, which became known as Cockney Rhyming slang.

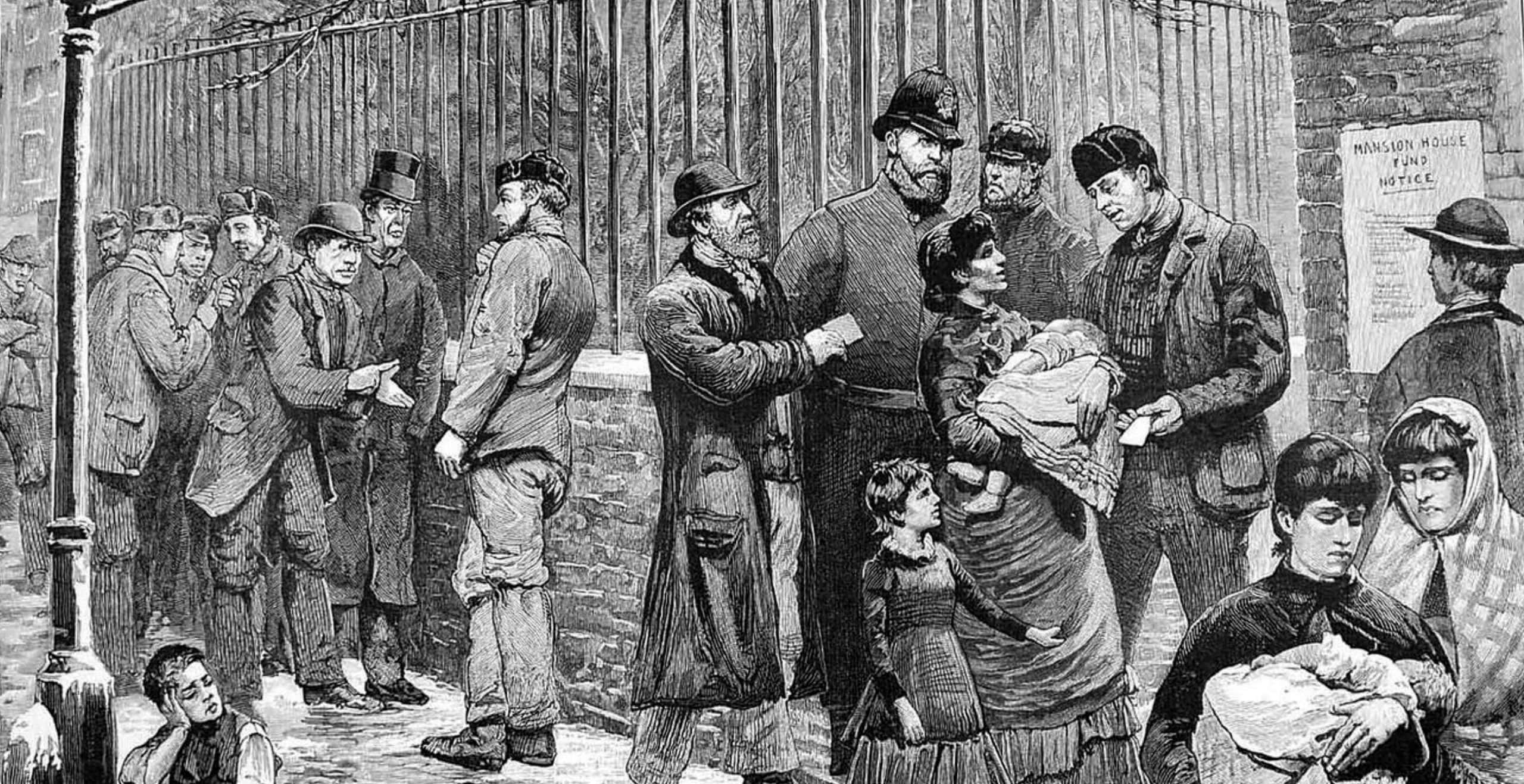

Its emergence has been dated to the 1840s, a time when the East Enders of London were trying to make a living through various means and required a way to communicate so that passers-by, particularly anyone from the police, would not be able to understand what they were saying.

From the market traders to the criminals of London, the East Ender found an ingenious way to elude others from understanding what they were talking about. Since then, the linguistic evolution of Cockney Rhyming slang into the vernacular has provided English speakers throughout the country with many common phrases.

Originating in the East End of London, the term Cockney refers to anyone born within the sound of the church bells of St Mary-le Bow in Cheapside, the City of London.

Within this geographic location in the capital, a Cockney, like other communities around the British Isles already had a dialect with its own unique features, inflections and cadence. Spoken by the working classes, Cockney has become an overarching term used to describe someone from London, particularly with this kind of accent.

