In March 1987, the ferry The Herald of Free Enterprise sank off Zeebrugge with the loss of 188 lives. This great tragedy occurred because the roll-on/roll-off ferry had sailed with its bow doors open, a court subsequently discovered.

While many have heard of the disaster of the Herald, far fewer remember the loss of the Princess Victoria ferry 34 years earlier in the great storm of January 1953. On that occasion 133 people died, making it the UK’s greatest post-war maritime disaster at that time.

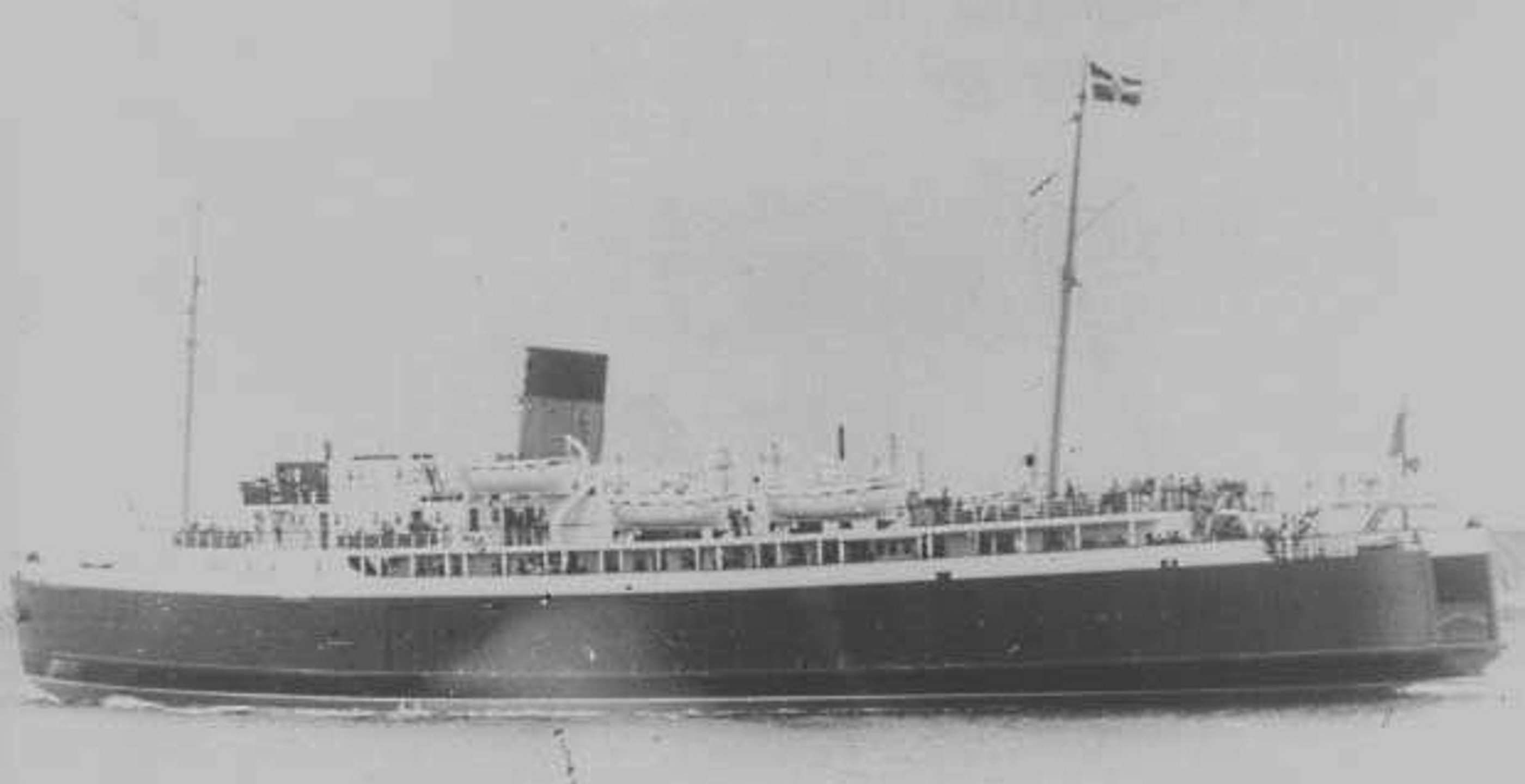

The Princess Victoria, built in 1947 by shipbuilders William Denny and Brothers of Dumbarton, was the fourth ship of that name to provide ferry services around the UK. An earlier Princess Victoria had been sunk in the Humber estuary during World War II.

The latest Princess Victoria was one of the first of a new type of ferry to be used in UK and European waters. Weighing in at 2694 tons, the ferry could carry up to 1500 passengers as well as cars and lorries. The ferry was designed to serve between Stranraer in Scotland and Larne in Northern Ireland and was equipped with the most up-to-date navigational equipment.

