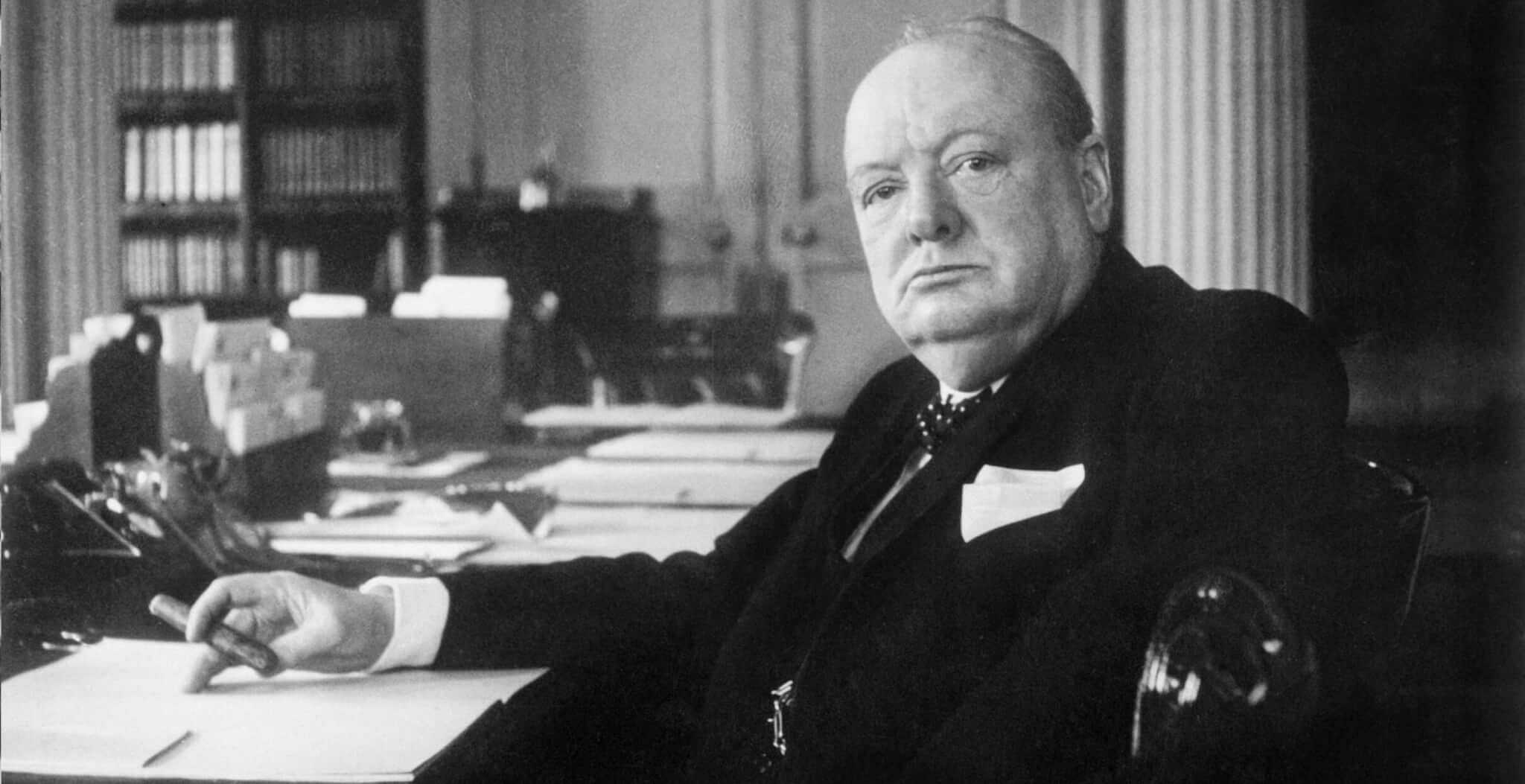

BRITAIN faced two great threats in the early stages of World War Two – bombs and starvation. Courage and unbending spirit helped the nation to survive the Blitz, one man’s superb business efficiency stemmed the pangs of hunger.

