June 1940, the darkest days of the Second World War; France has fallen, bringing 30,000 Polish military personnel across the Channel, including about 8,500 pilots. Having fought the German juggernaut unsuccessfully in Poland and France, these desperate exiles christen Britain ‘Last Hope Island’. Churchill declares to the Polish Prime Minister in Exile “We shall conquer together or we shall die together” and the two agree to establish two Polish fighter wings; No. 302 ‘Poznan’ Squadron and No. 303 ‘Kosciuszko’ Squadron.

Yet despite the Polish pilots’ extensive combat experience, the British – like the French before them – tended to credit German propaganda which boasted that the Polish Air Force had been destroyed so quickly due to the ineptitude of its pilots. Flight Lieutenant John Kent who was posted to 303 Squadron summed up the feeling in his memoirs, ‘All I knew about the Polish Air Force was that it had only lasted about three days against the Luftwaffe, and I had no reason to suppose that they would shine any more brightly operating from England’. The language gap made the RAF even more sceptical about the ‘newcomers’ combat potential and teaching them ‘British tactics’ became a top priority. Consequently Nos. 302 and 303 Squadrons were ordered to ride tricycles – equipped with radios, speedometers and compasses – around airfields in practice formations. The battle-hardened Poles did not take kindly to such treatment but they did not have to wait long to prove their mettle.

On August 13 Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring declared the arrival of ‘Adler Tag’ (Eagle Day), signalling the commencement of the Luftwaffe operation to destroy the RAF. By August 19th British losses were so significant that the Air Ministry cut the training time for recruits to two weeks (compared to six months before the war). On August 30, 303 Squadron were carrying out training manoeuvres over Hertfordshire when Flying Officer Ludwik Paszkiewicz spotted a large formation of German bombers and fighters. Paszkiewicz radioed his Squadron Leader Ronald Kellet with the words “Hullo, Apany Leader, bandits at 10 o’clock.” When Kellet did not deign to respond, Paszkiewicz broke formation and charged a Messerschmitt Me-110 and in the ensuing dogfight he and another Hurricane pilot shot the German plane down in flames.

This episode was later immortalised in the ‘Repeat Please’ scene from the Battle of Britain (1969). On his return to base Paszkiewicz was severely reprimanded for ill-discipline and then congratulated for making the squadron’s first kill. Later that evening Kellet put a call through to Fighter Command, declaring ‘Under the circumstances, sir, I do think we might call them operational’. Considering the RAF had lost nearly 100 pilots during the previous week alone, Fighter Command was in no mood to argue.

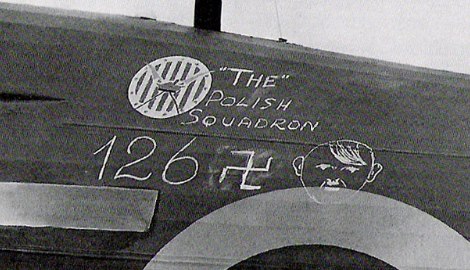

The next day, August 31st, 303 Squadron went into action and during just 15 minutes of combat managed to down 6 Messerschmitts without any losses. In a peculiar twist of fate, 303 Squadron’s first day in combat came exactly one year after the Nazi invasion of Poland. In the following weeks the Squadron notched up dozens of downed enemy aircraft and hundreds of sorties. In just 42 days 303 Squadron shot down 126 German planes, becoming the most successful Fighter Command unit in the Battle of Britain. Nine of the Squadron’s pilots qualified as ‘aces’ for shooting down 5 or more enemy planes, including Sergeant Josef Frantisek, a Czech flying with the Poles who scored 17 downed planes. Overall the Squadron scored nearly three times the number of kills of the average British fighter squadron with one third the casualty rate. In fact, the Polish record was so impressive that Stanley Vincent, the RAF commander of the base at Northolt, took it upon himself to verify their claims.

Following the squadron into combat Vincent witnessed how the Poles dived at the German bombers in their Hurricanes ‘with near suicidal impetus’. On landing back at base Vincent exclaimed ‘My God, they are doing it’. Indeed, the success of the Poles was partly due to their preference for charging enemy formations and only opening fire at close quarters – a far cry from the RAF’s squadron manoeuvre tactics but highly effective nonetheless. One RAF pilot noted with admiration ‘When they go tearing into the enemy bombers and fighters they go so close you would think they were going to collide’.

The Polish pilots’ exploits and derring-do won them affection and admiration throughout England. Richard Cobb relates how one Polish pilot who had been shot down over the South of England was invited to join a longstanding Sunday afternoon doubles tennis match when the fourth partner failed to materialize. Another pilot came down in a south London back garden and fell at the feet of a girl, whom he married two months later. A third Pole, Czestaw Tarkowski, was spared a lynching by telling the aggressive locals to ‘F… off’, to which they responded, ‘He’s one of ours!’

In total 31 out of the 145 Polish pilots who took part in the Battle of Britain died in action, while the Polish War Memorial at RAF Northolt commemorates 1903 personnel killed. The Commander-in-Chief of Fighter Command, Air Chief Marshal Sir Hugh Dowding, was blunter in his assessment, ‘Had it not been for the magnificent work of the Polish squadrons and their unsurpassed gallantry, I hesitate to say that the outcome of battle would have been the same’. This assessment was echoed by the Secretary of State for the Air Force and indeed, during some of the most desperate points of the battle, the RAF had ‘only 350 pilots to scramble, of which nearly 100 were Poles’.

Yet at the end of the war Polish troops were not allowed to participate in the Allied Victory Parade so as not to aggravate Joseph Stalin. Brexiteers or not, we should all be grateful for the sacrifice made by so few for so many. Without the two squadrons of ‘plucky Poles’, it is eminently possible that there would neither be a Britain, nor an EU to vote out of.

Joss Meakins is a graduate student at Columbia University New York, studying Russian and International Politics. Prior to Columbia he graduated from Cambridge with a B.A in French and Russian. His primary research interests include Russia and the former Soviet Union, reforms in Ukraine and Russia’s relationship with NATO.

Published: 13th January 2015.

Footnote added: 23rd April 2024. Re Polish pilots in WW11. I was on National Service in 1950. One weekend we were on exercise in a spider accommodation near Dagenham, Essex. There were many notices around the walls in two languages English and Polish. The English said: “Fighting with broken glass is prohibited”