Cardiff made my father.

Thomas Gareth Thomas was born in the city on 13 July 1936 at 154 Inverness Place, Roath. Gareth Thomas is, of course, a remarkably common name in Wales. Over the years, his namesakes included a well-known 1970s actor, several politicians and academics and more than one Wales international rugby player, to mention only a few. It was a source of amusement all his life.

Of Cardiganshire origins, from the farmlands around Cilgerran, Newquay and Aberaeron, Gareth’s family had two main branches: Thomas and Jones. As with so many Welsh families, the irresistible lure of industrial jobs in the 19th century had drawn them like a magnet to South Wales, to the coalfields, iron and steel works of Merthyr and Dowlais. By the 1870s, both families were Dowlais fixtures, staunch Congregationalists of the local Bethania Chapel, tempered by choral, friendly society and Eisteddfod enthusiasms.

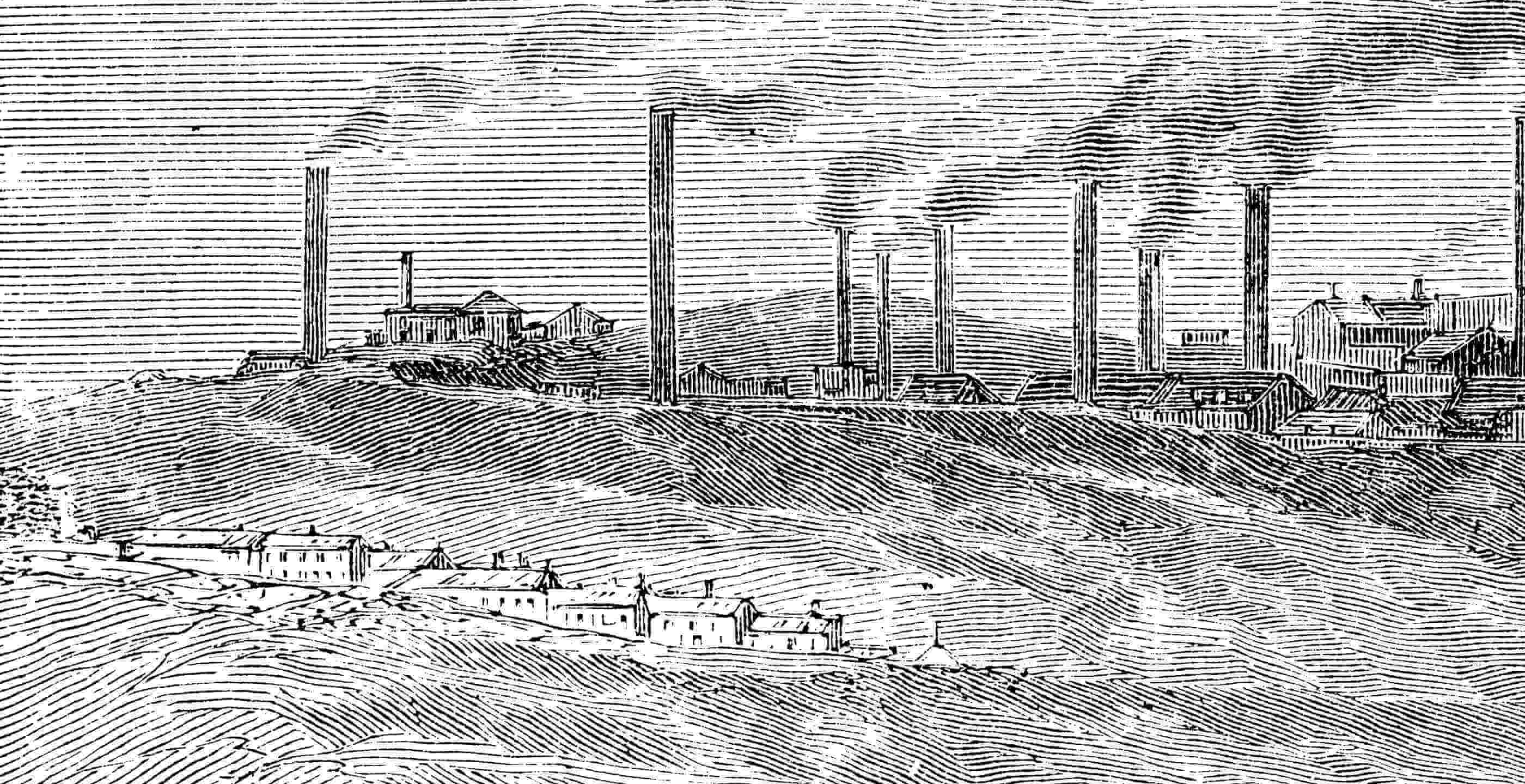

Gareth’s father, Samuel (‘Tom’) Thomas was employed by the Guest, Keen and Nettlefolds (GKN) steelworks in Dowlais, as a stationary engine driver, having entered as an apprentice in 1907. Formerly the Dowlais Iron Works, the plant had supplied cannonballs to the British Army during the Napoleonic Wars and produced steel for munitions around the clock during the First World War (1914-1918). In 1919, Samuel married Catherine Jones at the Register Office, Merthyr. They produced four children: Jane, Gwen, Enid and my father, Gareth. Theirs was a community of many apparent certainties, within a flourishing coal and steel industry, supplying the hectic Cardiff docks which dominated world export markets.

But trouble was brewing. Industrial Depression in Britain from 1925 had a major impact in South Wales and on Dowlais in particular. Welsh anthracite coal production had effectively peaked by 1913 and the industry had over-expanded. Coal production in the South Wales coalfields began to collapse, from an output of around 54 million tons (1913) to 35 million tons (1932). Dependant on coal, four major Welsh iron and steel works were forced to close between 1921 and 1936, including Dowlais. Cardiff’s docks, reportedly where the world’s first one-million-pound deal for coal had been struck at the Coal Exchange in 1904, went into sharp decline. Coal exports through the docks halved, from around 10 million tons per annum in 1913 to 5 million by 1932.

