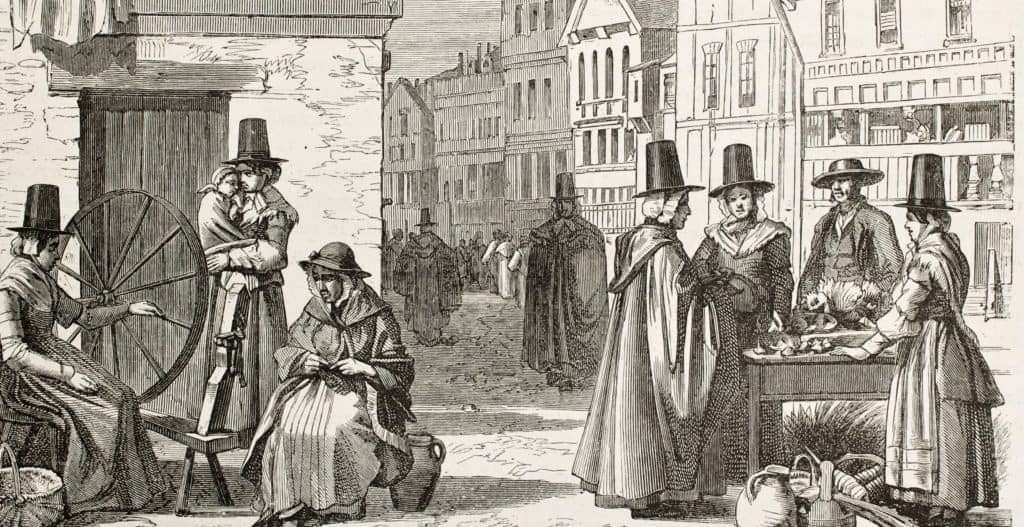

Wales is a country steeped in tradition. Even the Methodist revival in the 18th century, whose stern Puritanism banished the ancient Celtic traditions, was unable to stamp out all remains of their traditions.

Today the old tales are kept alive by the Welsh speakers. There are an estimated 600,000 of them and the numbers are increasing. Traditional Welsh culture has been kept alive by the popularity of the Royal National Eisteddfod, a ceremonial gathering of musicians, poets and craftsmen.

In the late 19th century children were not encouraged to speak Welsh in school. If they did so, they were punished by having a piece of wood called a ‘Welsh Not’ hung around their neck.

The Welsh Folk Museum at St. Fagans in Glamorgan has many folklore pieces. The carved wooden spoons, called ‘Love Spoons’, were carved by young men while they visited their sweethearts. The carving of these spoons apparently was encouraged by the young lady’s father as it ensured that the young man’s hands were kept occupied! The spoons are beautifully carved and combine both ancient Celtic designs and symbols of affection, commitment and faith.

The Welsh Folk Museum at St. Fagans in Glamorgan has many folklore pieces. The carved wooden spoons, called ‘Love Spoons’, were carved by young men while they visited their sweethearts. The carving of these spoons apparently was encouraged by the young lady’s father as it ensured that the young man’s hands were kept occupied! The spoons are beautifully carved and combine both ancient Celtic designs and symbols of affection, commitment and faith.

Possibly the most important record of early myth, legend, folklore and language of Wales is contained within The Mabinogion . The Mabinogion is a collection of eleven stories translated from medieval Welsh manuscripts including tales of pre-Christian Celtic mythology and traditions. Although translated from medieval text, the tales record characters and events from several centuries earlier, including mention of a revolting Roman Emperor and even reference to the Arthurian legend.

Mining has long been a staple occupation in Wales and there are many superstitions and traditions associated with it.

The Romans were the first to extensively mine for gold and lead. One of the largest lead mines was at Cwmystwth where in the 18th century silver was also mined. Dolaucothi near Pumpsaint is the site of a Roman gold mine, the only one in Britain. The gold near the surface was exploited by open-cast working and the deeper ore was reached underground by galleries. The galleries were drained by a timber water-wheel, part of which can be seen in the National Museum in Cardiff. Underground coal mining began in Wales over 400 years ago.

In the past, superstitions were rife in all the coal mining communities and were always heeded!

In South Wales, Friday is associated with bad luck. Miners refuse to start any new work on a Friday and pit-men always stayed away from the mines on Good Friday throughout Wales.

In 1890 at Morfa Colliery near Port Talbot, a sweet rose-like perfume was noted. The perfume was said to be coming from invisible ‘death flowers’. On March 10th half the miners on the morning shift stayed at home. Later that day there was an explosion at the colliery and 87 miners were buried alive and subsequently perished in the disaster.

A robin, pigeon and dove seen flying around the pit head foretold of disaster. They were called ‘corpse birds’ and were said to have been seen before the explosion at Senghennydd Colliery in Glamorgan in 1913 when 400 miners died.

Many precautions against bad luck were taken. If a ‘squinting’ woman was met on the way to work, the miner would go back home again. The women-folk also tried to banish any bad luck. When lots were being drawn for a position at the coal face, the miner’s wife would hang the fire-tongs from the mantle-piece and put the family cat in the un-lit oven!