Britain loves potatoes. And it’s not just me saying that, there are numbers to back that up! The average Brit eats over 100 kilos of spuds in various forms every year. But that hasn’t always been the case. Potatoes had a humble beginning, high up in the Andes, thousands of miles from Britain’s shores.

The Origins of the Humble Potato

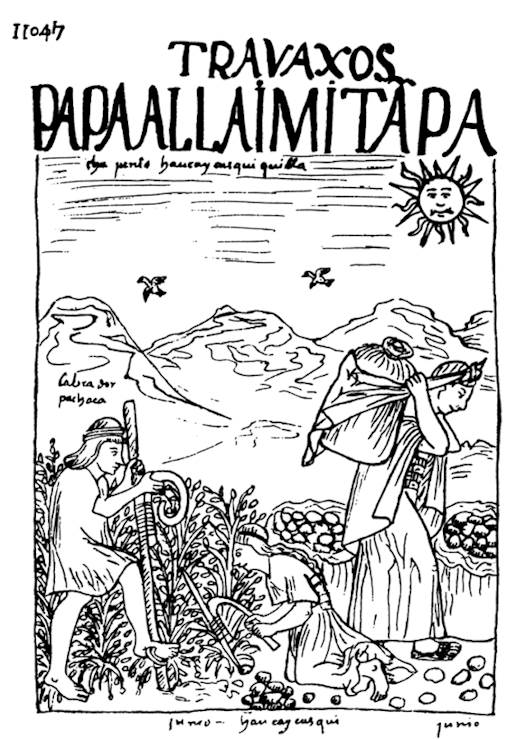

While we can never know the exact date potatoes were first harvested, scientists have been able to narrow it down. By examining microscope remains of potatoes discovered in the mountains of southern Peru, researchers have discovered that ancient Peruvians began cultivating this tuber at least as far back as 3400 BC.

The culture that first produced this wonder food lived at a site that is now called Jiskairumoko. Near Lake Titicaca, this society flourished from 3400 BC until 1600 BC. While potatoes may have been their most important contribution to later history, archaeologists have also found evidence for the earliest gold working in the Americas at this site. The residents of Jiskairumoko were true innovators.

When the potato first emerged in the Andean highlands, it wasn’t exactly what we think of today when we imagine popping a potato into the oven. In fact, the earliest spuds would have been no larger than your thumbnail!. In a process similar to the cultivation of corn further north in Mesoamerica, ancient Andeans slowly selected the larger tubers for their size, replanting the ones that would yield the best harvest. Over the millenia, this resulted in potatoes the size of a person’s hand. Take that Gregor Mendel!

Potatoes Come to Britain (Somehow)

Okay, back to Britain.

By the time the British arrived in the Americas, the potato had become a staple for indigenous cultures far beyond the Andes. Spanish conquistadors were the first Europeans to encounter the food when they landed in the Caribbean, where the Arrowak and Taíno peoples called them batatas. As Europeans played a game of telephone with indigenous words for flora and fauna that did not exist back home, batatas eventually made its way into the English lexicon as “potato”.

It seems that potatoes first made their way to the British Isles by way of Bosque fisherman. Given that their homeland straddled the line between the kingdoms of France and Spain, two of the major players in European colonialism during the 16th-century, the Bosque frequently plied the waters of North America. One their way home, many Bosque ships would stop on the west coast of Ireland, where they most likely introduced the local Irish population to the new found tuber. While potatoes would not become big on the Emerald Isle until after the Cromwellian Wars, the seed, so to speak, was planted.

Across the Irish Sea, it’s less clear who first introduced the potato to English shores. Recent research by historians indicates that Spanish merchants introduced potatoes to eager Anglo audiences during the 1570s. About a decade later, Sir Francis Drake brought the potato home to England after his epic journey around the world. Most likely introduced to the tuber plant by the colonists he rescued from the failed Roanoke colony in Virginia, English authors began calling the plant the “Virginia potato” after Drake’s voyage.

A Mixed Reception Across the Realm

No matter how potatoes came to Britain, their reception was mixed.

Adoption among the lower socio-economic classes seems to have occurred fairly quickly. Potatoes proved extremely adaptable to England’s climate and varying soil conditions. This was especially true in the northeastern area of the kingdom, where the soil is dominated by sand and clay. Capable of growing in conditions less than ideal for large scale agriculture, potatoes quickly became a staple among the peasant classes of the northeast.

The herball or Generall historie of plantes, the first publication in England to discuss potatoes, gives us a clue as to how these early potato farmers may have used the crop:

They [potatoes] are used to be eaten ro[a]sted in the ashes. Some when they be so ro[a]sted infuse them and sop them in Wine; and others to give them the greater grace in eating, doe boyle them with prunes, and so eate them. And likewise others dresse them (being first ro[a]sted) with Oyle, Vineger, and salt, everie man according to his owne taste and liking. Notwithstanding howsoever they bee dressed, they comfort, nourish, and strengthen the body, procuring bodily lust, and that with greedinesse.

The potato’s popularity among the lower classes, however, brought derision upon this versatile tuber from England’s nobility. In a Malthusian turn of logic, commentators among the upper-crust noted that the potato was, in one scholar’s words, “excessively nourishing and so facilitated laziness.”

Later, in the eighteenth-century, some in Britain began to equate the spread of the potato in Europe with the spread of Catholicism. Recognizing the potato’s popularity in Catholic-dominated areas like Ireland, France, and Spain – and wishing to use anti-Catholic sentiment to their own advantage – those running for office in 1765 coined the slogan “No Potatoes, No Popery!”

Fortunately for all the lovers of chips, sentiments have since changed.

Jordan Baker holds a BA and MA in History from North Carolina State University. A lover of all things historical, he concentrates his research and writing on the history of the Atlantic World. He also blogs about history at eastindiabloggingco.com.

Published: 2nd August 2024