Working age male unemployment in the South Wales Valleys rocketed to 28% in 1925. Industrial relations plummeted and strike action spread. After the Wall Street Crash of 1929 and World Depression (1929-32), the jobless total rose further to 48% (1932). Mass emigration took place as a direct result: between 1925 and 1939 over 390,000 people left Wales. Working male unemployment in the country was still hovering around 15% in 1939. In the midst of this industrial decline and turmoil, members of Gareth’s family worked as mine safety supervisors keeping them serviceable during the many strikes and production freezes.

The Cardiff that Gareth was born into in 1936 had also suffered from the effects of the Depression years. A hunger march by coalminers to London in 1932 had taken place to protest falling living conditions. But Cardiff was far better than Dowlais, where King Edward VIII, visiting the area in November 1936 was shocked by the appearance of the local unemployed and their families. That year, unemployment in Dowlais was estimated at 73%, a catastrophe for the local community. The King famously remarked: “something should be done to get them (the coalminers) at work again”.

In 1936, after steel production had ceased at Dowlais, Samuel and family moved to the city. He transferred to the Guest Keen Baldwins East Moors Steelworks, close to Cardiff Docks. The East Moors site (1891-1978) was a vast industrial powerhouse, looming over the surrounding streets, with an annual output of 3 million tons of steel (1935). A light coating of red iron oxide dust often coated washing lines and buildings in its vicinity. By then, Samuel was a GKN technical expert. He led a team of four men, orchestrating the rolling of steel in searing heat, in charge of a state-of-the-art Sack stationary engine weighing at least 100 tons. It was an environment of extraordinary noise and high temperatures, so hot he was obliged to take salt tablets on most days. Periodically, there were industrial accidents and fatalities, caused by splashes of molten steel. Samuel nicknamed his morning walk from Roath to East Moors ‘the iron road’.

