On Tuesday 29th October 1929 the Wall Street Crash caused a cataclysmic chain of events which affected nearly every country across the globe. The Great Depression, also known as ‘The Slump’ infiltrated every corner of society, affecting people’s lives between 1929 and 1939 and beyond. In Britain, the impact was enormous and led some to refer to this dire economic time as the ‘devil’s decade’.

This economic depression occurred as a direct result of the impact of a stock market crash on Wall Street in October 1929. The American economy in the 1920’s was capitalising on the post-war optimism, leading many rural Americans to try their luck in the big cities with the promise of prosperity and wealth. ‘The Roaring Twenties’ as it was known was experiencing a boom in the industrial sector, life was good, money was flowing and excess and opulence was the name of the game, characterised by fictional figures such as ‘The Great Gatsby’.

Unfortunately, the prosperity experienced in the big American cities was not replicated in the rural communities, mainly due to overproduction in agriculture which caused financial difficulty for American farmers throughout the ‘Roaring Twenties’. This would end up being one of the key reasons for the subsequent financial crash.

In the meantime, back in the ‘big smoke’ (aka London) people began to play the stock exchange and the banks were using people’s own personal savings to increase profits. Speculation was rife with people jumping onto the fever of economic optimism that was sweeping the nation.

Industry ranging from iron and steel, construction, automobiles and retail was booming in the 1920’s, leading more and more Americans to invest in the stock market. This led to an enormous increase in borrowing in order to purchase the stock in the first place. By late 1929, this borrowing and buying cycle was out of control, with lenders giving up to two thirds more than the value of the actual stock; by this time around $8.5 billion dollars was on loan. This figure was significantly larger than the amount of money actually circulating in the country at the time.

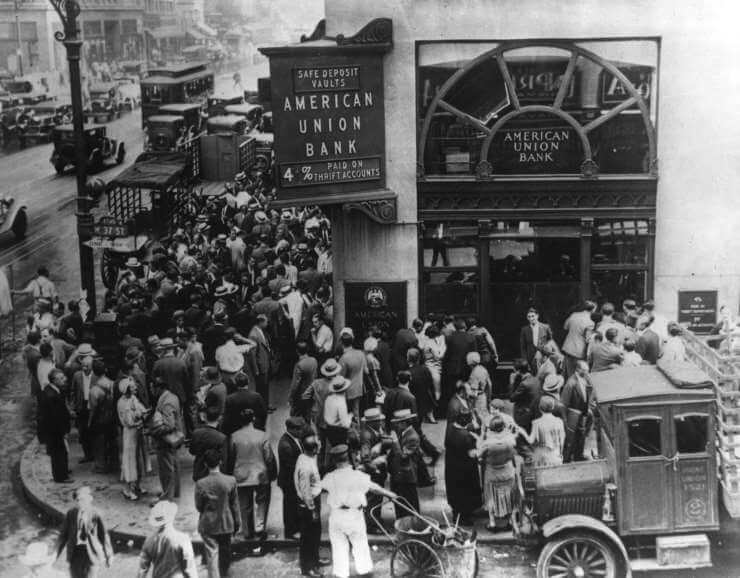

By 1929 the buying and borrowing cycle proved too much and the returns on the share prices began to fall. The immediate reaction was for many to start selling their shares. Before too long, this collective sense of panic led to large scale withdrawal: people were subsequently forced into an untenable situation, unable to repay loans. The economy was teetering on the edge and it was only a matter of time until it fell into economic freefall. In 1929, this is exactly what happened.

The Great Depression started in the United States causing an enormous reduction in the worldwide gross domestic product, which fell in the period from 1929 to 1932 by fifteen percent. The impact was widespread and the most severe depression ever experienced in the western world, causing high levels of unemployment for years afterwards. It proved to be not only an economic catastrophe but also a social one.

The American crash caused a domino effect, encapsulating widespread financial panic, misjudged government policy and decline in consumerism. The gold standard which was inextricably linked to most countries across the world through the fixed exchange rates helped to transmit the crisis to other countries. In order to deal with such a crisis, big changes in economic policy and management needed to be introduced.

For Britain and Europe the fallout was extensive; with the American markets taking the hit, the demand for European exports declined. This ultimately had the effect of reducing European output which resulted in large scale unemployment. Another major impact of the downturn was based upon the lending which had been taking place for years. The American lenders responded by recalling their loans and American capital, leaving Europeans with their own currency crisis. One of the most obvious solutions, as adopted by Britain in 1931, was to leave the Gold Standard.

