In January 1899 Barnum and Bailey’s ‘Greatest Show on Earth’ was a few weeks into its second winter season at London’s Olympia when something extraordinary happened. The performers in the so-called ‘freak show’ rebelled. In possibly the world’s first case of political correctness, they called a meeting to protest at being known as ‘freaks’ and to demand a new name. The move hit the headlines and caused a public sensation. But all was not as it appeared.

In an age uncontrolled by modern advertising regulations, the description of Barnum and Bailey’s Circus as ‘the Greatest Show on Earth’ could well be dismissed as an example of the hype and humbug to be found everywhere at the time. But it was true. The show was unlike anything seen before or since.

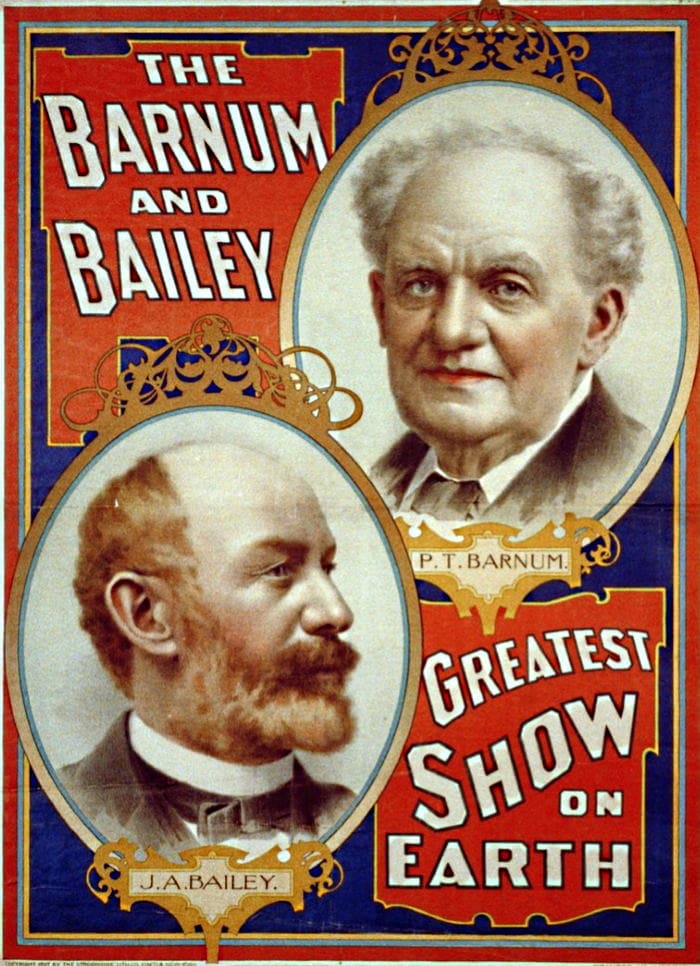

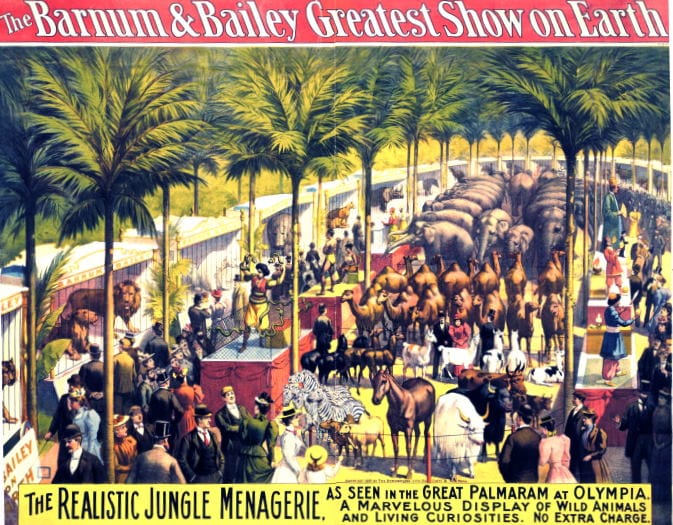

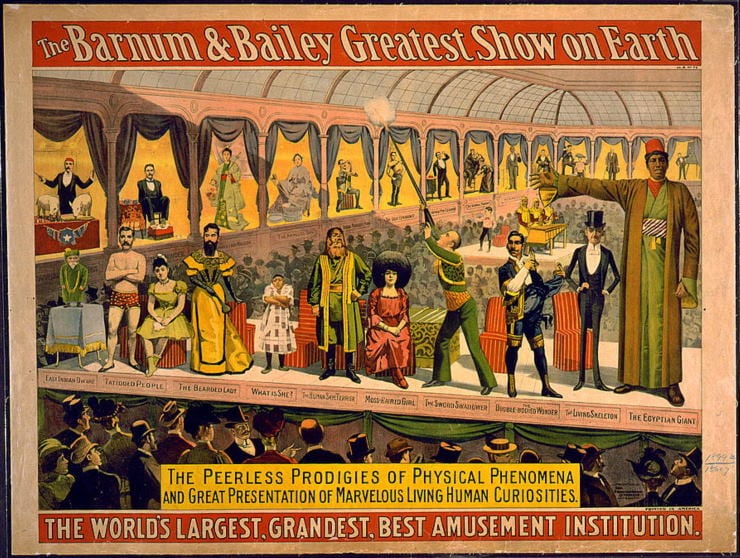

Poster for Barnum and Bailey’s Greatest Show on Earth

It had arrived in Britain in November 1887 for a winter season at Olympia, before setting off on an almost eighty-stop tour of towns and cities across Britain. Its scale was epic, requiring four trains each made up of specially modified railway wagons to transport it from showground to showground. The workforce was 860 strong, including 250 performers. There were 460 horses and 660 other animals.

The circus itself comprised three rings, all in use at the same time, as well as two platforms and a track around the outside used for horse, pony and chariot racing. The entertainment in the rings and on the platforms was continuous, with breaks only long enough for one set of performers to replace another. Even the breaks were covered by the appearance of clowns. All in all there were nearly 50 acts – a newspaper advertisement described some of them: ‘Trained animals, aerial displays, weird magic illusions, mid-air wonders, ground and lofty tumbling, aquatic feats, sub aqueous diversions, high class equestrianism, 3 herds of elephants, 2 droves of camels, jumping horses and ponies and races of all kind.’

