On September 3rd 1939, British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain took to the airwaves to announce Great Britain was officially at war with Germany. Saying the government had done all it could to avoid conflict, he emphasized the people’s responsibility to the war effort. “The Government (has) made plans under which it will be possible to carry on the work of the nation in the days of stress and strain that may be ahead. But these plans need your help,” he said. The men of the United Kingdom answered the call, and so did the women. Women did not take up arms; they took up shovels and axes.

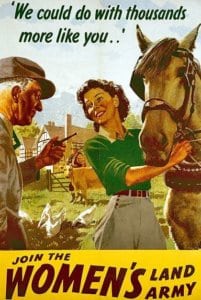

The Women’s Land Army (WLA) was first organized during World War I to fill the agricultural jobs left open when the men left for war. By allowing women to step into the roles traditionally limited to men, the nation could continue to feed its people at home and abroad. The WLA was reinstated in 1939 as the country prepared for another war with Germany. Encouraging women single women between the ages of 17½ and 25 to volunteer (and later bolstering their ranks through conscription), there were over 80,000 ‘Land Girls’ by 1944.

Keeping the nation fed remained the WLA’s primary mission, but the Ministry of Supply knew agriculture was also critical to military success. The armed forces needed lumber to build ships and aircraft, erect fences and telegraph poles, and produce the charcoal used in explosives and gas mask filters. The MoS created the Women’s Timber Corps (WTC), a subset of the Women’s Land Army, in 1942. Between 1942 and 1946 over 8,500 “Lumber Jills” throughout England, Scotland, and Wales cut down trees and worked in sawmills, ensuring the British army had the lumber it needed to keep its men at sea, in the air, and safe from Axis chemical weapons.

