The Victorian Workhouse was an institution that was intended to provide work and shelter for poverty stricken people who had no means to support themselves. With the advent of the Poor Law system, Victorian workhouses, designed to deal with the issue of pauperism, in fact became prison systems detaining the most vulnerable in society.

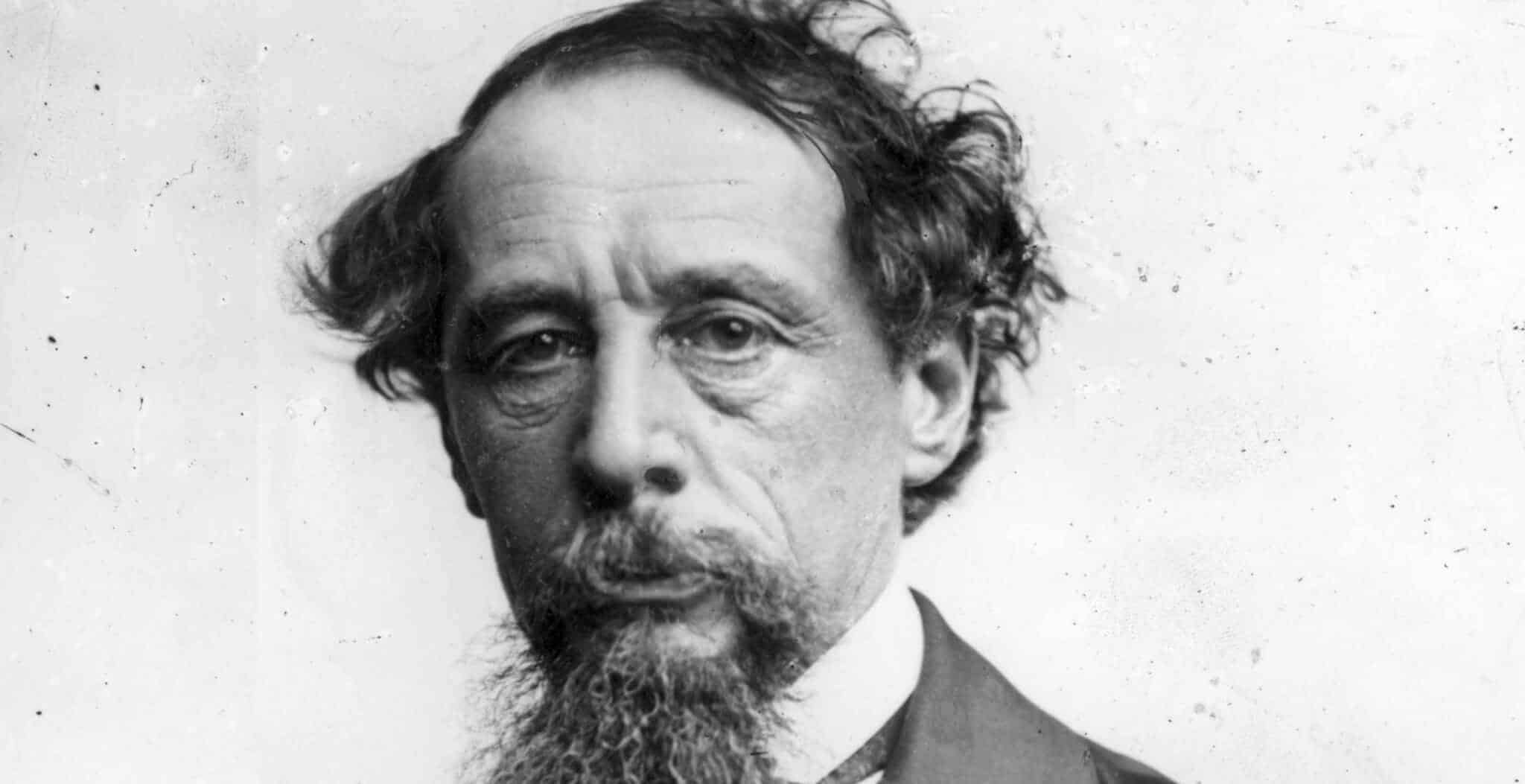

The harsh system of the workhouse became synonymous with the Victorian era, an institution which became known for its terrible conditions, forced child labour, long hours, malnutrition, beatings and neglect. It would become a blight on the social conscience of a generation leading to opposition from the likes of the Charles Dickens.