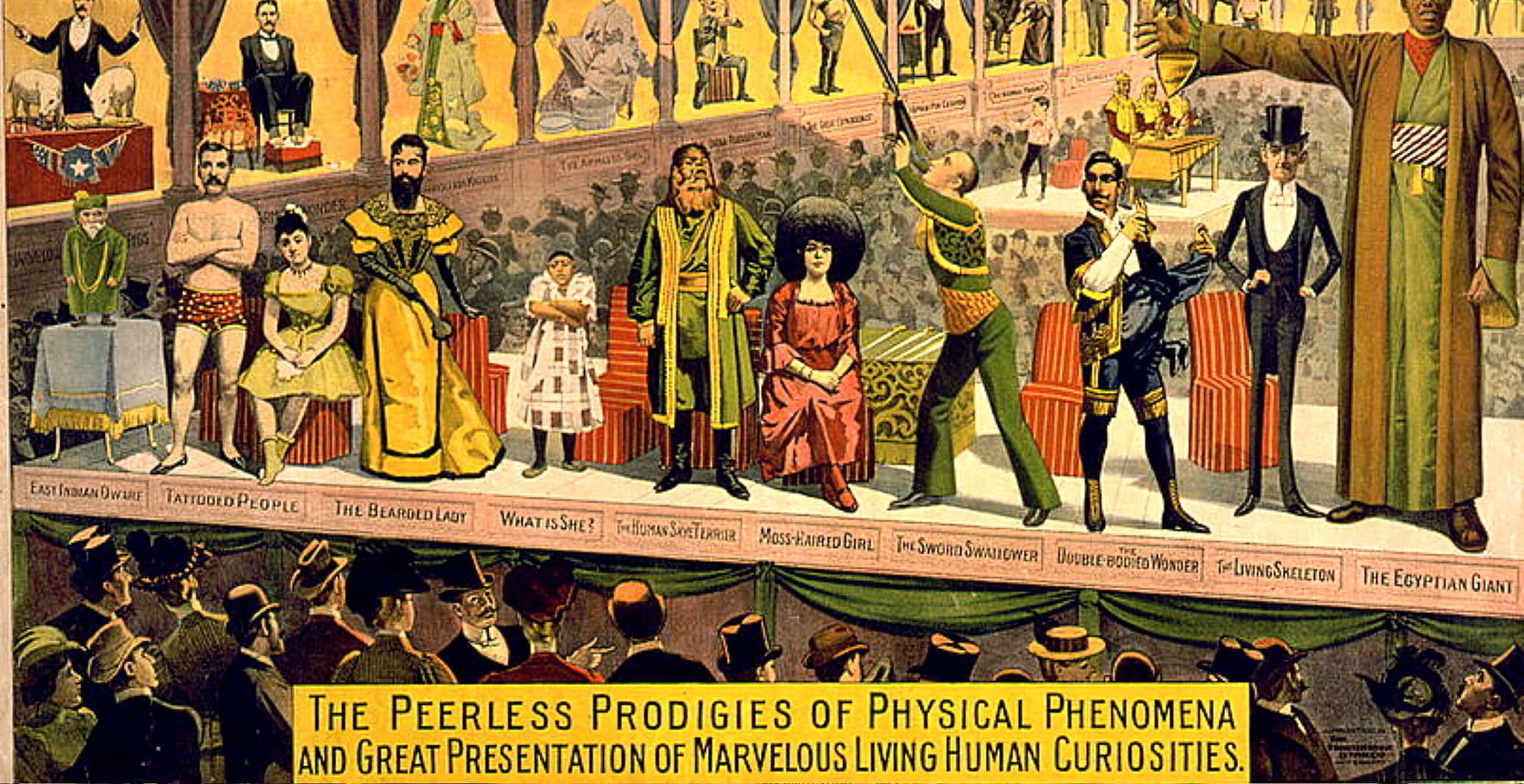

In addition to the circus, there was a huge menagerie and more than 40 performers in the ‘freak show’. So important were these additional attractions that a separate illustrated booklet ‘The Wonder Book of Freaks and Animals‘ could be bought by visitors. This gave details of the people and animals on display.

Freak shows were extremely popular during the Victorian period. It was P.T. Barnum himself who was largely instrumental in introducing them into popular culture. In his first foray into show business in 1835, he bought an elderly, frail and blind slave named Joice Heth who he claimed was 161 years old and had been George Washington’s nurse when he was a child. He took her on tour and charged a few cents for people to meet her. An autopsy when she died a year later revealed that far from being over 160 she was probably no more than 80. In 1844 Barnum caused a sensation when he took the dwarf Tom Thumb to Buckingham Palace to be presented to Queen Victoria. When Barnum went into business with James Bailey in 1881, the Greatest Show on Earth was born and the freak show became an important element.

