A white feather has always had symbolism and significance, often with positive spiritual connotations; however in Britain in 1914, this was not the case. With the outbreak of the First World War, the Order of the White Feather was founded as a propaganda campaign to shame men into signing up to join the fight, thus associating the white feather with cowardice and dereliction of duty.

The symbol of the white feather in this context was thought to have derived from the history of cockfighting, when a white tail feather of a rooster meant that the bird was considered inferior for breeding and lacked aggression.

Moreover, this imagery would enter the cultural and social sphere when it was used in a novel of 1902 entitled, “The Four Feathers”, written by A.E.W Mason. The protagonist of this story, Harry Feversham, receives four white feathers as a symbol of his cowardice when he resigns from his job in the armed forces and tries to leave the conflict in Sudan and return home. These feathers are given to the character by some of his peers in the army as well as his fiancé who calls off their engagement.

The premise of the novel revolves around the character of Harry Feversham attempting to earn back the trust and respect of those close to him by returning to fight and kill the enemy. This popular novel therefore entrenched the idea of white feathers being a sign of weakness and lack of courage in the literary realm.

A decade after its publication, an individual called Admiral Charles Penrose Fitzgerald would draw on its imagery in order to launch a campaign aimed at increasing army recruitment, thus leading to the use of the white feather in a public sphere at the outbreak of the First World War.

A military man himself, Fitzgerald was a Vice-Admiral who served in the Royal Navy and was a strong advocate of conscription. He was keen to devise a plan which would bolster the numbers of those enlisting to ensure that all able-bodied men would fulfil their duty to fight.

