There’s a bit of a mystery about the beard tax imposed by Henry VIII, and it’s not just the mystery of why the heck anyone would want to put a tax on facial hair. After all, there have been many instances of odd taxes. It’s all part of the tax-collectors’ ongoing efforts to squeeze an extra groat or two out of the populace, and they can’t be accused of lack of imagination in that department.

Over the centuries there have, for example, been taxes on windows, wallpaper, hearths, salt and, in ancient Rome, urine. At certain points in history it’s been impossible to light yourself to bed with a candle in the house you built of bricks without paying a tax or two.

The real mystery of Henry’s beard tax though, is whether it actually existed. Henry VIII has always been a rich source of material for urban legends – consider the early 20th century music hall song with the lines “I’m ‘Enery the eighth I h’am, ‘Enery the eighth I h’am, I h’am, I got married to the widder next door, she’s been married seven times before, and every one was an ‘Enery, wouldn’t have a Willie or a Sam…”

Our ‘Enery VIII, the genuine article, now stands accused of introducing a beard tax in 1535. Although the evidence for it is more scant than an actor’s day-old stubble under a celebrity barber’s razor, the idea of it is so appealing that it regularly turns up on various internet sites.

The fact that he’s still the source of urban legends in the 21st century would doubtless have pleased Henry’s ego. However, the National Archives claims no knowledge of such a tax. Perhaps the logistics of collecting it proved just too ticklish a problem.

What we do know is that beards were indeed a touchy business. Drake spoke of his expedition to Cadiz as “singeing the King of Spain’s beard” and Shakespeare’s King Lear includes the lines “By the kind gods, ‘tis most ignobly done/To pluck me by the beard”.

Apart from including one of the most ribald references to beards ever, Chaucer contains many descriptions of male facial hair, or the lack of it. From the daisy-white beard of the Franklin to the foxy red beard of the rambunctious miller with the wart on his nose, beards were indicative of both social status and character.

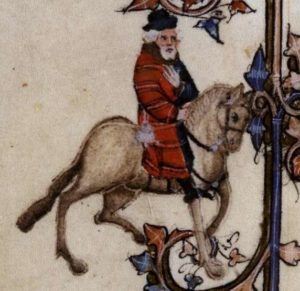

The Franklin from the Ellesmere manuscript of Chaucer’s ‘Canterbury Tales’.

The Franklin from the Ellesmere manuscript of Chaucer’s ‘Canterbury Tales’.

The term “making one’s beard”, which Chaucer used to imply trickery, might have arisen from that vulnerable moment when the barber takes control of his client’s beard in order to dress, or trim it. It’s not hard to see how having a man with a cut-throat razor (the clue’s in the name) shaving off one’s facial hair requires a moment of absolute trust between barber and client. Complicating it with the comment “The price of the Barbarossa lather ‘n trim doesn’t include tax, sir,” at a critical moment is just asking for trouble.

Since it has been argued the alleged tax was graduated, so that people paid more according to wealth and status, it’s possible that the concept of a beard tax has become conflated with genuine Tudor legislation. The so-called Sumptuary Laws are well-documented.

The primary purpose of the Sumptuary Statutes was to maintain the social hierarchy, with strict regulations regarding who was permitted to wear various materials, styles of clothing, and even colours. However, many of the cast-off garments of the elite ended up in second-hand clothing shops or in the hands of worthy servants, and so in reality there would appear to have been some flexibility around the operation of the laws.

Allegedly, Henry VIII’s daughter Elizabeth I (clearly a chip off the old block, to create an unhappy analogy) was responsible for the introduction of her own version of the beard tax. In an anecdotal version of events, the tax was payable on all beard growth over two weeks. Knowing Elizabeth’s sense of humour when it came to her courtiers, it’s possible that the ingenious ways they met the requirements of her law resulted in a lot of royal cackling.

The beard tax imposed by Peter the Great, on the other hand, is well-documented. Instituted after he had spent time in Europe observing naval ship-building techniques, it appears to have been one of the modernising ideas he brought back with him to Russia.

Whether or not he discovered and admired the fashion for clean-shaven faces among the late 17th century English elite while he was in London, where he visited the Royal Navy dockyard and attended Parliament, isn’t clear. However, he was sufficiently enthusiastic about the idea to grab a razor himself and put his reforms into action on any innocent who had just troika’d in from the wastes of Siberia sporting a fine growth of beard.

Russian beard token from 1705 to prove that the owner had paid Peter The Great’s beard tax

Russian beard token from 1705 to prove that the owner had paid Peter The Great’s beard tax

Eventually tiring of the principle “if you want a job doing well, you have to do it yourself”, Peter realised that imposing a beard tax would both deal with recidivist beardies while also filling the imperial coffers. In a stroke of warped genius, he issued tokens showing a stylised face with a neatly-trimmed beard to those who’d paid the tax. Oh, the irony!

Published: March 18th, 2019.