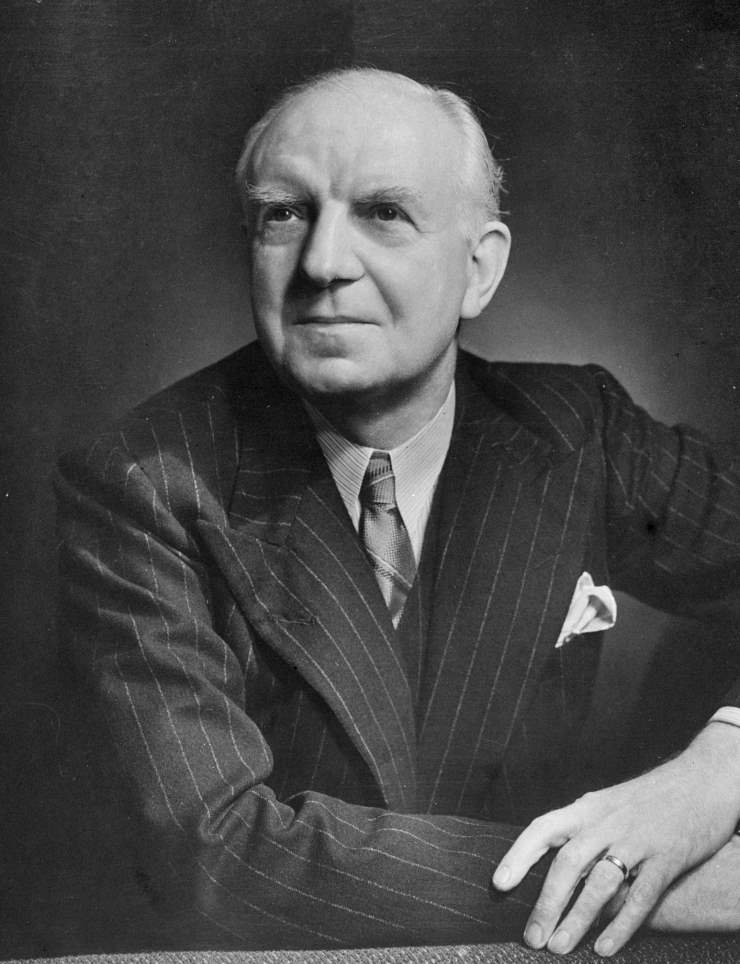

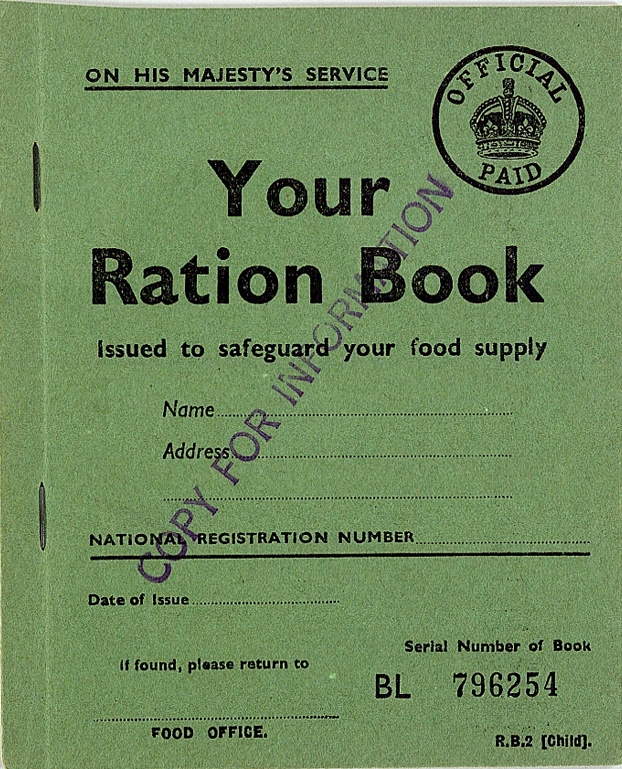

Lord Woolton, the Minister for Food, was determined that Britain’s larder remained well-stocked, and that, despite rationing and poverty, everyone had something to put on the table. “We must all be fighting fit,” he declared.

Yet, through the hellish winter of 1940-41 when the bombs rained down on major cities and ports, Britain was perilously close to running out of grub. Traditionally, two thirds of its food was imported but the war had devastated supply routes. And even when ships did survive the Atlantic crossing, there were difficulties unloading their cargoes because of bomb damage.