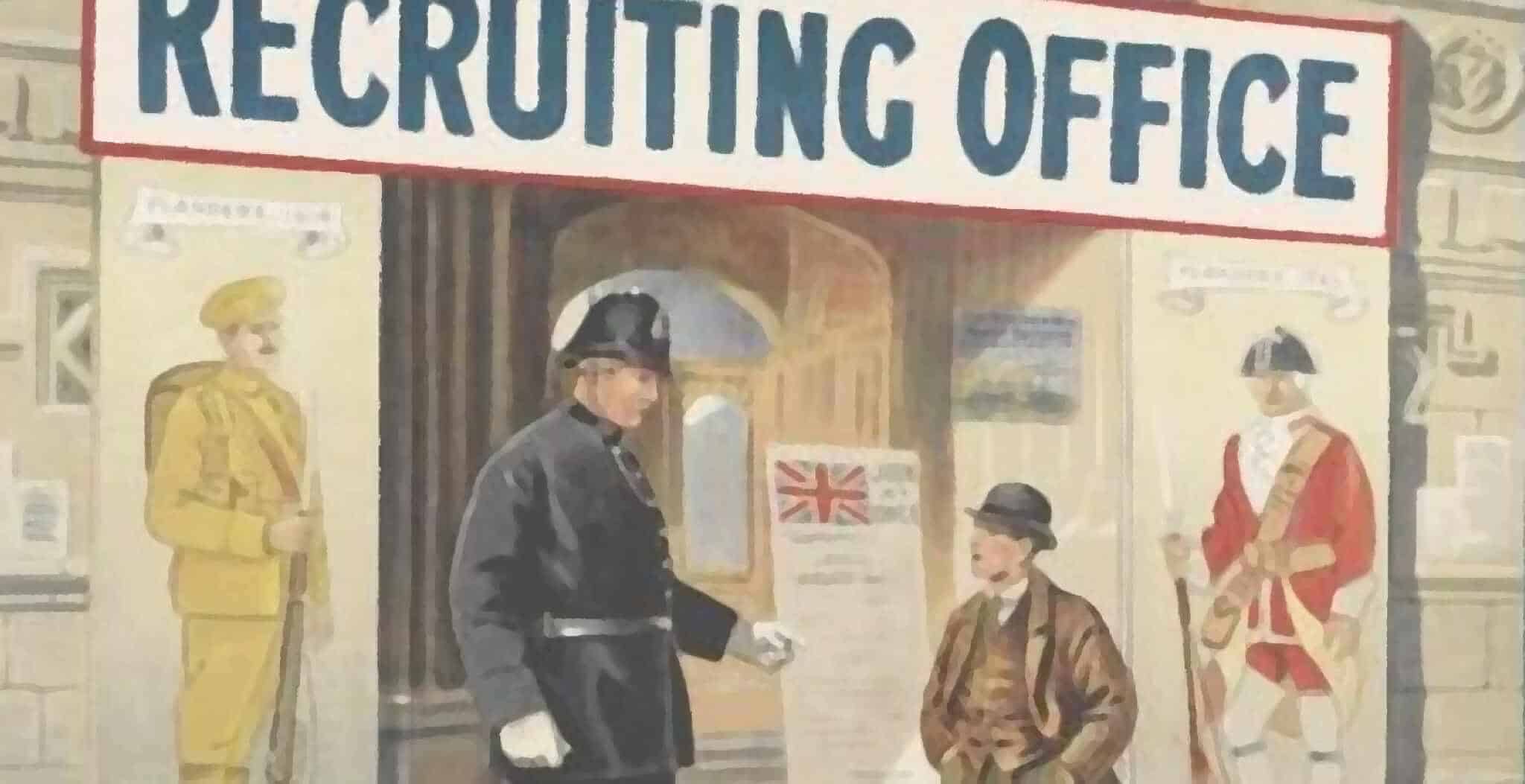

On 30th August 1914, in the city of Folkestone he organised a group of thirty women to hand out white feathers to any men that were not in uniform. Fitzgerald believed that shaming the men into enlisting would be more effective using women and thus the group was founded, becoming known as the White Feather Brigade or the Order of the White Feather.

The movement quickly spread around the country and gained notoriety in the press for their actions. Women in various locations took it upon themselves to hand out white feathers in order to shame those men who were not fulfilling their civic duties and obligations. In response to this, the government was forced to issue badges for those civilian men who were serving in jobs contributing to the war effort, however many men still experienced harassment and coercion.

Prominent lead members of the group included writers Mary Augusta Ward and Emma Orczy, the latter of whom would set up an unofficial organisation called the Women of England’s Active Service League which sought to use women to encourage men to take up active service.

Other significant supporters of the movement included Lord Kitchener who had noted that women could effectively use their female influence in order to ensure that their men upheld their responsibilities.

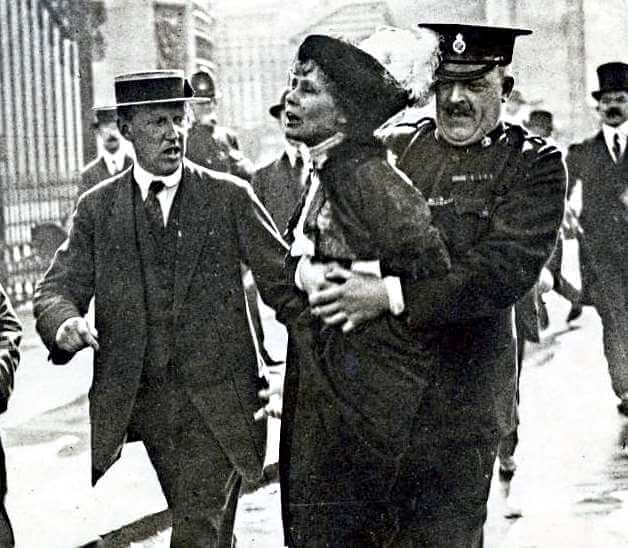

The famous suffragette Emmeline Pankhurst also participated in the movement.

This was an extremely difficult time for men, who were in their thousands risking their lives in one of the most horrendous conflicts the world has ever seen, whilst those at home were bombarded with insults, coercion tactics and tarnished for their lack of courage.

With the White Feather movement gaining greater traction, any young Englishman that the women would deem an eligible proposition for the army would be handed the white feather with the aim of humiliating and defaming the individuals, compelling them to enlist.

In many cases these intimidation tactics worked and led men to enroll in the army and engage in warfare often with disastrous consequences, leading bereaved families to blame the women for the loss of a loved one.

More often than not, many of the women also misjudged their targets, with many men who were on leave from service being handed a white feather. One such anecdote came from a man called Private Ernest Atkins who had returned on leave from the Western Front only to be handed a feather on a tram. Disgusted by this public insult he slapped the woman and said that the boys in Passchendaele would like to see such a feather.

His was a story that was replicated for many serving officers who had to experience such an insult to their service, none more so than Seaman George Samson who received a feather when he was on his way to a reception held in his honour to receive the Victoria Cross as a reward for his bravery at Gallipoli.

In some mortifying cases, they targeted men who had been injured in war, such as army veteran Reuben W. Farrow who was missing his hand after being blown up on the Front. After a woman aggressively asked why he would not do his duty for his country he merely turned around and showed his missing limb causing her to apologise before fleeing from the tram in humiliation.

Other examples included younger men, only sixteen years of age being accosted in the street by groups of women who would yell and scream. James Lovegrove was one such target who after being rejected the first time of applying for being far too small, he simply asked for his measurements to be changed on the form so that he could join.

Whilst the shame for many men was often too much to bear, others, such as the famous Scottish writer Compton Mackenzie who himself had served, simply labelled the group as “idiotic young women”.

Nevertheless, the women involved in the campaign were often fervent in their beliefs and public outcry did very little to dampen their activities.

As the conflict raged on, the government grew more concerned by the group’s activities, especially when so many accusations were levelled at returning soldiers, veterans and those horrifically wounded in war.

