To call Dr Robert Hooke a genius is too small a word to describe such a man. Robert Hooke was born on the Isle of Wight on 28th July 1635. As a child he was sickly, which kept him away from school for long periods. His mind, therefore, remained largely uncluttered by any preconceived learnings and as such, flourished.

Robert loved to draw, and from his sick bed armed with a drawing pad and pencil his imagination was let loose. His time away from school was well spent and he began to draw incredibly detailed diagrams. His father, a clergyman, was so taken by his artwork, especially those for new clock mechanisms that he declared them no less than the work of a genius.

Robert’s father died in 1648, bequeathing £40 to Robert in his will, a substantial sum in the 17th century. Now into his early teens, Robert set his sights on the Westminster School in London, where he excelled in languages, mathematics and mechanics.

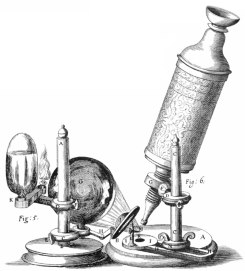

1653: At eighteen he became a student at Christ Church College. He focused his attention on science, built telescopes and observed the orbit of Mars and the gas giant Jupiter. He studied fossils and began delving into the world of evolution. Not satisfied with the instruments of that time, Robert went on to invent the modern microscope.

Hooke’s microscope, from an engraving in ‘Micrographia’.

Hooke’s microscope, from an engraving in ‘Micrographia’.

1662: At the grand old age of 27, Hooke was bestowed with the grand title of Curator of Experiments for the Royal Society.

1665: Hooke was an astronomer, but at some point decided to turn his attention to our own world, in particular our invisible world. His observations of slices of cork bark under his microscope revealed that they were made up of tiny square segments, which he called ‘cells’ as the minuscule square structures that he observed were said to have reminded him of monks cloisters.

He became thoroughly engrossed in the world of the invisible. Following his discoveries, he wrote and illustrated what must be one of the greatest books of all time: Micrographia. The incredibly detailed drawings of insects are simply astonishing and surely will never be bettered. The book took the world by storm. Hooke’s invisible world was now made visible for the first time for all to see.

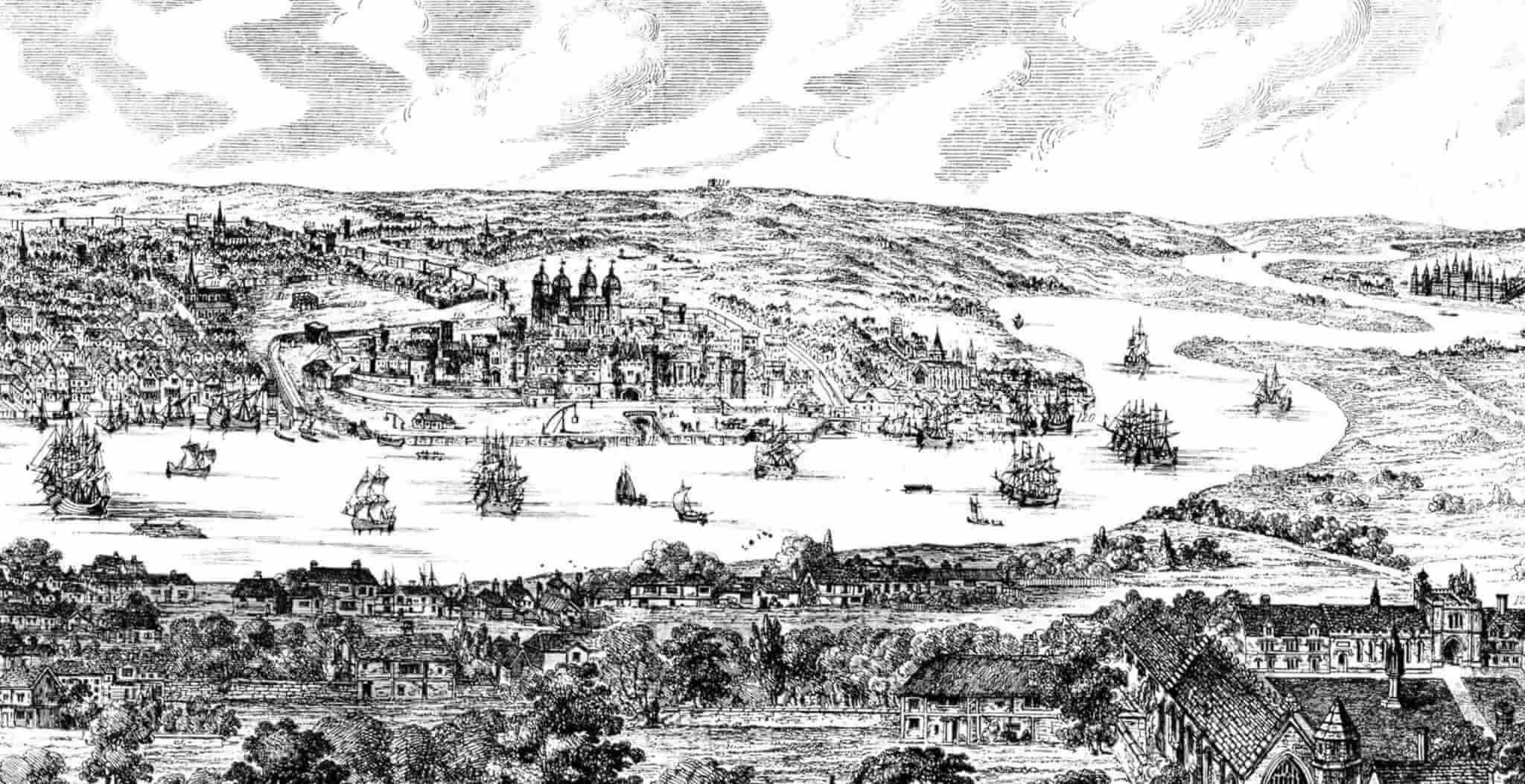

1666: The Great Fire of London is said to have begun in a bakery in Pudding Lane, however through modern investigatory techniques, it is now thought it may have started elsewhere. The Great Fire destroyed 87 churches and 13,200 houses. However, the fire did London a great favour and destroyed many of the rat infested slums and festering tributaries of sewage, cleansing the streets. And out of the smouldering ash, the greatest city on earth was born.