This famous phrase from Charles Dickens ‘Oliver Twist’ illustrates the very grim realities of a child’s life in the workhouse in this era. Dickens was hoping through his literature to demonstrate the failings of this antiquated system of punishment, forced labour and mistreatment.

The fictional depiction of the character ‘Oliver’ in fact had very real parallels with the official workhouse regulations, with parishes legally forbidding second helpings of food. Dickens thus provided a necessary social commentary in order to shine a light on the unacceptable brutality of the Victorian workhouse.

The exact origins of the workhouse however have a much longer history. They can be traced back to the Poor Law Act of 1388. In the aftermath of the Black Death, labour shortages were a major problem. The movement of workers to other parishes in search of higher paid work was restricted. By enacting laws to deal with vagrancy and prevent social disorder, in reality the laws increased the involvement of the state in its responsibility to the poor.

By the sixteenth century, laws were becoming more distinct and made clear delineations between those who were genuinely unemployed and others who had no intention of working. Furthermore, with King Henry VIII’s Dissolution of the Monasteries in 1536, the attempts at dealing with the poor and vulnerable were made more difficult as the church had been a major source of relief.

By 1576 the law stipulated in the Poor Relief Act that if a person was able and willing, they needed to work in order to receive support. Furthermore in 1601, a further legal framework would make the parish responsible for enacting the poor relief within its geographic boundaries.

This would be the foundation of the principles of the Victorian workhouse, where the state would provide relief and the legal responsibility fell on the parish. The oldest documented example of the workhouse dates back to 1652, although variations of the institution were thought to have predated it.

People who were able to work were thus given the offer of employment in a house of correction, essentially to serve as a punishment for people who were capable of working but were unwilling. This was a system designed to deal with the “persistent idlers”.

With the advent of the 1601 law, other measures included ideas about the construction of homes for the elderly or infirm. The seventeenth century was the era which witnessed an increase in state involvement in pauperism.

In the following years, further acts were brought in which would help to formalise the structure and practice of the workhouse. By 1776, a government survey was conducted on workhouses, finding that in around 1800 institutions, the total capacity numbered around 90,000 places.

Some of the acts included the 1723 Workhouses Test Act which helped to spur the growth of the system. In essence, the act would oblige anyone looking to receive poor relief to enter the workhouse and proceed to work for a set amount of time, regularly, for no pay, in a system called indoor relief.

Furthermore, in 1782 Thomas Gilbert introduced a new act called Relief of the Poor but more commonly known by his name, which was set up to allow parishes to join together to form unions in order to share the costs. These became known as Gilbert Unions and by creating larger groups it was intended to allow for the maintenance of larger workhouses. In practice, very few unions were created and the issue of funding for authorities led to cost cutting solutions.

When enacting the Poor Laws in some cases, some parishes forced horrendous family situations, for example whereby a husband would sell his wife in order to avoid them becoming a burden which would prove costly to the local authorities. The laws brought in throughout the century would only help to entrench the system of the workhouse further into society.