By the mid 1930s Cardiff was growing slowly, with a population of around 250,000. The Thomas family home was a terraced, slate-roofed late Victorian house in a respectable working-class area in Roath (Inverness Place). Then, as now, Inverness Place was well within walking distance of Roath Park, with its botanical gardens, well-heeled promenades and boating lake (opened 1894). Nearby lie the busy thoroughfares of Pen-Y-Wain Road, City Road and Albany Road. Inverness Place, bordered by Macintosh Place and Arabella Street, led up to the red-brick Anglican St Martin’s, Roath Church (opened 1901) on Albany Road. Coal fireplaces heated the houses and wrought iron railings adorned the house fronts, adjacent to every well-maintained porch. Each back garden was a narrow strip of grass enclosed by low slate walls.

In the 1930s, horse-drawn and motorised delivery vans delivered coal, dropped into a household chute. In pride of place, the front room of No 154 held a German Knauss upright piano (made in Koblenz in the 1890s), around which the Thomas family gathered.

Samuel and Catherine’s children were highly educated. This was a feature of skilled working-class aspiration in Cardiff of the era, where the parents’ hard work went hand in hand with Non-Conformist religious faith and the cultivation of a love of learning among their offspring. All Samuel and Catherine’s children would later work in education: their three daughters as primary and secondary school teachers, Gareth in higher education, teaching at university at degree level. Gareth’s early schooling was at Roath Park Infants School later in the war and (from 1947-1955) Cathays High School for Boys, then a grammar school.