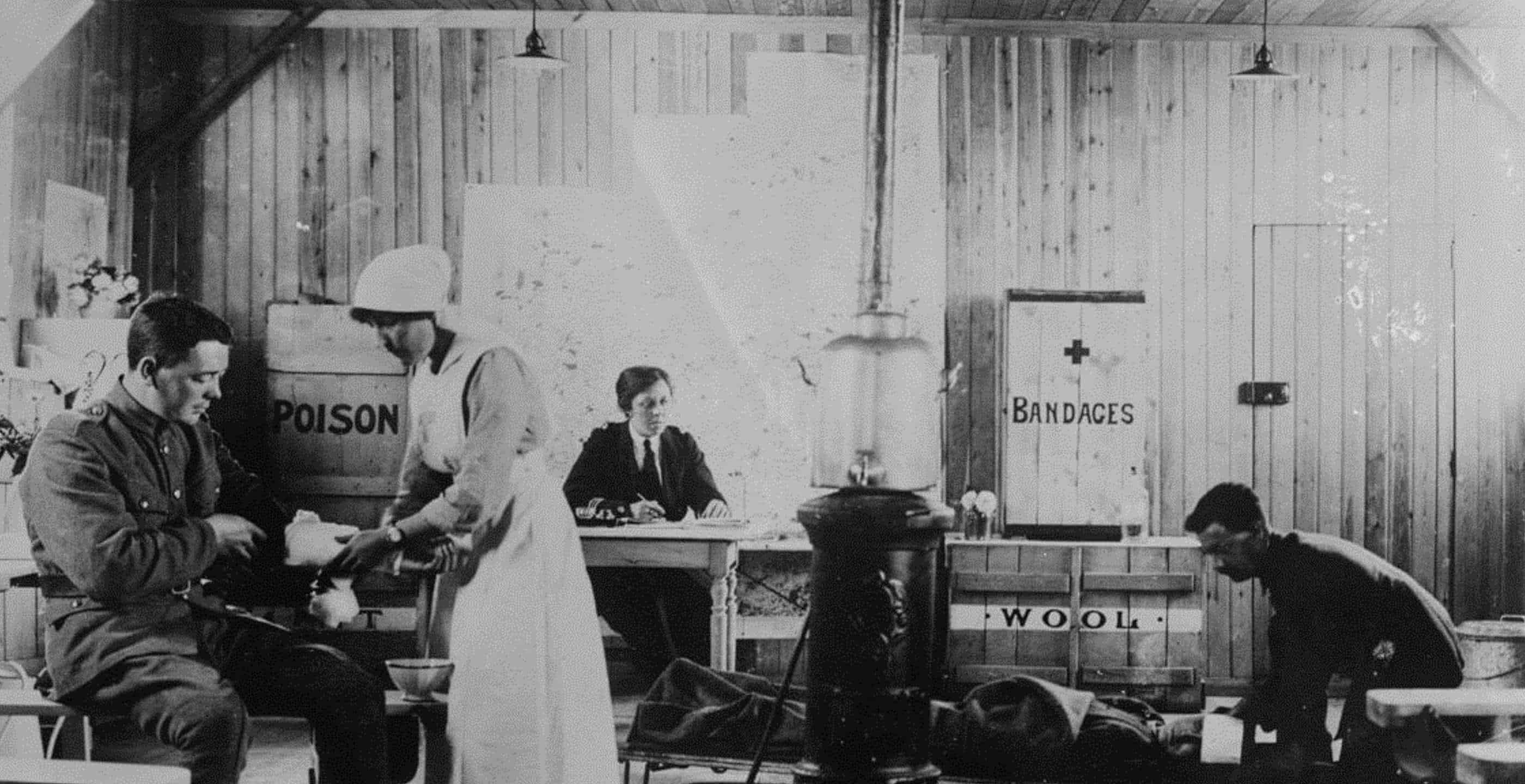

In response to the pressure exerted by the white feather movement, the government had already made the decision to issue badges with “King and Country” written on them. The Home Secretary Reginald McKenna created these badges for employees in industry as well as public servants and other occupations who had been unfairly treated and targeted by the brigade.

Moreover, for the returning veterans who had been discharged, wounded and returned to Britain, the Silver War Badge was given in order for the women not to mistake the returning soldiers who were now plain-clothed citizens. This was introduced in September 1916 as a measure to counteract the growing hostility felt by the military who had often been on the receiving end of the white feather campaign.

Such public displays of shaming had led the white feathers to gain increasing notoriety in the press and public, eventually drawing greater criticism onto themselves.

