“Jarrow as a town has been murdered”, were the words ushered by MP Ellen Wilkinson when she addressed a crowd in Hyde Park in 1936. She had participated in the march at various stages, beginning in Jarrow on 5th October and concluding the arduous journey in London on 31st October 1936.

Wilkinson had immediately felt a strong empathy towards the plight of the Jarrow marchers. Although not particularly well-received and with a refusal to meet them by the Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin, Wilkinson presented the town’s petition to the House of Commons on 4th November. The response was minimal and the workers were forced to return home dejected.

The Jarrow March was a failure. A failure for those men desperate for employment, desperate for change and seeking acknowledgement of their plight. The Jarrow March may not have achieved its aims but it turned out to be a crucial turning point in the social attitudes of Britain in the following decades.

Jarrow is a town nestled in the North East of England on the banks of the River Tyne. Historically, the town had been reliant on the coal industry as its main source of employment. The work was difficult and extremely dangerous; the workers were risking their lives every day, working in terrible conditions and with little to show for it.

In 1851 a shipyard was established at Jarrow, changing the main source of employment from the coal industry to ship building. Local men worked in Palmer’s shipyard producing around 1,000 ships in the eighty years it was in operation. Jarrow’s shipyard became the largest of its kind in the country, producing warships for the Navy and providing high employment levels for the men in the surrounding area.

Palmer’s remained in high demand well into the First World War when the local shipyard produced Britain’s warships such as HMS Resolution. Even after the war, the shipyard continued its production and maintained manageable levels of profit, however the 1920’s brought a new array of problems.

Britain had previously enjoyed a monopoly on the shipbuilding trade back in the 1890s, but as more countries continued to develop their economies, fewer would turn to Britain for its shipbuilding expertise. A further blow to the business occurred when Palmer’s management overestimated the future demand and need for investment. This proved to be a disaster for the company with bookings down and investment going to waste. The 1930s Great Depression was the final straw which led to the downturn of profits and forced the eventual closure of the yard in 1934.

An American entrepreneur called T.Vosper Salt proved to be a crucial figure in giving hope to the people of Jarrow in these dark times. He was interested in investing in a steel site as he believed the steel industry was on the verge of a boom. He began to discuss his proposal seriously with the British Iron and Steel Federation (BISF). The BISF report on the possibility of a steelwork plant in Jarrow had a mixed reception with some members asking for any capital for the project to be withheld. This caused great anxiety for the men and women of Jarrow who were looking to the new steel plant as a way out of unemployment and abject poverty.

Baldwin gave a speech in an attempt to reassure the people of Jarrow that any steel works proposals were under genuine consideration, although his optimistic tone amounted to nothing. Salt and the other investors eventually withdrew as the project began to appear more and more unviable.

Ellen Wilkinson was vocal in her support for the town. The lack of response from the House of Commons and lack of empathy for those in poverty in Jarrow was the final straw for those men whose own lives and those of their loved ones were on the line. Action needed to be taken.