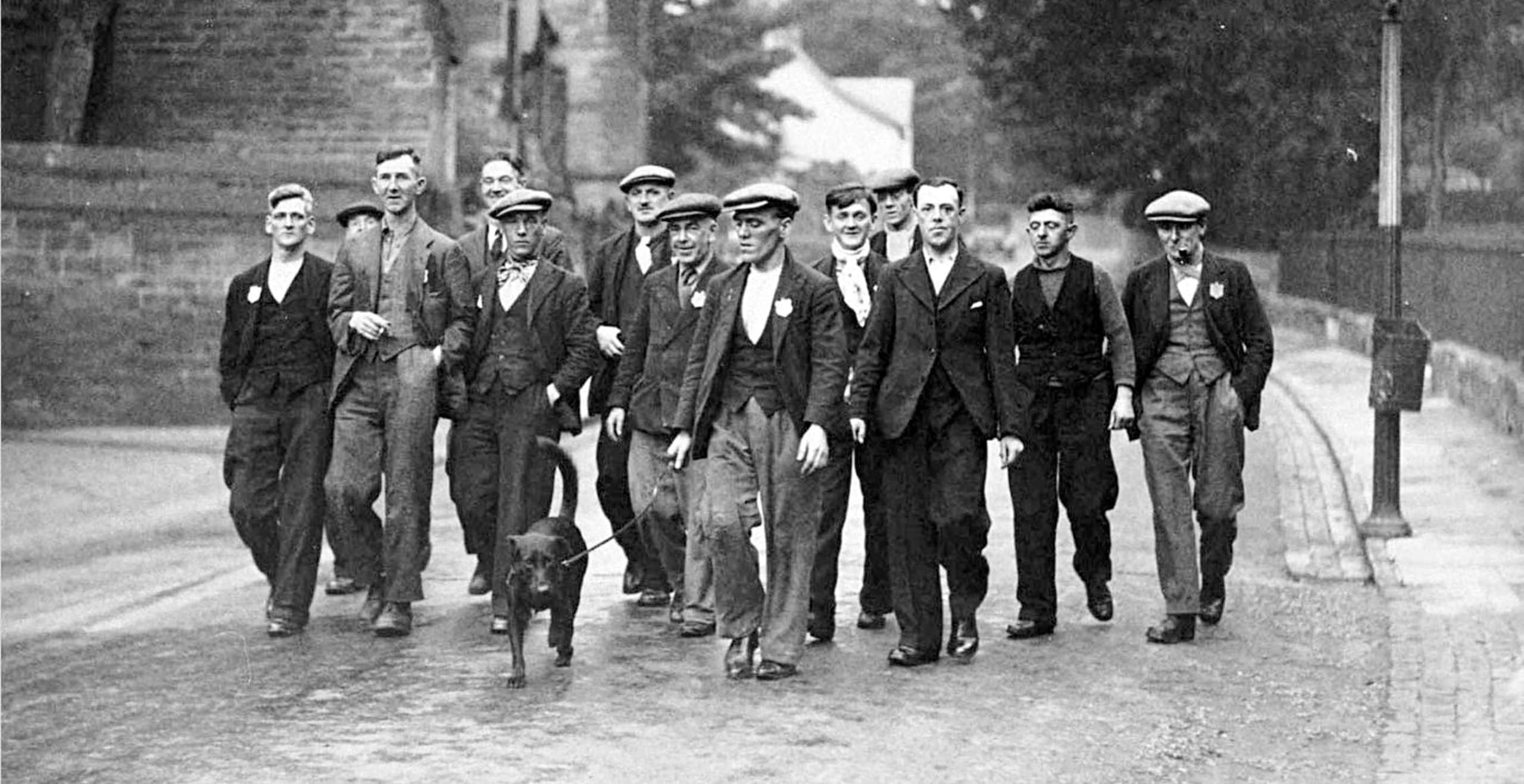

Britain was functioning as a major exporting country and so when the crisis hit, the country was badly affected. In the first few years after the crash, British exports fell by half which had a disastrous effect on employment levels. The numbers of unemployed in the years that followed was astronomical, rising to around 2.75 million people, many of whom were not insured. The high levels of unemployment and lack of business opportunities were not equally felt across Britain, with some areas escaping the worst of it, whilst at the same time others suffered terribly.

Industrial areas such as southern Wales, the north-east of England and parts of Scotland were greatly affected due to the staple industries of coal, iron, steel and shipbuilding experiencing the worst of the economic hit. Jobs subsequently suffered and the areas which had flourished in the industrial revolution were now suffering badly.

The number of unemployed had reached the millions and the impact for many was starvation. Men were left unable to provide for their families and many resorted to queuing at soup kitchens. This was recorded by a government report, highlighting that around a quarter of the British population were barely existing on a poor subsistence diet. The result was increased cases of child malnutrition resulting in scurvy, rickets and tuberculosis. The economic crisis had turned into a social one. The government needed to act fast.