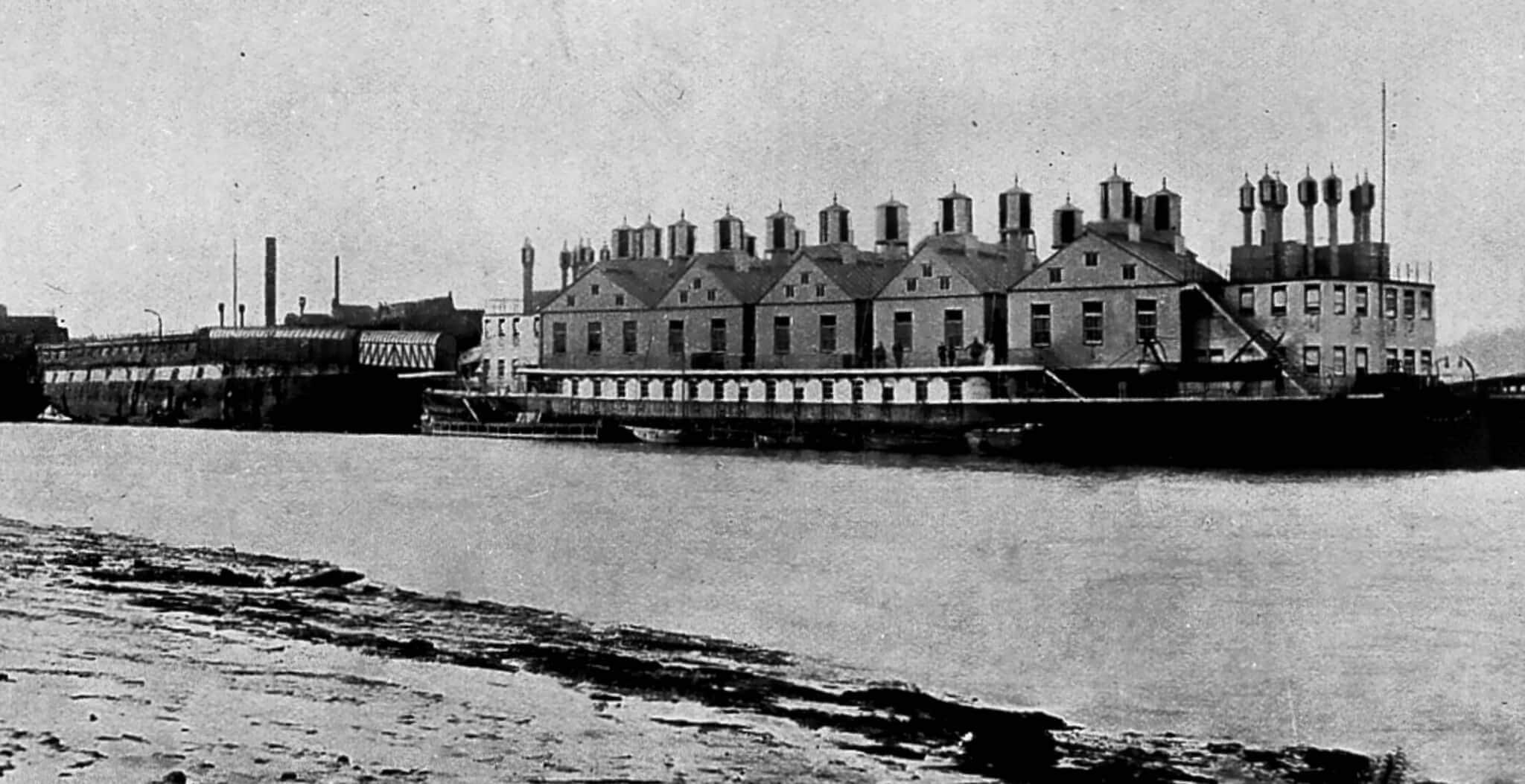

Building work on a monument commemorating The Great Fire of London began in 1671 and was completed in 1677. The 202ft high column is still the tallest freestanding stone column in the world, and was designed by Sir Christopher Wren and Robert Hooke, who had now turned his hand to architecture. The monument served a dual purpose: Hooke used it as a gigantic telescope, with an underground laboratory where he performed scientific experiments. Whilst many of his other experiments were extremely successful, unfortunately the vibrations from the heavy London traffic ended Hooke’s dream of using the monument as a giant telescope.

When paying a visit to this extraordinary building, please spare a thought for the genius who put it there: Robert Hooke. (1635-1703)

The Monument, Monument Street, London EC3R 8AH

Public transport: Monument and Bank are the closest tube stations, London Bridge, Cannon Street and Fenchurch Street are the closest train stations.

Paul Michael Ennis is a freelance journalist who also writes crime thrillers under the name Bill Carson.

Published: 29th March 2015