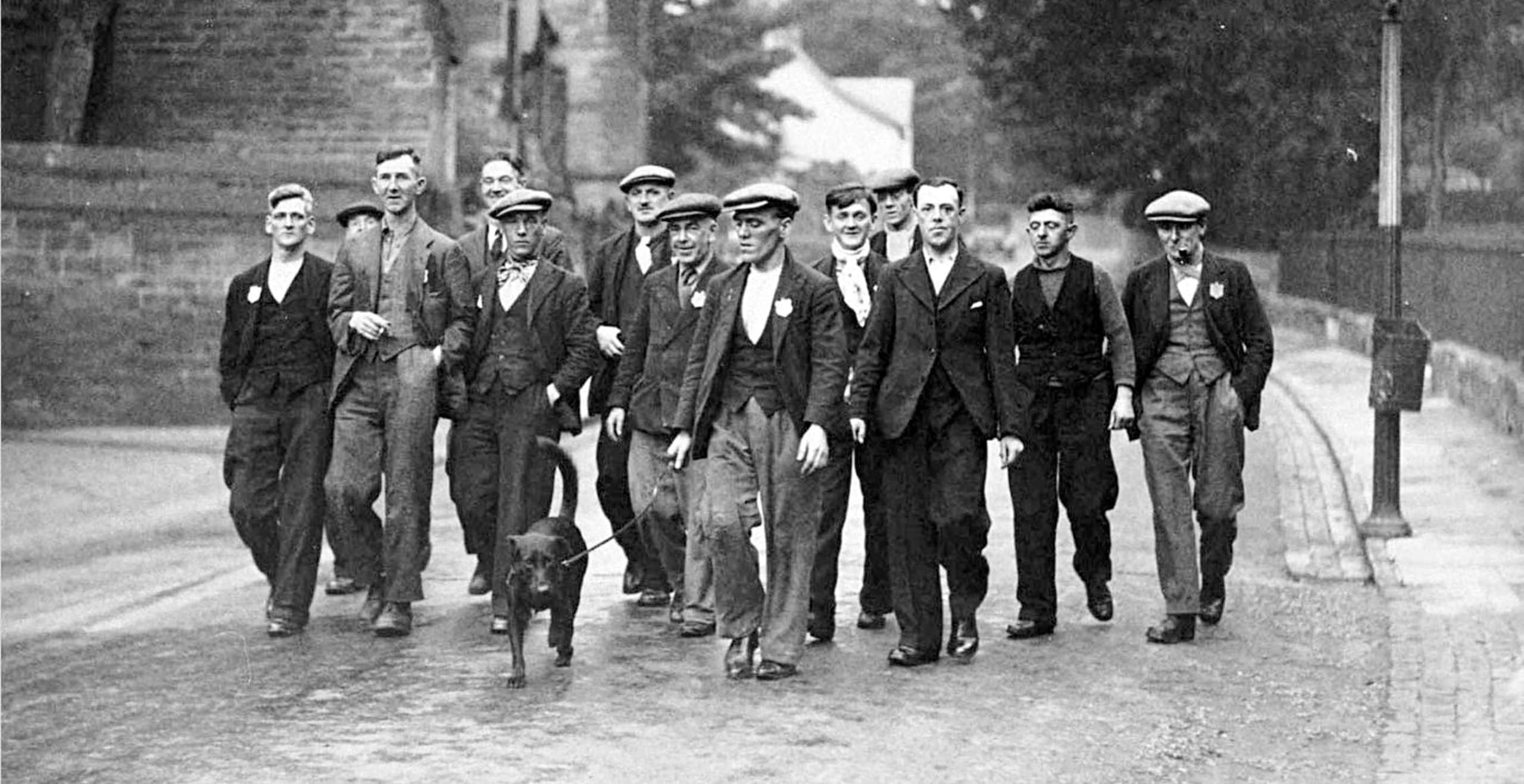

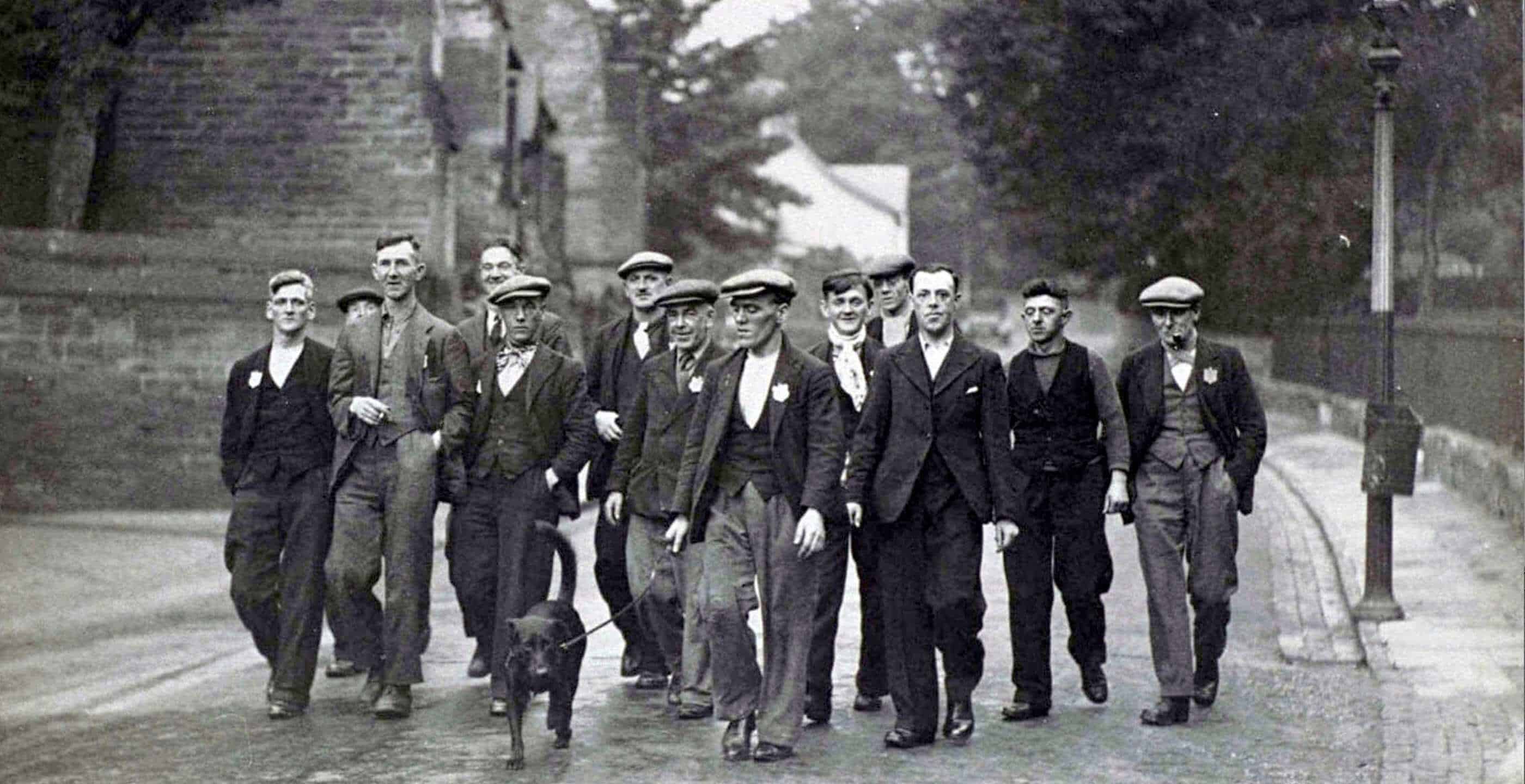

On Monday 5th October 1936, 200 fit men who had been selected for the march set off, leaving Jarrow to crowds cheering them on, holding banners and encouraging their fellow townspeople. Over the next 26 days the men toured the country, taking scheduled rests and passing through towns such as Harrogate, Mansfield and Northampton.

Eventually on Sunday 1st November the marchers proceeded to Hyde Park where a rally was quickly arranged. Ellen Wilkinson on the 4th November handed the petition to the House of Commons with over 11,000 signatures. The result, a meek discussion on the situation in Jarrow, their sympathies heard but not addressed, the men after weeks of walking, preparation and months of living below the bread line returned to Jarrow the next day disheartened.

The situation in Jarrow did not change remarkably. That being said the Jarrow March left an indelible mark on Britain’s protest culture, it shed light on the ability of ordinary people to stand up for what they believed in. As attitudes began to evolve so too did the view of people as influential political actors and the need in a democracy to have the right to protest.

The Jarrow March continues to be remembered 81 years later, a mark of the ordinary man and his right to be heard. Britain’s democracy continues to uphold this legacy today.

Jessica Brain is a freelance writer specialising in history. Based in Kent and a lover of all things historical.

Published: 27th September 2021.