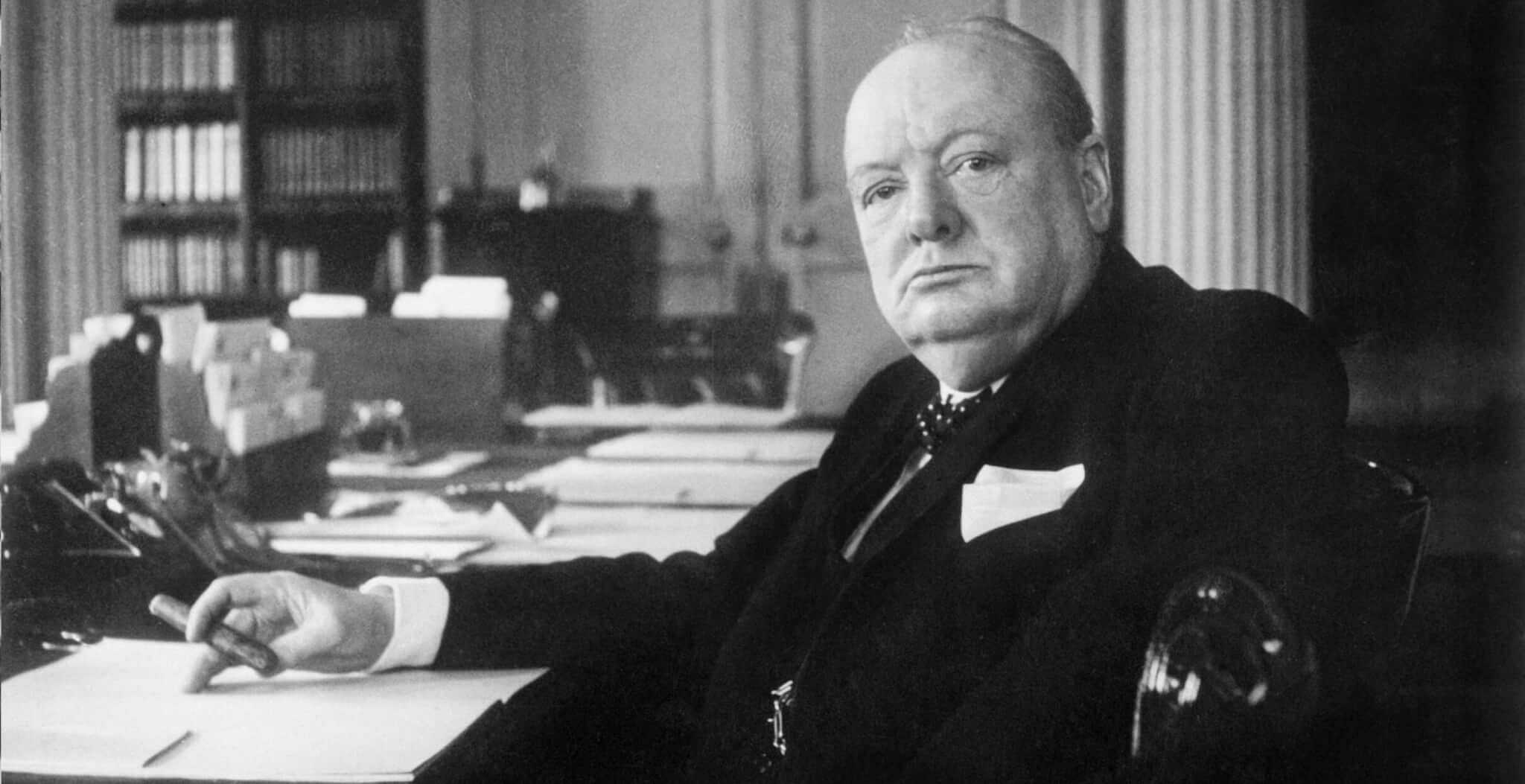

Whilst each groups’ uniform included riding trousers, boots and dungarees, the WLA and WTC uniforms differed in headwear and badge emblem. The WLA’s felt hat was emblazoned with a sheaf of wheat, while the badge device on the Women’s Timber Corps’ wool beret was fittingly a tree. The idea of allowing women to wear trousers as part of a government-sanctioned uniform had shocked many during WWI, but the necessities of war required a certain softening of gender expectations. The Empire needed the help and support of every citizen, man or woman, to win the war. As Winston Churchill had reminded the House of Commons in 1916, “It’s no use saying, ‘We are doing our best.’ You have got to succeed in doing what is necessary.” The WLA and WTC were up for the challenge. “That’s why we’re going to win the war,” explained Women’s Timber Corps veteran Rosalind Elder. “Women in Britain will do this job willingly!”

The Land Girls and Lumber Jills successfully filled roles long considered unsuitable for women, but pre-war stereotypes persisted. Some male workers “didn’t like us maybe because we were female…the old Scottish attitude to women: they can’t do men’s work, but we did!” said WTC veteran Grace Armit in Jeanette Reid’s ‘Women Warriors of WWII’.

In addition to shaking social gender norms, the Land Girls and Lumber Jills unofficially influenced post-war relations with wartime enemies. The government urged the women not to fraternize with the enemy German and Italian prisoners of war they worked alongside, but first-hand experience with the POWs lent them to a different view. “If we are to have a proper peace after the war, we shall have to show consideration and kindness to every country, even if they are our enemies,” wrote one service member in a May 1943 letter to the WLA publication The Farm Girl. “There is no need to be overfriendly, but let us at least show the true British spirit of courtesy and goodwill.” This spirit of goodwill and respect was an example for all citizens.

The Women’s Timber Corps demobilized in 1946, with the Women’s Land Army following in 1949. Following their release from service, most WLA and WTC members returned to the lives and livelihoods they enjoyed before the war. Society also returned to the pre-war distinctions regarding what women could and could not do. As a result, the WLA and WTC soon became no more than footnotes in the history of the war. “The war came on and you had to do your bit,” said Ina Brash. “We didn’t get any recognition, pensions or anything like that. Nobody knew anything about us.”

Official recognition took over 60 years. On October 10th 2006, a memorial plaque and bronze statue honouring the WTC was erected in Queen Elizabeth Forest Park in Aberfoyle. Eight years later, a memorial honouring both the WLA and WTC was erected in the National Memorial Arboretum in Staffordshire. These memorials, and the women’s stories recorded in interviews and memoirs, remind us it was not only men who answered the call to serve their nation and preserve freedom. Women were also called, and answered they did.

Kate Murphy Schaefer holds an MA in History with a Military History concentration from Southern New Hampshire University. Her research centers on women in war and revolution. She is also the author of a woman’s history blog, www.fragilelikeabomb.com. She lives outside Richmond, Virginia with her wonderful husband and spunky beagle.