Roath Park Primary School, Cardiff. Photo by Jaggery

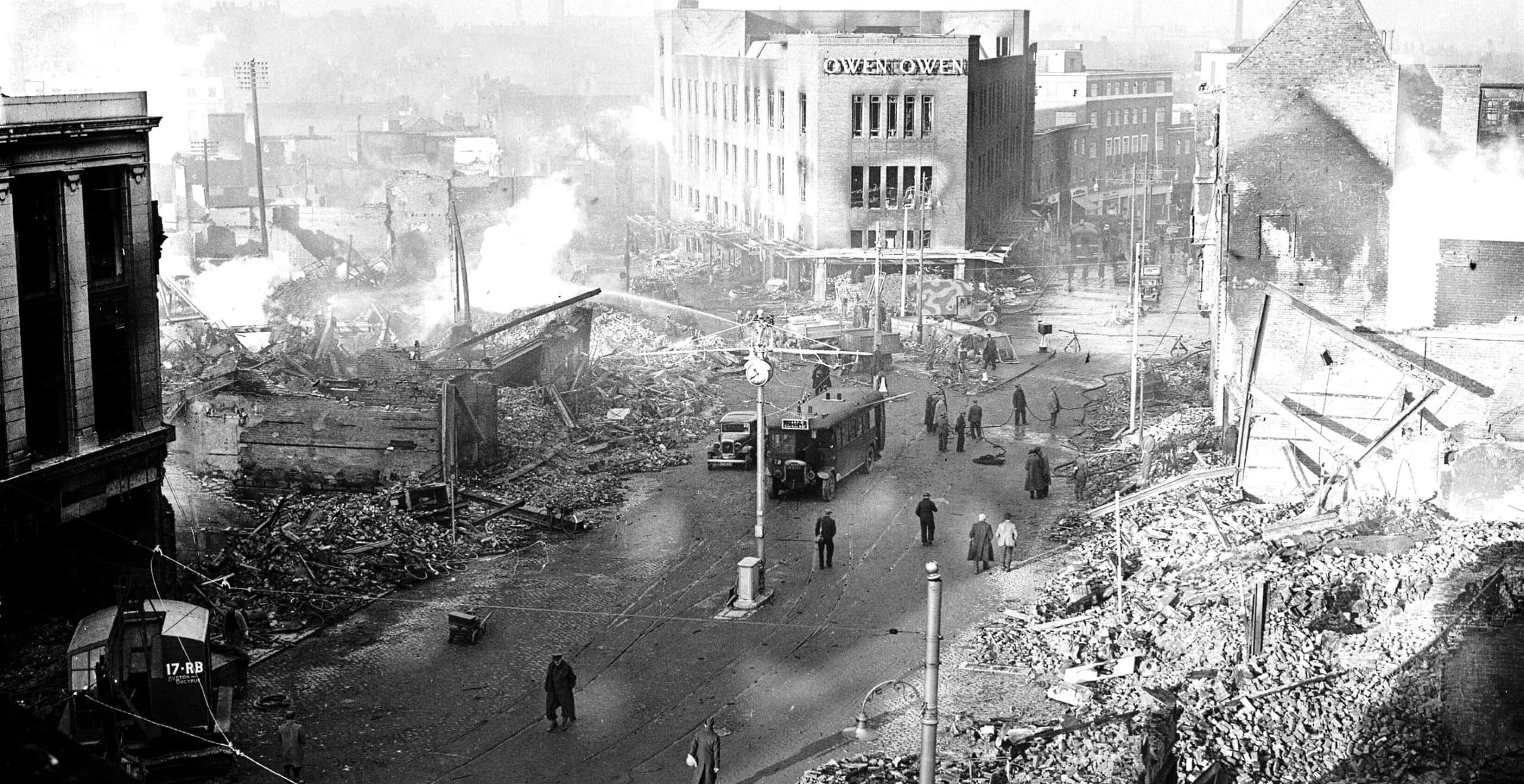

Gareth’s most powerful childhood memories were of the Cardiff Blitz (1940-1941). Cardiffians who experienced the Blitz were certainly marked by it. The danger of death and injury made memories of it intense, even for young children.

As the largest coal port in Britain, Cardiff was a predictable target for Hitler’s Luftwaffe. The city suffered four raids in July and August 1940, three major New Year night raids in January 1941, nine heavy attacks from February to April 1941 and two in May 1941. Further air raids on Cardiff took place during June-July 1941, June-July 1942, May 1943 and into March 1944.

Gareth had not yet started at Roath Park Infants School when war was declared on 3 September 1939, but he still remembered the delivery and assembly of an Anderson Shelter in the garden of Inverness Place. Anderson shelters were prefabricated corrugated steel and iron family shelters, named after the then Minster of War, John Anderson. 1.5 million were installed across Britain in the run up to the war. They were partially covered with soil and designed – in principle at least – to protect from all but a direct bomb hit. Inside the shelter were makeshift bunk beds and a lantern. All the house windows in Inverness Place were cross taped to prevent glass shattering from bomb blast.

Blackout curtains were rigged in every room. Gas masks were issued. A stirrup pump and bucket were placed in every hallway for basic firefighting. Each bath was painted with a level line in an attempt to conserve water supplies. Food rationing was introduced – in January 1940 – prompting long queues outside local shops.

Ironically, months of inactivity followed: the so-called ‘Phoney War’. Instead, in 1940, Prime Minister Winston Churchill’s Minister of Supply, Lord Beaverbrook, launched a nationwide publicity drive for the collection of aluminium pots and pans – metal for aircraft production – which were patriotically donated by Cardiff residents. Victorian and Edwardian iron railings and gateways were also later removed by council workmen, ostensibly for war purposes, and disappeared forever from local house fronts, public buildings and the boundaries of Cardiff’s parks.

In September 1940 the Blitz arrived in Cardiff, close to Inverness Place, with bomb damage inflicted on the corner of Angus Street and Albany Road, Roath.

Much worse was to follow. On the cold night of 2 January 1941 – Gareth was aged four and a half – 100 German bombers attacked Cardiff and its docks, part of the Luftwaffe’s attempt to smash Britain’s inward supply ports and surrounding heavy industrial production centres. The aircraft sent were Dornier Do-17, Heinkel HE-111 and Junkers JU-88 medium bombers, flying from bases in north western France.

