The neat stack of old letters held together by a faded blue ribbon lay untouched for years in a box in the attic. I knew they were letters which my father wrote to my mother when he was stationed in Britain during the early years of World War II. Perhaps a respect for their privacy held me back from reading them or just my own busy life didn’t give me time.

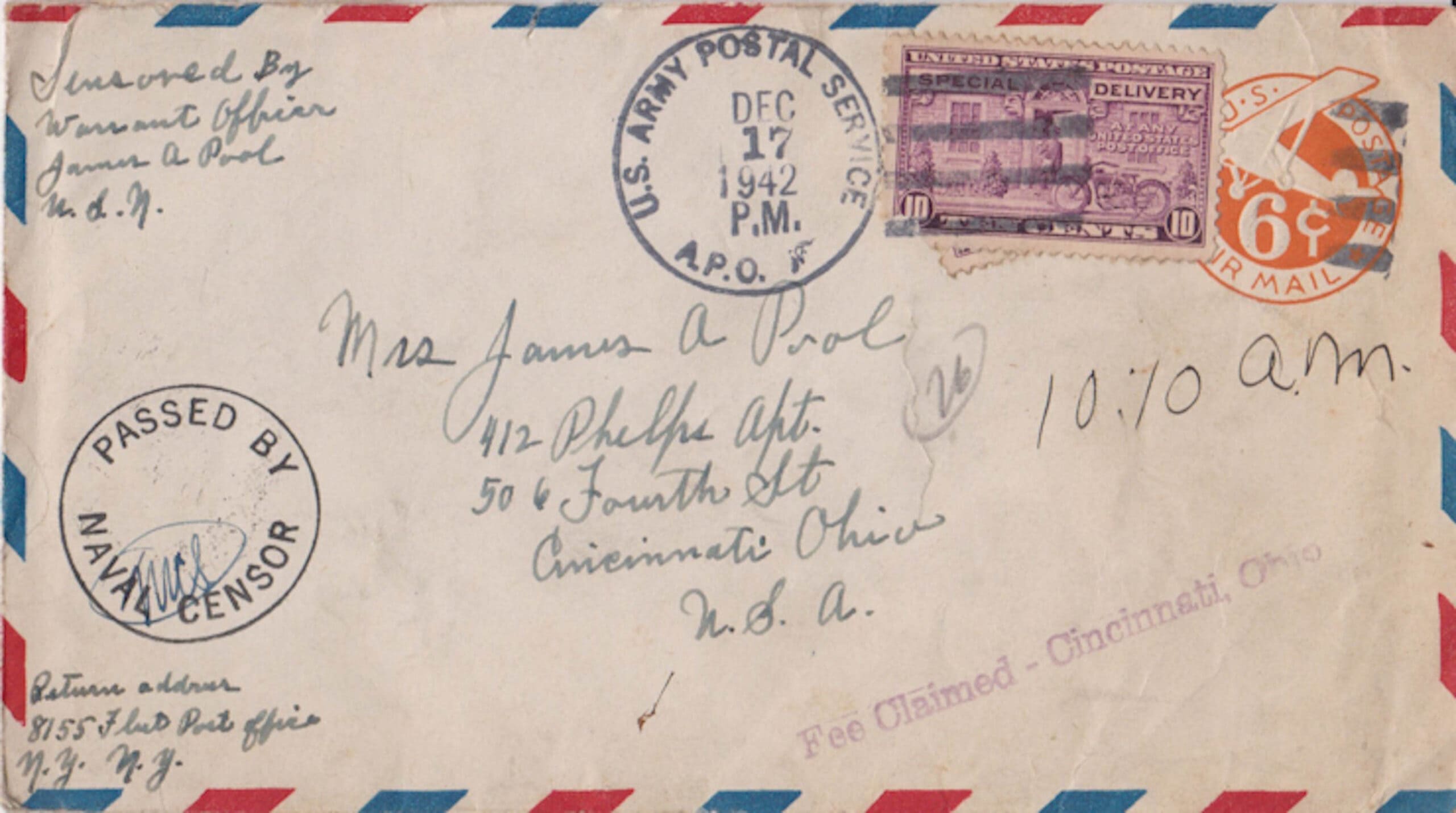

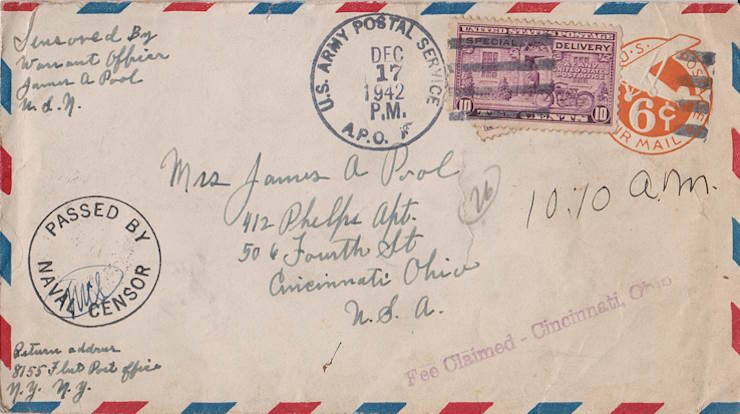

About a year ago, I untied that faded ribbon and began to read these letters written by my father — Chief Warrant Officer James A. Pool, US Navy, to my mother, Geneva, and have been richly rewarded with a wonderful love story during a time of war. Because my mother told him not to write anything private in his letters, and because military censorship prevented him from revealing details about his work, he would often write about shopping and about the British way of life.

After a rough trans-Atlantic voyage on the RMS Queen Mary from New York Harbor, James and his comrades from the 29th Naval Construction Battalion (known as CBs or “Seabees”) were first stationed in Rosneath, Scotland, one of the main bases established to serve the massive US naval forces coming to join the Allied forces in their attack on the German fortified coast of Normandy. The mission of these Seabees was not only to prepare the bases for housing and fueling stations but also to give logistical support to amphibious forces.