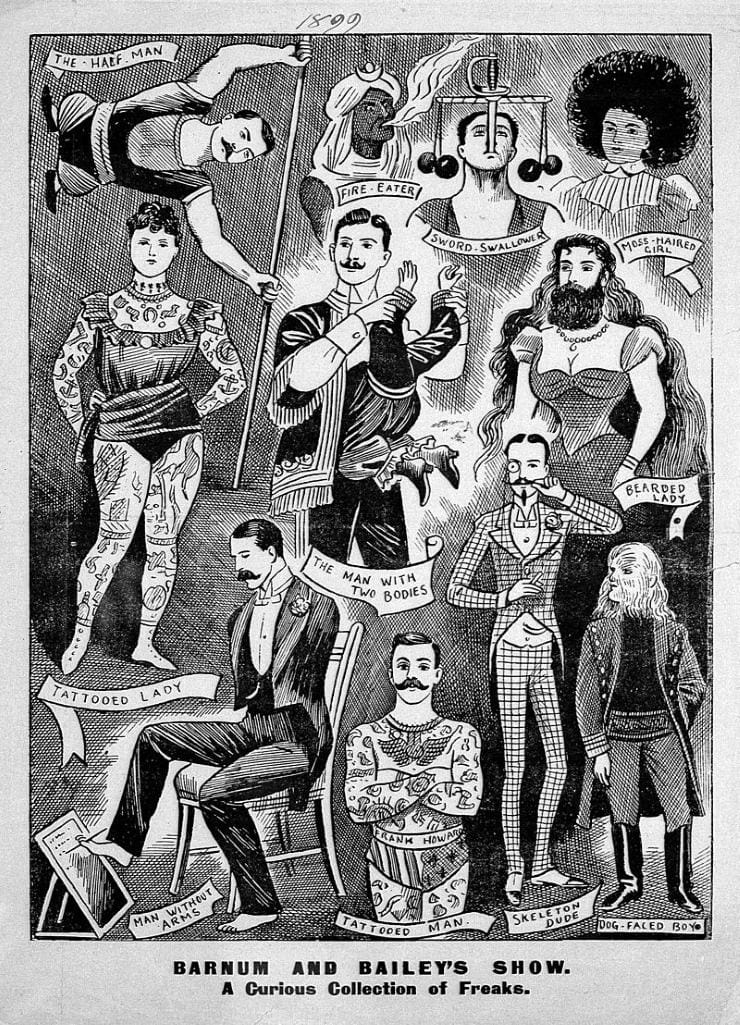

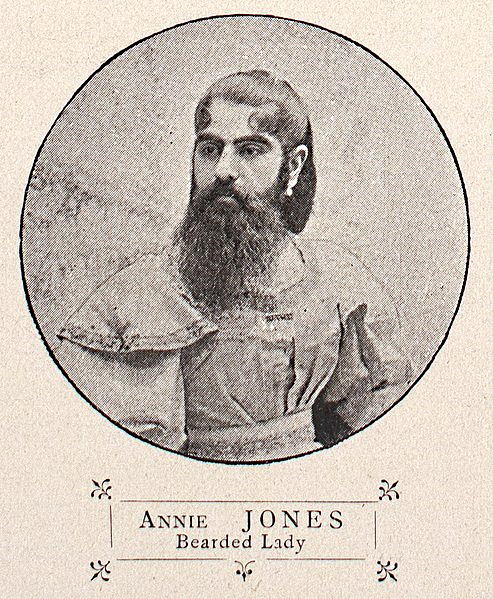

The Barnum and Bailey freaks appeared on a long dais in the centre of a marquee around which walked a ‘lecturer’ who described the characteristics of each individual. They included Jo-Jo the Human Sky Terrier, whose face was covered with a thick growth of long silky hair ‘giving him the appearance of a dog’; Young Herman the Great Expansionist said to be able to expand his chest by more than 16 inches and break chains with its force; Annie Jones, the Bearded Lady; Charles Tripp the Armless Wonder; James Morris the Man with Elastic Skin; Hassan Ali, The Egyptian Giant, who stood 7 feet 11inches; Khusania, the Hindu Dwarf, standing just 22 inches; James Coffey the Skelton Dude said to weigh just two stone nine pounds; Billy Wells the Iron Skull Man who broke rocks on his head and Sol Stone, known as the Lightning Calculator because of the speed with which he could solve mathematical problems.

These were among those who joined the revolt in 1899. On the morning of Friday January 6th Annie Jones, the Bearded Lady, called a meeting to protest at the use of the word ‘freak’. Billy Wells, the Iron Skull Man, nominated the department’s manager Lew Graham as chairman. Annie Jones then outlined her objections to the word ‘freak’. To her it meant something like ‘fright’ and if a beard made a lady a fright then it must also apply to a man. No man possessing as fine a beard as hers would call himself a fright, she added.

The meeting went on to approve a strongly worded resolution: “That we, a majority of the living human curiosities at the Barnum and Bailey Show, emphatically protest against the application of the word ‘freak’ to us, and severely condemn its general assignment to those who, for their benefit or otherwise, were created differently from the human family as the latter exist today, and that, in the opinion of many, some of us are really the development of a higher type and are superior persons, inasmuch some of us are gifted with extraordinary attributes not apparent in ordinary beings.”

Annie Jones, the Bearded Lady

The meeting was unanimous that another name should be adopted to replace the offending word. But with no suggestions forthcoming, it was adjourned to allow for discussion.

The news of the revolt and suggestions that the freaks might even go on strike provoked a media frenzy across Britain. Articles were written on the ‘final awakening of personal pride in abnormal species of the human race’. An avalanche of suggestions for a new name descended on Olympia.