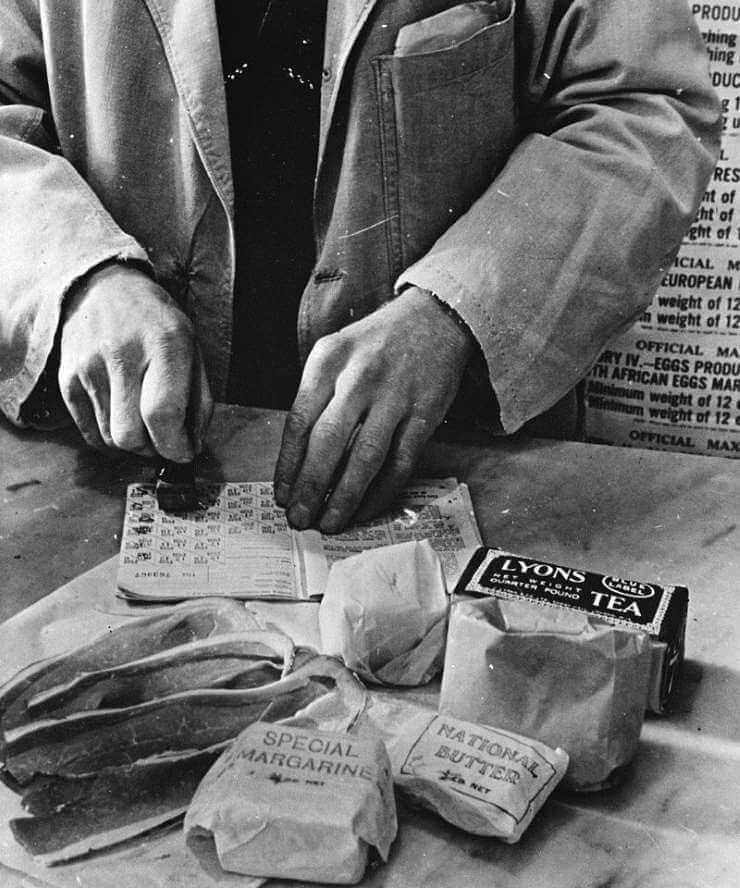

Woolton, a scientist turned businessman turned civil servant, launched the National Food Campaign, urging people to make weaker tea – ‘one for you, one for me and none for the pot’ saved 50 shiploads of tea per annum – and never to peel potatoes. Betty Driver, the singer who became the Coronation Street character Betty Turpin, regaled radio audiences with a popular ditty:

‘Those who have the will to win

Cook potatoes in their skin

Knowing that the sight of peelings

Deeply hurts Lord Woolton’s feelings’

Formerly chairman of the John Lewis company, Woolton was a superb team leader and quickly had the Ministry for Food working at full capacity, particularly on propaganda. Soon Britain was awash with posters proclaiming: ‘Waste Not, Want Not’, ‘Grow Your Own’, and ‘Eat Up Your Greens’. Brief adverts, known as food flashes, popped up on cinema screens, and cartoon characters like ‘Doctor Carrot’ and ‘Potato Pete’ appeared in newspaper and magazines.

He even promoted a story that eating carrots improved the sight of Britain’s successful night-time fighter pilots.

Perhaps the most influential marketing ploy was a radio programme, broadcast six days a week after the morning news, aimed primarily at housewives and entitled ‘The Kitchen Front’, in which well-known cooks offered advice and cheap but sustaining recipes. One was ‘Woolton Pie’, a veg mixture thickened with oatmeal and topped with pastry.

With meat and eggs severely rationed and citrus fruits only rarely available, Woolton was aware that people needed more than veg. Children and the poor were particularly vulnerable. His solution was free school meals and milk for 650,000 youngsters and the ‘British Restaurant’- a nation-wide scheme of basic cafes, often run by volunteers, offering cheap, nutritious meals. For eight pennies, you could tuck into a plate of meat and veg, with bread, and a pudding.

Woolton, who was born Frederick Marquis and brought up in the terraced streets of Salford and Manchester, had a natural affinity with the working class and, after graduating from Manchester University, he lived in an impoverished district of Liverpool carrying out social work.

One day a woman neighbour was found dead in her home – she had starved to death. The tragedy informed Woolton for the rest of his life.

When he moved into business and, later, into the highest ranks of the Civil Service, he also dealt easily with the nation’s wheelers and dealers, major industrialists and top politicians. By the time he was drafted into the war-time effort, he had a deep knowledge of how Britain worked.

Despite that, his initiatives would not have succeeded had he lacked communication skills and charisma. The tall grey-haired Woolton, impeccably dressed, stood out in any company. He talked easily and persuasively, both in War Cabinet conferences and on the radio, where he made countless broadcasts and became affectionately known to listeners as ‘Uncle Fred’.

Of his few critics, Winston Churchill was one, especially when Woolton organised a lunch for him and the new USA Ambassador. The venue was London’s Savoy Hotel where the chef was usually tasked with producing an exotic recipe like crayfish with foie gras but, on this occasion, had been ordered to put a Woolton Pie on the table. The surprised and disgruntled Prime Minister demanded a plate of cold beef instead, and, afterwards, complained bitterly, only for Woolton to stand his ground, insisting that rich and poor had to tighten their belts.

Gradually Churchill was won over and Woolton was given his head. He limited restaurant meals to three courses with a maximum price of five shillings, introduced the National Loaf (a nutritious but unpopular wholemeal bread) and threatened anyone who wasted food with a possible two years prison term or £500 fine, a measure aimed at the profiteers rather than ordinary households. And powdered milk was made available to some of the country’s key workers – vermin hunting cats used to protect food stacked in warehouses.

Thankfully, from May 1941 the USA shipped over cargoes of eggs, flour, cheese, lard, and canned milk. But without ‘Uncle Fred’s’ pie – a blend of organisation and efficiency under a thick crust of ingenuity – Britain would have struggled to survive.

Woolton went on to become Minister of Reconstruction, planning for Britain’s future after the war, and Chairman of the Conservative Party 1946-55. He died in 1964.

Colin Evans is a retired journalist

Published: 20th September 2022.