In one of his early letters from Scotland, James commented that some people in the small villages told him that he was the first American they had ever seen– and likewise he had never seen Scottish highlanders wearing kilts before. When he would get leave ashore, he and a friend would drive their jeep to Edinburgh where they would go shopping and then visit the British officer’s club.

Due to food shortages and rationing, they would be lucky to get a decent meal. At the bar they would see military men wearing their national uniforms–Polish, Free French, Canadians, British and Americans all drinking together.

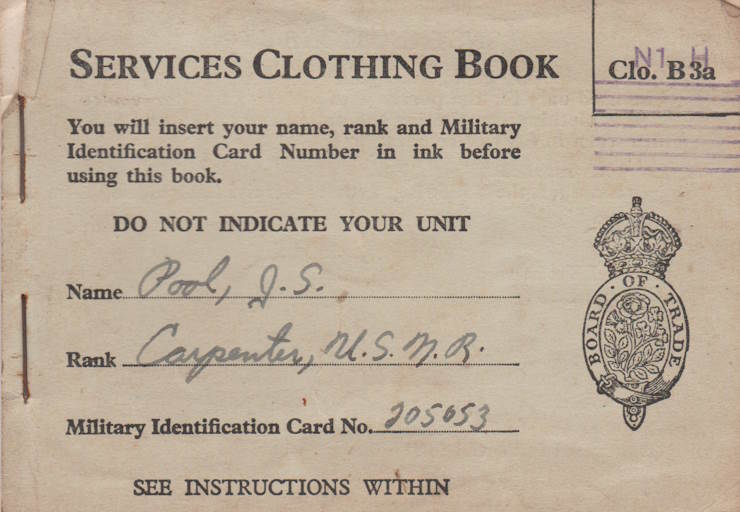

Because of the increased demand for military clothing and fabrics, the British government had started rationing civilian clothing in 1941. Civilians were permitted to purchase what they wanted but limited to the amount equal to 66 coupons. Even US troops were given coupon books so they could buy clothing items. James had his name, rank and military ID number on his “Services Clothing Book,” which had instructions on the articles of clothing that could be purchased by the coupons marked “Special.”