Most importantly from the perspective of passengers and freight carriers, the Princess Victoria was one of the latest drive on/drive off vessels, of the type that would come to be known as ro-ro (roll on/roll off) ferries. Drivers drove onto the cargo deck of the ship via a ramp at the stern, the deck then being closed off by two doors about 5’ 7” (1.7m) in height that acted as a bulwark, but not a seal, against the sea.

Anyone who has made a ferry trip across the North Channel between Stranraer or Cairnryan and Northern Ireland will know what a pleasant experience this is in good weather. The conditions at sea can change dramatically and suddenly in this part of the world, but the ferry companies and their passengers now benefit from the latest in satellite technology to provide ongoing forecasts.

On 31st January 1953, long before satellites, the Met Office and the BBC Shipping Forecast provided the best information for vessels at sea. The forecast that day reported that a deep depression to the north-west of Scotland would bring gale-force north-westerly winds right across the path of the Princess Victoria, due to begin her regular crossing from Stranraer to Larne at 7.45 that morning.

Her captain was James Ferguson, who had worked on the crossing for 17 years. The Princess Victoria also carried a crew of 49 to 51 crew – sources vary – and 128 passengers – again, accounts vary. This is perhaps not entirely surprising since regulations requiring a full manifest of passengers on ferries have only become mandatory fairly recently. During bad weather conditions, some passengers booked onto ferries simply didn’t turn up.

The Princess Victoria set off on the regular route along Loch Ryan with her passengers, a few vehicles and 44 tons of cargo on board. Even in the best weather, progressing from the relatively sheltered Loch Ryan to open sea can be felt by passengers on board a ferry. That fateful morning the Princess Victoria left the loch to be met with a full gale-force storm that was already lashing the sea into 30 foot (9m) waves. The original depression forecast by the meteorologists had deepened due to a smaller secondary depression on its leading south-eastern edge.

As the bow of his vessel nose-dived into a trough of one of the immense waves, throwing passengers and crew about, Captain Ferguson realised that if he attempted to follow the south-westerly heading to Larne the ship would be beam-on to these massive waves with potentially catastrophic consequences. There was only one option – to attempt to return to Loch Ryan.

This was in itself a dangerous manoeuvre, since it would put the ship first broadside and then stern-on to those terrifying waves. The engines were slowed as the vessel prepared to turn to starboard for the return. Corkscrewing into the trough of a wave, the vessel managed to complete the turn but was pooped – smashed on the stern by the power of the waves – so that the car deck doors were damaged beyond repair and water flooded the deck.

The immediate issue was to prevent any more water entering the stern. Bringing his ferry back about to head into the storm again, Ferguson then attempted to go astern into Loch Ryan, using the bow rudder. When the rudder couldn’t be released, the vessel hove to (attempted to maintain position) off the entrance of Loch Ryan. David Broadfoot, the ferry’s radio operator, used morse code to call for tug assistance and lifejackets were issued.

By 10.32 am, with the ferry listing and drifting sternwards down the North Channel, Broadfoot sent out a general SOS. Worsening weather conditions brought winds of 120 mph with flurries of sleet and snow reducing visibility to nil at times. Captain Ferguson continued to calm the passengers despite the dreadful circumstances.