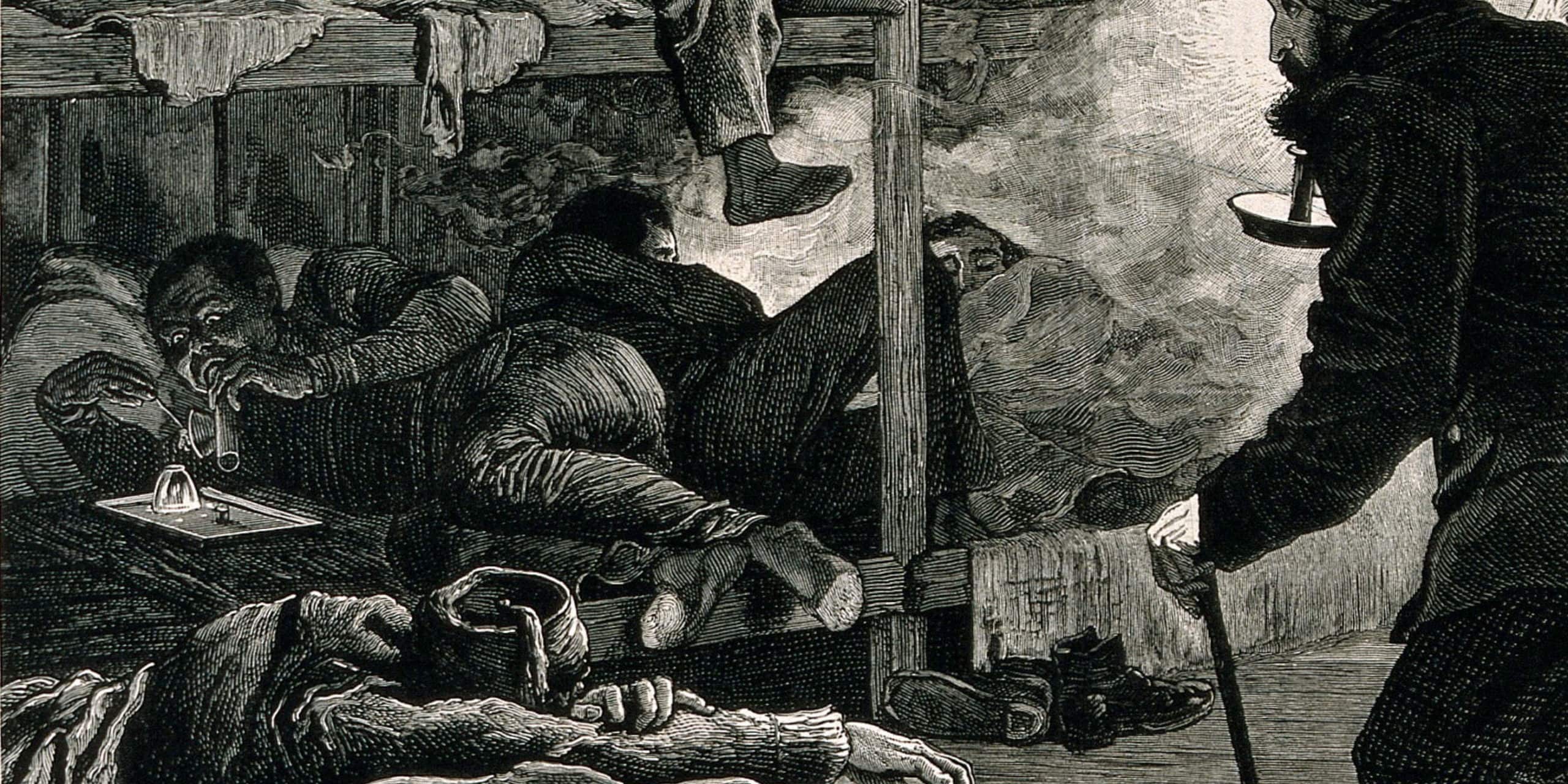

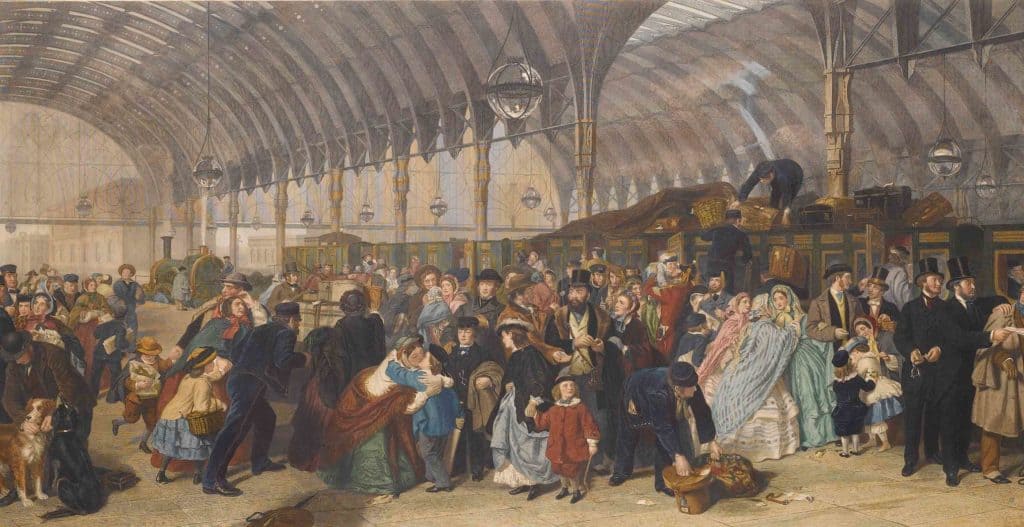

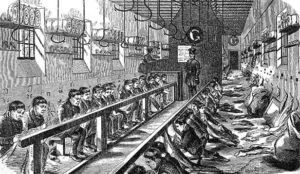

By the 1830’s the majority of parishes had at least one workhouse which would operate with prison-like conditions. Surviving in such places proved perilous, as mortality rates were high especially with diseases such as smallpox and measles spreading like wildfire. Conditions were cramped with beds squashed together, hardly any room to move and with little light. When they were not in their sleeping corners, the inmates were expected to work. A factory-style production line which used children was both unsafe and in the age of industrialisation, focused on profit rather than solving issues of pauperism.

By 1834 the cost of providing poor relief looked set to destroy the system designed to deal with the issue and in response to this, the authorities introduced the Poor Law Amendment Act, more commonly referred to as the New Poor Law. The consensus at the time was that the system of relief was being abused and that a new approach had to be adopted.

The New Poor Law brought about the formation of Poor Law Unions which brought together individual parishes, as well as attempting to discourage the provision of relief for anyone not entering the workhouse. This new system hoped to deal with the financial crisis with some authorities hoping to use the workhouses as profitable endeavours.

Whilst many inmates were unskilled they could be used for hard manual tasks such as crushing bone to make fertiliser as well as picking oakum using a large nail called a spike, a term which would later be used as a colloquial reference to the workhouse.

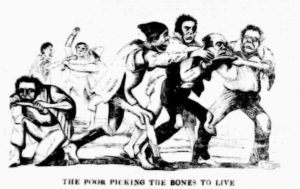

Newspaper illustration from ‘The Penny Satirist’ in 1845, used to illustrate the newspaper’s article about the conditions inside the Andover Union workhouse, where starving inmates ate bones meant for use in fertilizer.

Newspaper illustration from ‘The Penny Satirist’ in 1845, used to illustrate the newspaper’s article about the conditions inside the Andover Union workhouse, where starving inmates ate bones meant for use in fertilizer.