For ten hours, from around 6.30pm, they dropped parachute flares to light their targets, then thousands of incendiaries and hundreds of high explosive bombs across the city, the docks and its environs. Buildings in Grangetown, Riverside and Canton were soon set alight by incendiaries. A parachute mine (‘land mine’ in popular parlance) blew the spire off Llandaff Cathedral. The raid killed 165, injured another 427, made 3,000 people homeless and destroyed almost 350 properties.

Children inside an Anderson shelter, Bournemouth, 1941. Photo TheBrit, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

At Inverness Place, after the sirens sounded, the family went down into the garden shelter. Gareth’s father Samuel worked through the raids at the steelworks. GKN did not cease operations under attack and steel production in Cardiff (including for shells, aircraft, tanks and steel helmets) continued flat out. As in the First World War, the East Moor Steelworks was at maximum capacity, producing the steel vital for British war production and eventual victory. Its aim: to outproduce its principal adversary, the German steel plants of the Ruhr, North Rhine, Westphalia.

Fortunately, the works escaped major damage during the Blitz (it was hit, in March 1944, but not extensively). Gareth saw his father – wearing a black steel helmet – opening the shelter door and blackout curtain to check on his family after coming back from the works. After a further heavy raid, in February 1941, Gareth was carried on his father’s shoulders along Inverness Place in time to see the burning roof of St Martin’s Church collapse into its interior.

Another night, Gareth, his mother and sister Enid did not make it to the Anderson shelter in time, after the air raid warning sirens suddenly wailed. They took cover under the stairs of the house whilst bombs whistled down and detonated nearby. To a small boy the noise was truly frightening. Several houses in the immediate vicinity of Inverness Place were hit or damaged.

Throughout the Blitz, Gareth, Enid and his mother could easily have been killed or seriously injured. He saw the probing beams of searchlights and heard the deafening barrages of British anti-aircraft guns firing in response (from Roath Park Recreation Ground). He felt his mother carrying him down to the shelter, holding a saucepan above his small head to protect him from falling shrapnel (either from exploded anti-aircraft shells or bomb splinters). Listening for the nightly, undulating drone of Luftwaffe aircraft engines, his mother asking: ‘is that a Mercedes?’ In the shelter, he heard the scratching of his sister Gwen’s ink pen, writing her Oxford University essays on German and French language and literature. When the All-Clear siren sounded, he noticed that the lavatories in nearby houses immediately started flushing as people left the shelters, and dogs began an incessant barking.

The British government clearly recognised the ordeal that port cities like Cardiff were enduring. On 12 April 1941, Prime Minister Winston Churchill visited the city as part of a wider morale-boosting tour of the Southwest. Pictures taken by his official photographer showed him driving that day- with raised hat – in an open car along Crofts Street, Roath, just south of Albany Road.

All his life Gareth reacted whenever he heard the spine-tingling sound of the All-Clear siren. It unfailingly brought him out in goose pimples, particularly on his forearms. He said it was because he was never sure what he might find when he emerged from the shelter. In any case, he used to smile and grimace whenever he heard the siren sound during the closing titles of the 1970’s comedy TV series ‘Dad’s Army’.

Gareth also had the common wartime experience of evacuation from home. He was sent for a time to his maiden Aunt Gwenllian’s house in Dowlais. He walked under a bright full moon, held by the hand until he reached her house in Regent Street. From the top floor bedroom, he could see the glow of burning Cardiff. Nevertheless, after the initial phase of the Blitz ended (on 10-11 May 1941), along with many other child evacuees, it was deemed safe enough for him to be sent home. This would prove a mistake.

Back in Roath, roaming the local bomb sites with his school friends, Gareth enjoyed collecting pieces of shrapnel and burning down the ends of sticks on the smouldering remnants of 1kg (2.2lb) German Thermite (magnesium) incendiary bombs. He watched barrage balloons – tethered by steel cables to deter low-flying aircraft – gently swaying in Cardiff’s parks. In a tree, he once saw the shredded remains of a young child known in the local area. Following a bicycle accident – he was sitting on the handlebars in front of his father when his foot caught in the wheel spokes – he was taken to hospital in Cardiff. Noticing wounded men covered by red blankets, he asked them who they were. They were friendly and said they were recovering, from Dunkirk.