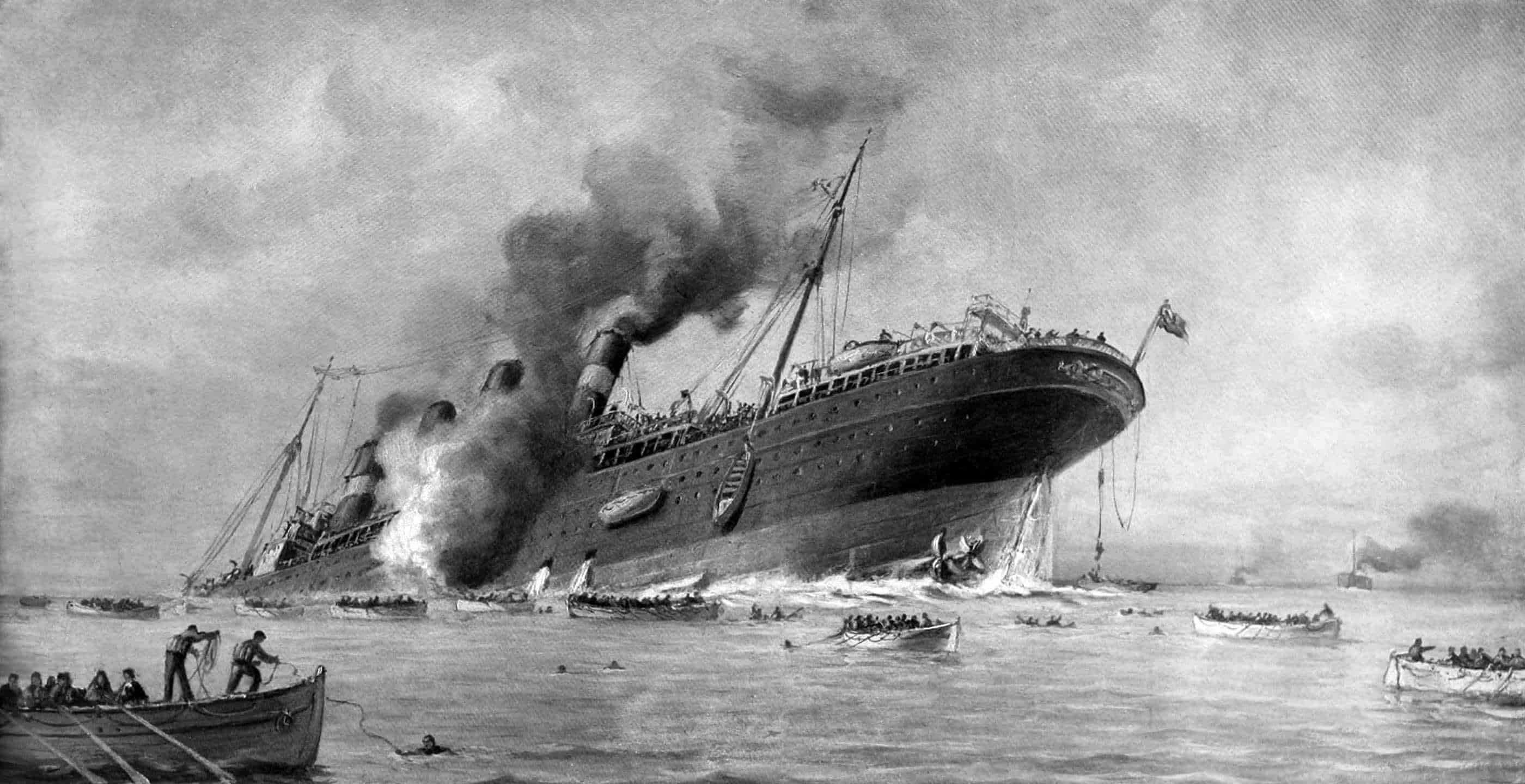

RNLI Lifeboats were launched from Portpatrick and Donaghadee and the destroyer HMS Contest set off from the Clyde to assist shortly after 11 am. At 13.58 the Princess Victoria rolled onto her beam ends and the order to abandon ship was given. Her last reported position was five miles east of the Copeland Islands just south of the entrance to Belfast Lough.

In fact the true location of the ferry was five miles to the north of the reported position. This, along with the atrocious conditions, damage to search vessels and the demands of numerous other SOS calls meant that the Princess Victoria foundered before any rescue vessel could reach her.

When it was clear the ferry was about to go down, an attempt was made to get passengers into the safety of the ferry’s lifeboats. However, the vessel was listing so badly that while the starboard boats were in the sea but inaccessible due to the intensity of the storm, the lifeboats on the port side could only be lowered into the water as the ship was actually going down.

It was at this moment, just as passengers were entering the lifeboats, that the Princess Victoria capsized. Several commercial vessels from Belfast Lough, the Orchy, the Lairdsmoor, the Eastcotes and the Pass of Drumochter had set off in a desperate rescue attempt. They, along with the two lifeboats, the HMS Contest and a salvage vessel, the Salveda, were initially heading for the last location provided by the ferry. It was only when the Orchy encountered wreckage that the ferry’s true location was discovered.

Just 44 people survived the loss of the Princess Victoria. The Captain and his officers did not survive, nor did any of the women and children on board. David Broadfoot, who had courageously kept contact from the radio room until the sea flooded it, was awarded a posthumous George Cross. The captains of the merchant vessels were made members of the Order of the British Empire. Officers of the HMS Contest were awarded the George Medal for their bravery in entering the water to assist the survivors.

Among the dead were the Deputy Prime Minister of Northern Ireland and the MP for North Down. The final death toll from the great storm in Britain, the Netherlands and Belgium was over 500, the foundering of the Princess Victoria being the largest single loss of life.

While the news was spreading of events in the North Channel, the inhabitants of Orkney feared a similar tragedy for one of their own steamers. The Earl Thorfinn, a conventional ferry, had gone missing at 9am on the same day, somewhere between the two of the islands of Orkney, Stronsay and Sanday. The vessel had thankfully found refuge in Aberdeen 160 miles to the south after her master, Captain Flett, managed to run with the storm despite the massive following waves that threatened to overwhelm his ship.

Although separated by 20 miles of sea, there have always been strong links and a sense of community between the coastal towns of south west Scotland and those of Northern Ireland. Today, the tragic story of the Princess Victoria is commemorated in several locations, including a very moving memorial at Portpatrick in Scotland.

Miriam Bibby BA MPhil FSA Scot is a historian, Egyptologist and archaeologist with a special interest in equine history. Miriam has worked as a museum curator, university academic, editor and heritage management consultant. She is currently completing her PhD at the University of Glasgow.