Ordinarily when off-duty, James would wear the traditional Service Dress Blues — a dark navy wool jacket, with double breasted gold buttons. Under this was a white shirt with a black neck tie. Depending on the season, the officer wore a either a white or navy colored cap with visor centered with a naval anchor insignia. On one of his trips into London for business at the Embassy, James complained that naval regulations required him to wear his dress uniform and even carry his gloves in public, despite the summer heat— “it was hotter than the devil.”

On his first trip to London, he was impressed with how they cleaned up from the enemy aerial bombing and “business goes on as if nothing happened.” When he went to Burberry’s store near Piccadilly, he asked them to suggest a bootmaker in the area. One well-known department store he visited was Selfridge’s, created by an American businessman. James was astounded at its size and its “different way of selling”.

Unbeknownst to James at that time, there was a secret communications system in the basement of Selfridge’s called Sigsaly, which protected trans-Atlantic messages between President Roosevelt and Prime Minister Churchill. The basement of another department store — Fortnum & Mason’s also in the Piccadilly area — was used as a bomb shelter when necessary. Although the intense bombing of London during the “Blitz” from September 1940 to May 1941 had ended, the Germans still would periodically bomb London, including when James was there in July of 1943: “There was a bomb raid on the first night, about 1:30 am and another two nights later,” he recalled. Fortunately, it wasn’t near the Officer’s Red Cross Club where he was staying.

The next month James took 50 enlisted men to Falmouth for amphibious exercises to prepare for D-Day. He wrote to his wife about returning to shore on a landing barge: “The seas were so rough they broke over the top of the boat and hit you in the face.” There was loss of many lives during these dangerous sea exercises, especially resulting from surprise attacks by German submarines. When a sailor in his battalion was killed, James had to pack the belongings and uniform of the deceased to send back to his family.