After 11 May 1941 there was a lull in air attacks on Britain. Hitler was preparing to launch his grand strategic plan, Operation Barbarossa, the invasion of the Soviet Union (on 22 June 1941). Nevertheless, precision Luftwaffe air raids on Cardiff continued sporadically during 1942, 1943 and 1944. Gareth saw a crashed black German bomber guarded by armed soldiers. During one of the rare day raids, he had a close call in Roath Recreation Grounds, where an anti-aircraft (AA) battery had been positioned. He and other children happened to be playing nearby. The guns suddenly opened fire as German aircraft flew overhead. The children ran in all directions. The aircrew fired on the running figures, possibly seeing them as soldiers. Gareth witnessed the impact of machine gun fire churning up the grass. One child was injured. Gareth related that he felt real fear that day and that his mother was angry he had been playing there in the first place.

Though the family home escaped damage, wartime Cardiff was still unforgettable to a young child. Gareth had a Mickey Mouse faced gas mask and read ‘The Knockout’ and ‘Hotspur’ comics, purchased from local newsagents. His favourite serial was ‘Sexton Blake and the Rolling Sphere’ in ‘The Knockout’. He once said that everything in those days was about endurance, yet a confidence that Britain would always prevail. He described tightening the ‘snake-belt’ around his small waist because of the strict wartime food rationing in place across Britain.

From an early age he was told that exotic items such as bananas, sweets and chocolate were to be available again only ‘after the war’. The family prioritised their weekly butter ration for their working father. Gareth asked his father: ‘When will we win the war’? His father replied, ‘It all depends on the Eighth Army’ (then fighting in North Africa). His mother was obliged to queue, for hours, in Roath for the family’s ration book allowance (she had also done this during the First World War). He heard news of a local family evacuated from Cardiff to a rural Welsh farmhouse, all killed after a bomber jettisoned its ordnance. There was nothing left of the house.

There were other vivid recollections. One afternoon, in 1943 or 1944, Gareth’s mother took him to the Gaiety Cinema (opened 1910) on City Road. During the performance – newsreels and a film about Guadalcanal – an onscreen message advised the audience that a raid was in progress, and they should head for the shelter. Leaving the cinema, sheltering in its doorway with shattered glass underfoot, they saw broken overhead tram electricity lines sparking wildly.

Dambuster’s Raid, 16th May 1943

Dambuster’s Raid, 16th May 1943

At home, he heard Winston Churchill’s distinctive voice on the wireless in Inverness Place and the BBC Home Service bulletin on 17 May 1943 announcing the successful Dambusters Raid on the Ruhr dams in Germany. The next day -18 May 1943 – a retaliatory raid took place on Cardiff, during which houses on Pen-y-Lan Road and Cardiff Railway station were badly damaged. Around this time, he also remembered the visit on leave of his Canadian cousin, Flying Officer Edryd Jones (RCAF bomber pilot) to Inverness Place and the sight of his pilot’s wings, blue air force uniform and his strained face. It was hardly surprising – he was in the process of completing thirty bombing operations over Germany.

Throughout the war, the Cardiff docks were important to the wider Allied war effort, receiving and unloading food and munitions from the merchant convoys supplying Britain (arriving from Canada and the United States). They played a critical role during the Battle of the Atlantic in 1943, sustaining the nation despite the U-Boat Wolf Pack campaign and in unloading transports of American and Canadian troops and material arriving in the run up to the Normandy Landings on 6 June 1944 (D-Day).