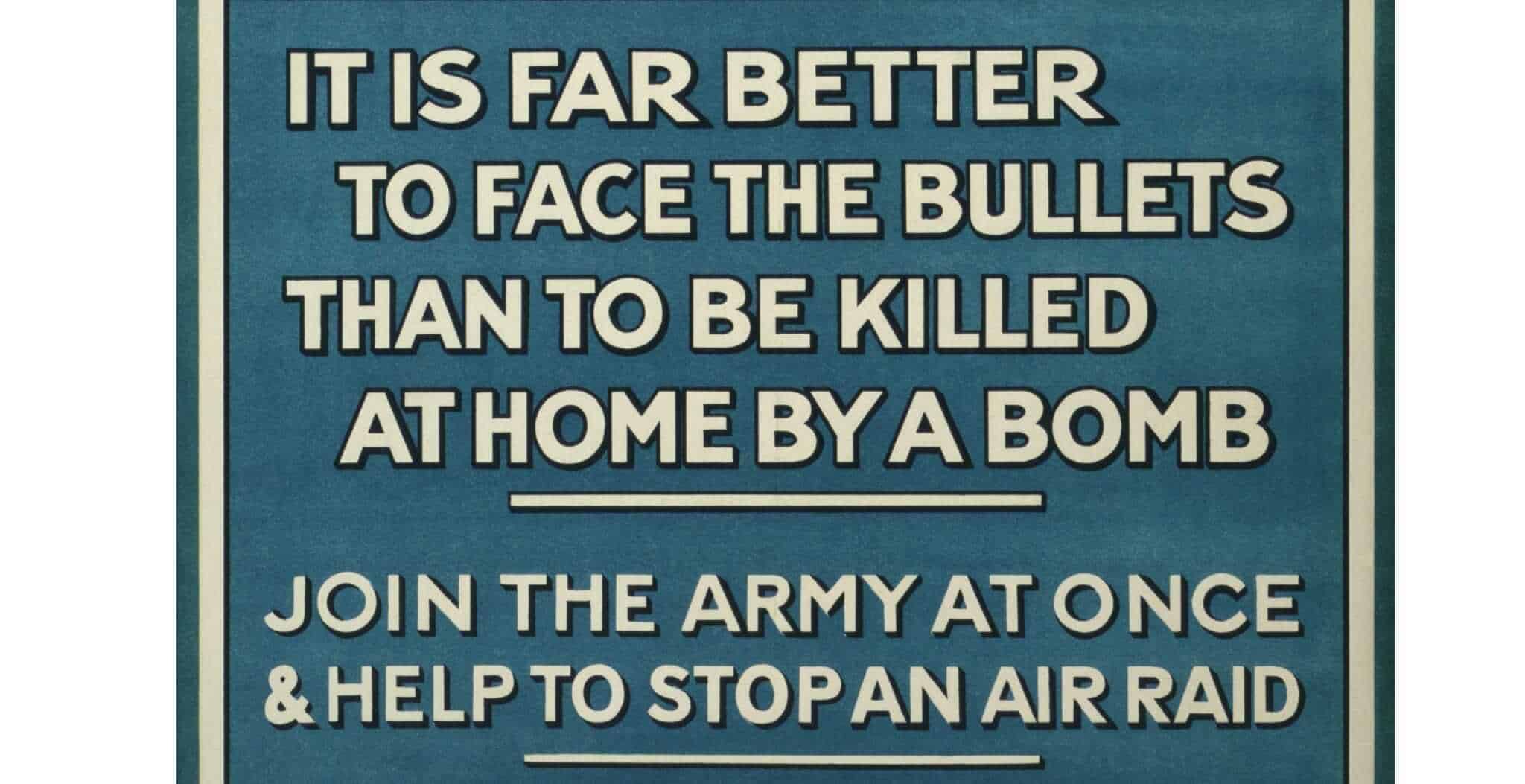

This was a time when gender appeared to be weaponised for the war effort, with masculinity inextricably linked to patriotism and service, whilst femininity was defined by ensuring that their male counterparts fulfilled such obligations. Such propaganda demonstrated this narrative and was commonplace with posters depicting women and children watching departing troops with the caption reading “Women of Britain Say-Go!”

Whilst the female suffrage movement was also in full swing at this time, the white feather movement would lead to harsh public critique of the conduct of those women involved.

Eventually, the movement would face increasing backlash from the public who had enough of the shaming tactics. After the end of the First World War the white feather campaign died a natural death as a propaganda tool and was only briefly reprised in World War Two.

The White Feather movement did prove successful in its aim of encouraging men to sign up and fight. The collateral damage of such a movement was indeed the lives of the men themselves who very often were killed or maimed in one of the bloodiest and ugliest wars Europe has ever witnessed.

Whilst the fighting ended in 1918, the battle over male and female gender roles would continue for much longer, with both sides falling victim to stereotypes and power struggles which raged on in society for years to come.

Jessica Brain is a freelance writer specialising in history. Based in Kent and a lover of all things historical.

Published: 8th January 2022.