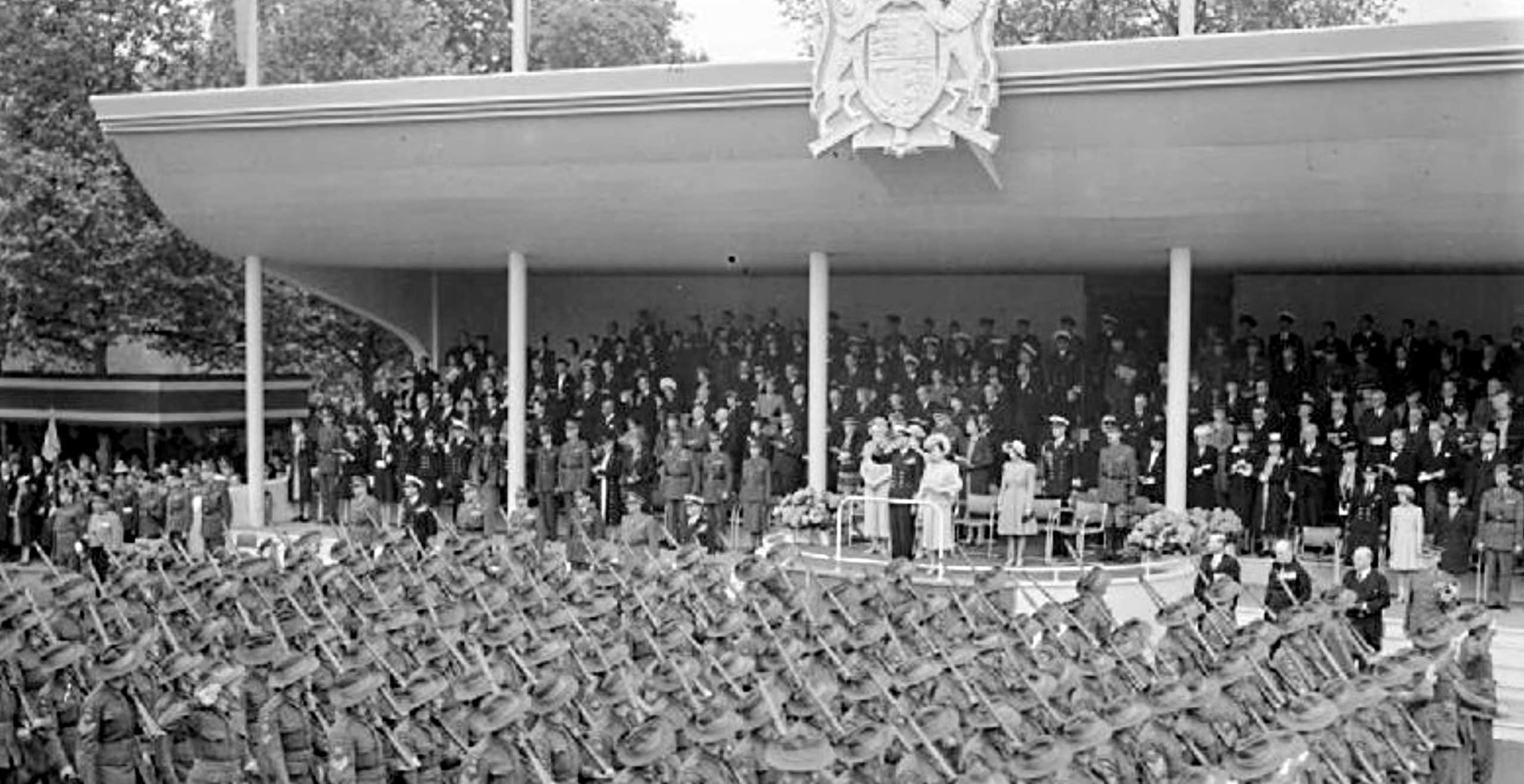

For most of the 21 months that the 29th NCB served in Britain, the Seabees wore coveralls or wool trousers and rubber boots, because the heavy rains had them up to their ankles in mud. When they were at sea, they were wearing oil skin coats and fur-lined boots to protect themselves from the icy salt water. By March 1944 millions of American troops had arrived in Britain and were filling the roads and fields of southern England. James said it sure had changed since he had been there a year ago. “Now you see Americans all over and the bays are full of American ships.” This meant he couldn’t buy any good gifts for Ginny, because “they are all bought out.”

As time grew closer to the invasion date, any information about troop movements was top secret. When James served as the censor for his company, he had to read all the letters his men wrote. He wrote to Ginny, “I wish I could tell you more, but I’d never hear the end of it if I did.” He often told her how much he missed her and knew from the letters he censored that most of the men were homesick for their loved ones too. James replied to one of her letters: “Sure was glad to hear that you still have the black velvet suit and that it came back in style. I’d give anything in the world to see you in it.” He always signed off his letters: “With oceans of love and tons of kisses.”

Although General Eisenhower had to postpone D-Day by one day because of bad weather, all the troops anticipated the coming “big show”. On June 2, 1944, James wrote: “This might be the last news for a while—guess you know why.”

The Seabees played a critical role in almost every aspect of the Normandy invasion — from the underwater demolition teams, to operating hundreds of landing crafts and Rhino barges to bringing thousands of Allied troops and tons of vehicles and equipment to the beaches. James was one of the lucky ones to survive and return home in 1945. After all these years, my father’s naval jacket and cap have an honored place in my closet.

Suzanne Pool-Camp is the daughter of James A. Pool, and wife of Col. Richard Camp (USMC, Retired). They live in Fredericksburg, VA and are both writers and military historians.

Published: 27th June 2024