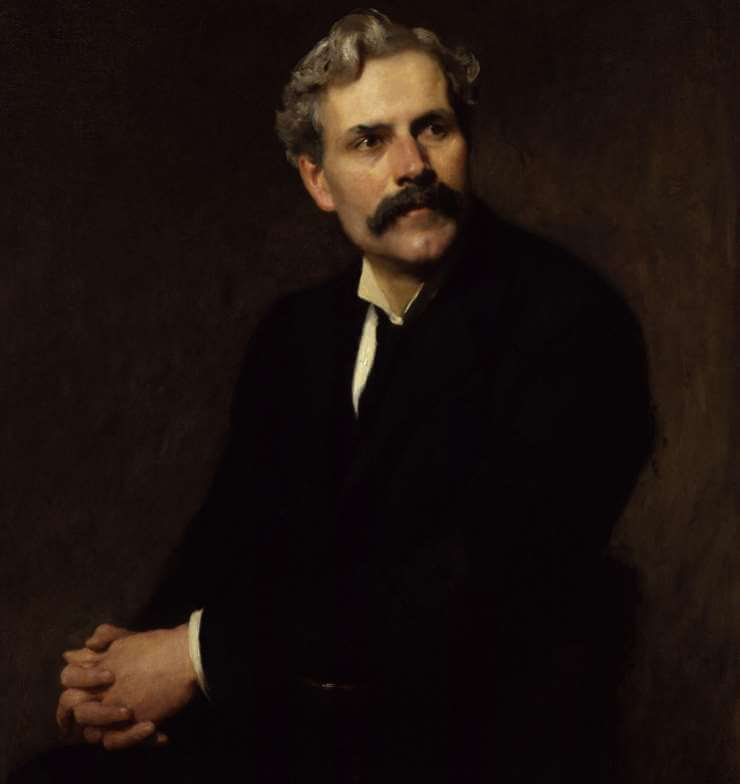

In 1930 a small ministerial team was formed to tackle the most pressing issue, that of unemployment. This was led by J.H Thomas who was a leading figure in the railway union, as well as George Lansbury and the infamous character Oswald Mosley (the man who established Britain’s Fascist Party). In this period, government spending had gone through the roof; for Mosley, the policy-making was too slow and he presented his own plan called the Mosley Memorandum. This was subsequently rejected.

Moderates, including MacDonald and Snowden had enormous conflict with the more radical proposals put forward, and eventually a fifteen member Economic Advisory Council was introduced. This was formed of industrialists and economists such as the famous Keynes, who would collectively come up with more creative solutions to the current crisis. In the meantime, the government was failing to win support and seemed doomed to fail at the next General Election.

Meanwhile, in Europe the banks began to collapse under the economic strain, leading to further British losses. For British politicians, spending cuts seemed like the natural solution and in July 1931 the May Committee, upon reporting a deficit amounting to around £120 million, made the suggestion of a twenty percent decrease in unemployment benefit. A political solution for some but for those living below the poverty line, hunger and penury beckoned.

A ‘run on the pound’ led to a major withdrawal of funds and investment from foreign sources who were fearing the worst. This led to almost one quarter of the Bank of England’s gold reserves being used. The situation looked more ominous with the Cabinet still split on issues relating to public spending. By 23rd August, despite his success in winning the vote to cut back on public spending, MacDonald resigned and the following day a National Government was formed.

A month later elections were held, resulting in a Conservative landslide victory. The Labour Party, with forty-six seats, was badly damaged by the mismanagement of the crisis and despite MacDonald continuing as Prime Minister in 1935, the era was now politically dominated by the Conservatives.

Britain in late 1931 began a slow recovery from the crisis, partly prompted by its withdrawal from the Gold Standard and devaluation of the pound. Interest rates were also reduced and British exports were starting to appear more competitive on the global market. It would not be until several years later that the impact on unemployment finally began to take effect.

In the south, recovery occurred sooner, largely as a result of a strong construction industry with booming levels of house production aiding the recovery. For the worst affected areas, the progress would be much slower, despite government attempts at reforming and developing the areas with loans to shipyards and road building projects.

The Great Depression continued to wreak havoc on many people’s lives across the globe and what had started as a decade of economic optimism ended with widespread financial ruin and despair. The Great Depression infiltrated the lives of a generation and those beyond it, with tough lessons needing to be learnt. It remains one of the most pivotal moments of economic history, as a warning to all, never let it happen again.

Jessica Brain is a freelance writer specialising in history. Based in Kent and a lover of all things historical.

Published: 29th December 2018.