The evolution of Cockney Rhyming Slang was however more specific as it emerged out of a necessity to have ones conversation not overheard or understood, often with the effort of concealing illicit activities.

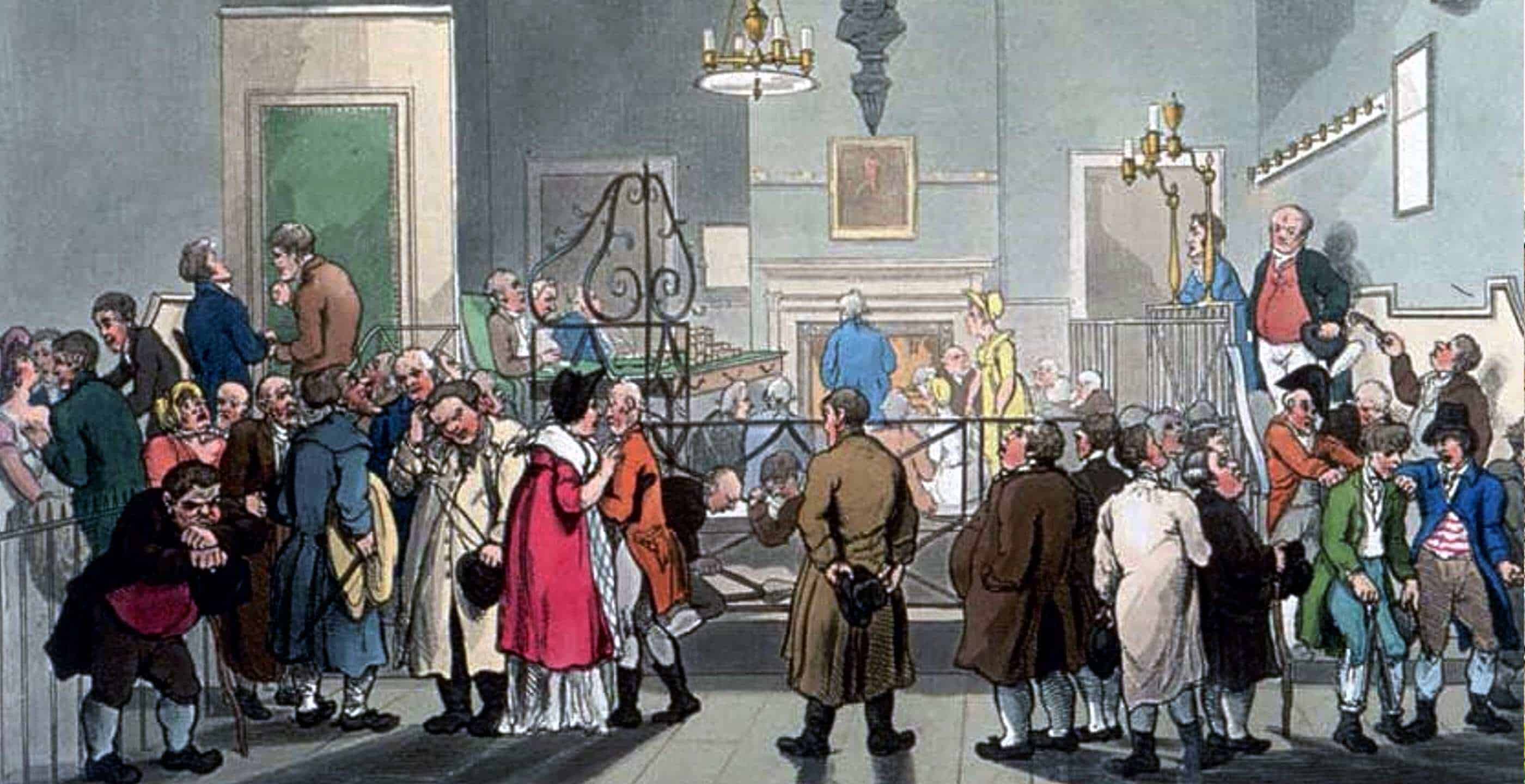

Back in the 1700s, policing the community occurred in a less formal arrangement with individuals paid privately to maintain the law. Without an official governing body for such activities, criminality could take place relatively unchecked. That was until, a London magistrate and author called Henry Fielding put together the first professional police force known as the Bow Street Runners.

The group initially comprised of six paid constables who were trained and paid by the government whilst also receiving rewards when suspects were apprehended.

With the success of the scheme growing, by the early 1800s there were thought to be almost seventy of these constables patrolling the streets of London.

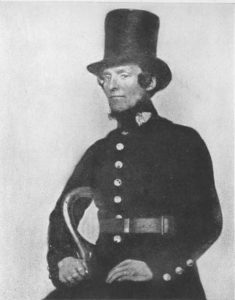

Eventually however, this first foray into formal police forces was replaced by the formation of the Metropolitan Police in 1829 and the eventual disbanding of the Bow Street Runners in 1839.