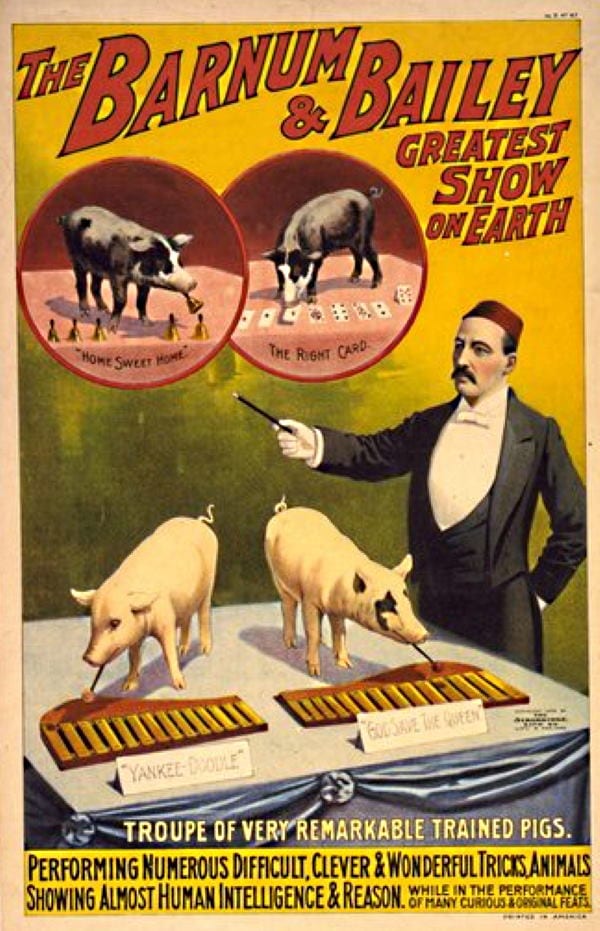

On the afternoon of Sunday January 15th the freaks met again. Sol Stone, the Lightning Calculator was in the chair and Charles Tripp took notes holding a pen between his toes. Mr Stone demanded to know why the rest of the entertainers in the show were called artists while they were dubbed freaks. He insisted that the development of any one particular side of a person’s character did not make them a freak. He, for instance, was an exceptional mathematician but he was not any more of a freak than Sir Henry Irving because he was a great actor. Billy Wells, the Iron Skull man said that far from describing their peculiarities as ‘freakish’ the public admired and envied them. On a lighter note Mr Baker, the owner of a troupe of musical pigs, said he didn’t might being called a freak but he couldn’t bear to hear his pets so described.

The meeting heard a litany of suggestions for new names sent in from around the country. These included Ambiguities, Anomalies, Curios, Deviations, Inexplicables, Peculiar People, Uniques, Unusuals, Vagaries and even Whim-wams.

After lengthy discussion the word ‘ Prodigies’, which had been suggested by Canon Albert Wilberforce of Westminster Abbey, was deemed most acceptable. Put to the vote the suggestion attracted 21 supporters, 11 voted for Human Marvels and there was one vote each for 10 other names.

After the meeting a delegation was dispatched to see James Bailey, who was now in sole charge following Barnum’s death nine years earlier. It was apparently well received and Bailey immediately ordered that all signs and publicity material should now refer to Prodigies rather than Freaks.

The press department, always on the look-out for a good story, immediately swung into action and news of the ‘Revolt of the Freaks’ was published around the world.

The Prodigies were satisfied and life returned to normal. The Greatest Show on Earth finished its winter season at Olympia before touring Britain through the summer. The following year it moved to Europe.

And that might have been the end of the matter. But four years later the word ‘freaks’ had returned and a similar protest meeting was called in New York while the show was playing a season at Madison Square Garden. The arguments put forward were strangely similar to those aired in London. Many journalists were suspicious but they put their doubts to one side and the story of the second ’freaks’ revolt’ hit the headlines.

Eventually the truth emerged. The Washington Herald revealed the whole thing had been a massive publicity stunt. The man credited with dreaming it up was none other than Sol Stone the Lightning Calculator. But the mastermind behind the whole thing was Richard F.’Tody’ Hamilton, the long serving and legendary press agent for Barnum and Bailey. Because of his flair for language, his use of adjectives, hyperbole and alliteration, he became one of the most well-known men of his age.

He was said to produce two-million words of promotional copy a year and memorised more adjectives than any man alive. Along with men like John M. Burke of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show, he was part of the first generation of press agents – the founding fathers of the modern industry.

P.T. Barnum himself said he owed more of his success to Hamilton than any other man. He’d joined the Greatest Show on Earth when it began in 1881 and remained for more than a quarter of century. In 1899, nearly a decade after Barnum’s death, he was still doing his brilliant best to keep the show firmly in the headlines, never more so than in the extraordinary story of the ‘Freaks’ Revolt’. In a candid moment Hamilton said it had been so successful he was almost ashamed of himself.

David Dunford attended the University of Essex, graduating with a degree in Government. He joined Essex County Newspapers in Colchester as a reporter and later became an assistant editor. He later moved to the BBC in London where he wrote and edited news bulletins for all BBC Radio outlets. He later became Editor of the BBC General News Service, responsible for providing news and current affairs for stations around the country. In 2003 he was Editor of all BBC local radio and regional television coverage of the second Gulf War.

After taking early retirement he became a visiting lecturer in radio journalism at the University of the Arts in London.

In 2014 he returned to Essex University to study for an MA in History which he was awarded with distinction. He has written books on the history of horse racing in Chelmsford and on the visits of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show to Essex in the early 1900s as well as numerous newspaper and magazine articles.

Published 8th March 2023