The 1834 Law therefore formally established the Victorian workhouse system which has become so synonymous with the era. This system contributed to the splitting up of families, with people forced to sell what little belongings they had and hoping they could see themselves through this rigorous system.

Now under the new system of Poor Law Unions, the workhouses were run by “Guardians” who were often local businessmen who, as described by Dickens, were merciless administrators who sought profit and delighted in the destitution of others. Whilst of course parishes varied – there were some in the North of England where the “guardians” were said to have adopted a more charitable approach to their guardianship – the inmates of the workhouses across the country would find themselves at the mercy of the characters of their “guardians”.

The conditions were harsh and treatment was cruel with families divided, forcing children to be separated from their parents. Once an individual had entered the workhouse they would be given a uniform to be worn for the entirety of their stay. The inmates were prohibited from talking to one another and were expected to work long hours doing manual labour such as cleaning, cooking and using machinery.

Over time, the workhouse began to evolve once more and instead of the most able-bodied carrying out labour, it became a refuge for the elderly and sick. Moreover, as the nineteenth century drew to a close, people’s attitudes were changing. More and more people were objecting to its cruelty and by 1929 new legislation was introduced which allowed local authorities to take over workhouses as hospitals. The following year, officially workhouses were closed although the volume of people caught up in the system and with no other place to go meant that it would be several years later before the system was totally dismantled.

In 1948 with the introduction of the National Assistance Act the last remnants of the Poor Laws were eradicated and with them, the workhouse institution. Whilst the buildings would be changed, taken over or knocked down, the cultural legacy of the cruel conditions and social savagery would remain an important part of understanding British history.

Jessica Brain is a freelance writer specialising in history. Based in Kent and a lover of all things historical.

Published: 8th August 2019.