In Roath Park, Gareth and other children saw a black American serviceman in an olive-green uniform. One boy asked him for sweets. The man pretended to search his pockets before kindly handing them a bar of chocolate, a rare luxury. Gareth was in the garden at Inverness Place when a single German twin-engined bomber (black in colour with crosses on its wings) roared directly overhead at extremely low level. Seconds later, two Spitfires swept past after it.

The last raid on Cardiff took place in March 1944. By war’s end 355 people had been killed (around 1,200 in total across Wales, primarily in Cardiff and Swansea) and over 500 seriously injured. At least 2,100 high explosive bombs had been dropped on the city. In 1944, Gareth remembered hearing the ‘V-Victory’ tone leading BBC wireless news broadcasts (the first four notes of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony and three dots and dash in Morse code) and BBC newsreader John Snagge’s announcement of the successful D-Day Landings (on 6 June 1944).

In 1945, playing in Roath Park gardens, he plucked out a newspaper floating in the stream. The headline told of events at a place called Belsen. In April, on the wireless, he heard of the death of Adolf Hitler and in August news of the dropping of atomic bombs on Japan. On Victory in Europe (VE) Day on 8 May 1945, the residents of Inverness Place held a street party which Gareth and his family attended. He also went down to Cardiff’s Civic Centre to see the celebrations. On another occasion, he joined a large crowd outside St John’s Baptist Church, northwest of The Hayes, watching a low victory flypast by Spitfires and Hurricanes. Some flew inverted, the pilots waving from their cockpits to the crowds below. Their flying helmets and faces were clearly visible.

In certain respects, the war may have underwritten Gareth’s childhood, but it did not dampen his natural wilfulness and youthful sense of adventure. At the age of ten (1946), this was startlingly demonstrated. His parents had decided to take a paddle steamer trip across the Bristol Channel from Cardiff to Weston-Super-Mare. These were a popular pastime and left regularly from Cardiff Docks. Gareth was unhappy not to be going as well and decided to follow them. He promptly stowed away on the next steamer to depart (a crewman even showed him around the engine room). He said his mother and father, strolling along the seafront at Weston, were astonished to see him approach them. Characteristically, he boldly slipped aboard again for the return trip.

In 1947, after leaving Roath Park Infants School, Gareth started his secondary education at Cathays High School for Boys, on New Zealand Road. Cathays (motto ‘Ymlaen’, ‘Forward’) was founded in 1903 as a grammar school with an Edwardian-style main entrance completed in 1930. At some point soon after he became ill with fever. He suffered several weeks of near insensibility at home (this was before the advent of the National Health Service in 1948).

Children found much to entertain themselves in post war Cardiff. Today’s health and safety culture was unknown. Each year on Bonfire Night (5 November) schoolboys in Roath lit ‘jumping jack’ fireworks which ignited and leapt about in the streets, randomly. Air rifles, pistols and catapults were commonplace. Other children had the habit of tying tin cans to the tails of cats. ‘That’s a ten canner’, the children would observe, as a cat ran past, unhappily.

As Gareth’s schooldays began (1947-1955), the family moved to 206 Albany Road, Roath, a quiet treelined avenue of Victorian red brick semi-detached houses. It was a clear step up from Inverness Place, in a solidly middle-class area. Gareth lived here with his family until his father’s death in 1957. He cycled to school and recalled ‘magical’ Christmases there. He listened to ‘Dick Barton’ on the BBC’s Light Programme and enjoyed regular trips to the seaside at Barry, Penarth and Porthcawl.

At Cathays High School, Gareth played cricket, rugby and acted in school plays. News sometimes filtered through about the Korean conflict (1950-1953) and he read how servicemen complained that it was a ‘forgotten war’. At weekends, Gareth ranged around the city with his friends. He often went to Roath Park, the Kardomah coffee shop on Queen Street, the Capitol Cinema and through the various covered arcades connecting St Mary’s Street, The Hayes and Queen Street. He played in the wooded slopes near Castell Coch above Tongwynlais, watched steam trains puff along the former Cardiff Railway and explored caves in Fforest Fawr.