Whilst London’s population continued to expand, the amount of constables available to manage such a community required a greater response and an even more formal and centralised framework.

Sir Robert Peel who served as Home Secretary in 1822 and later became Prime Minister in 1838, drew attention to these matters whilst numerous parliamentary committees investigated the proposals for law enforcement.

These discussions would lead in time to Peel’s Metropolitan Police Act of 1829 which established the professional, full-time and centralised police force for the Greater London area.

These policeman would become known as “bobbies”, a slang term denoting the connection to Sir Robert (Bobby) Peel which is still used today.

In the mid-1800s, with the new “bobbies on the beat”, patrolling the streets of London, the cockney community were looking for a way to communicate without attracting the attention of the new police force.

The result was an often humorous word play rhyming slang which typically used two nouns with the latter rhyming with the word which was replaced, for example “apple and pears” meaning stairs.

Whilst the slang replacements often rhymed they did not always do so, as sometimes the last rhyming noun was dropped, such as “daisies” meaning boots with the latter half of the phrase missing, “daisy roots”. This simply adds to the confusion for those attempting to grasp the coded language.

In time, the development of these catchy phrases would spread throughout the community, used frequently amongst the criminals of London who were seeking a way to communicate their clandestine activities right under the noses of law enforcement.

It would quickly become an entrenched part of Cockney parlance with dockworkers, fishmongers and market workers all using the phrases.

Some well-known examples include:

Adam and Eve – Believe (Used in the phrase ‘would you Adam and Eve it?)

Apples and pears – Stairs

Cream Crackered – Knackered

Dog and Bone – Phone

Tea Leaf – Thief

Dicky Bird – Word

Lemon Squeezy – Easy

Army and Navy – Gravy

Brown bread – Dead

Ones and twos – Shoes

Duck and Dive – Skive

Baker’s Dozen – Cousin

Jam tart – Heart

Bread and Honey – Money

These phrases would continue to evolve as more people used them and the codified language was adopted into the vernacular of everyday London speech on the streets.

Such phrases also continued to be added to the rhyming slang dictionary with specific links to the activities undertaken by Cockneys at this time in England.

It was quite common in the nineteenth century for Londoners to travel down to Kent and spend their summers hop picking. It was here that the slang term for dog became “cherry” which had its roots in “cherry hog” referring to the container that was used to collect the crop.

The dialect also often included specific areas and place names in London for example:

Hampstead Heath meaning teeth.

Peckham Rye meaning tie.

Tilbury Docks meaning socks.

Barnet fair meaning hair.

From its origins in the mid-1800s, Cockney Rhyming slang had evolved to become an extensive linguistic phenomenon in its own right. With phrases continually added and modified over the decades, what had started with a design to evade the authorities with deceitful criminal overtones had evolved to become often harmless everyday speech used by many individuals.

This evolution would continue well into the twentieth century with original inventions adapted, for example Mickey Bliss meaning ‘taking the piss’ (ridiculing someone) became ‘taking the mickey’. Or ‘telling porkies’ which would commonly refer to someone telling lies, originating from ‘porky pies’.

New words and phrases would be added with references to contemporary culture such as Hank Marvin meaning starving and Basil Fawlty, a popular comedy figure, meaning Balti.

Many of these phrases and references would enter into people’s vocabulary with very little thought into their origins back in the nineteenth century East End of London. One such example is the widely used phrase, still common today, “blowing a raspberry” which originates from ‘raspberry tart’, rhyming slang meaning ‘fart’.

Whilst Cockney rhyming slang became embedded in the lexicon of the English language, it was by no means the only slang of its kind as across the English speaking world, phrases and slang construction evolved for similar reasons in the United States as well as Australia.

By the late twentieth century, increased popularity of certain phrases emerged from its inclusion in television series, films and even music, showing its acceptance into the mainstream of culture and communication.

Now in the twenty-first century, the English language continues to change and adapt, with its ever changing needs and diversity of population. Much like the Cockneys of nineteenth century London, modern English speakers continue to adapt the language for its own use, constantly acquiring new phrases and terminology to reflect a new generation.

Whilst the result of this might mean a decline in some of the slang phrases from the past, many expressions have become a mainstay of the English language often passing our lips without a second thought to their origin.

Cockney Rhyming slang will continue to feature in linguistic constructions, serving as a little piece of history, a reminder that our language and speech, like all aspects of our culture, reflects a complex, diverse and interesting history of people and places which continues to grow and change.

Jessica Brain is a freelance writer specialising in history. Based in Kent and a lover of all things historical.

Published: 10th November 2021