Cathays High School, Fifth Form 1952. Gareth is front row, extreme left

Cathays High School, Fifth Form 1952. Gareth is front row, extreme left

In 1949 he saw the prototype Bristol ‘Brabazon’ airliner take off near Bristol (Gareth saw it from a train with his schoolfriends). The gleaming Brabazon was an eight-engined turboprop aircraft, with the potential to revolutionise the air passenger market. A series of failures meant that it was never put into production, and it was cancelled in 1953. It was replaced by the De Havilland Comet airliner as the last post war hope of British aviation. At an air show at RAF St Athan, Glamorgan, Gareth and his father also witnessed the crash of an RAF Harvard trainer whilst performing a ‘falling leaf’ acrobatic manoeuvre. The squadron leader piloting it was killed.

Aged fifteen, he travelled with a school group to visit the Festival of Britain (1951) on London’s South Bank. The Festival was a hugely popular showcase of British achievement, a celebration injecting national optimism after the rigours of the war. The school group stayed at the Clapham South Deep Shelter and he marvelled at the futuristic Skylon sculpture and the Dome of Discovery. One lunchtime, he spread butter and jam on the same piece of cake. The master in charge of the group rebuked him for such extravagance (food rationing in Britain persisted until 1954). He asked local residents (whom the Welsh schoolboys called ‘cockneys’) for a glass of water. A woman and her family let him into their house, asked where he was from and told him how smart he looked in his Cathays uniform. Whilst thanking her for her generosity he couldn’t help noticing how poorly furnished the house was and that the floor lacked tiles or carpets.

Gareth and his family also watched the Coronation of Queen Elizabeth II in 1953 in 206 Albany Road on a new television set (with a flickering black and white picture). Neighbours were invited in to watch from the street party held outside. Gareth’s Cardiff schooldays left him with a love of literature and socialising in the city centre. He tried other interests, pushing the boundaries by attending a greyhound race meeting in Cardiff and drinking experimental pints of bitter, both something his father – a strict Congregationalist teetotaller – discovered and sternly disapproved of. In the sixth form, Gareth and a friend were once walking near their school, then as now adjoined by Maindy Barracks and (in the 1950s) a firing range. A vehicle pulled up alongside them and, unceremoniously, they were picked up by the Royal Military Police (RMP). Despite their protests, they were taken to the Barracks guardroom. An officer suggested they were absconding National Service conscripts. Eventually, they were believed and released – without apology – back to their classroom.

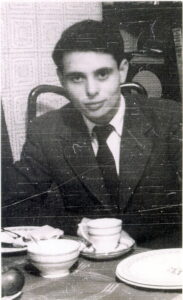

Gareth, Cathays High School Cardiff, Sixth Form,1954

Gareth, Cathays High School Cardiff, Sixth Form,1954

As Gareth neared the end of his schooldays in 1954, his father Samuel had a stroke. His speech was affected, although his mobility later improved. He died in 1957. Just after leaving school, Gareth and a schoolfriend took a working holiday on a farm in Normandy. The scars of the 1944 invasion were everywhere and he noticed the many destroyed pillboxes. He also took a temporary job at Cardiff Railway Station, unloading iced boxes of fresh fish, a demanding task for a teenage grammar schoolboy. All the same, the job had its compensations: he was given the chance to drive a shunter steam locomotive for a short distance, a boyhood dream.

With schooldays over, Gareth prepared for his obligatory National Service and in 1955 left the city of his birth. But he always returned.

Because Cardiff had made him.

After completing his National Service with the Royal Welch Fusiliers (1955-1957), Gareth Thomas moved to London where he worked in commerce before graduating from London University. He was married with two children and had a thirty-year career as a History and Economics lecturer, firstly at Southwark College, then Hatfield Polytechnic and the University of Hertfordshire. He retired as a University Principal lecturer in 1997 and lived in St Albans, Hertfordshire. He died at Watford Peace Hospice in August 2021.

By Ronan Thomas

Published 14th July 2023