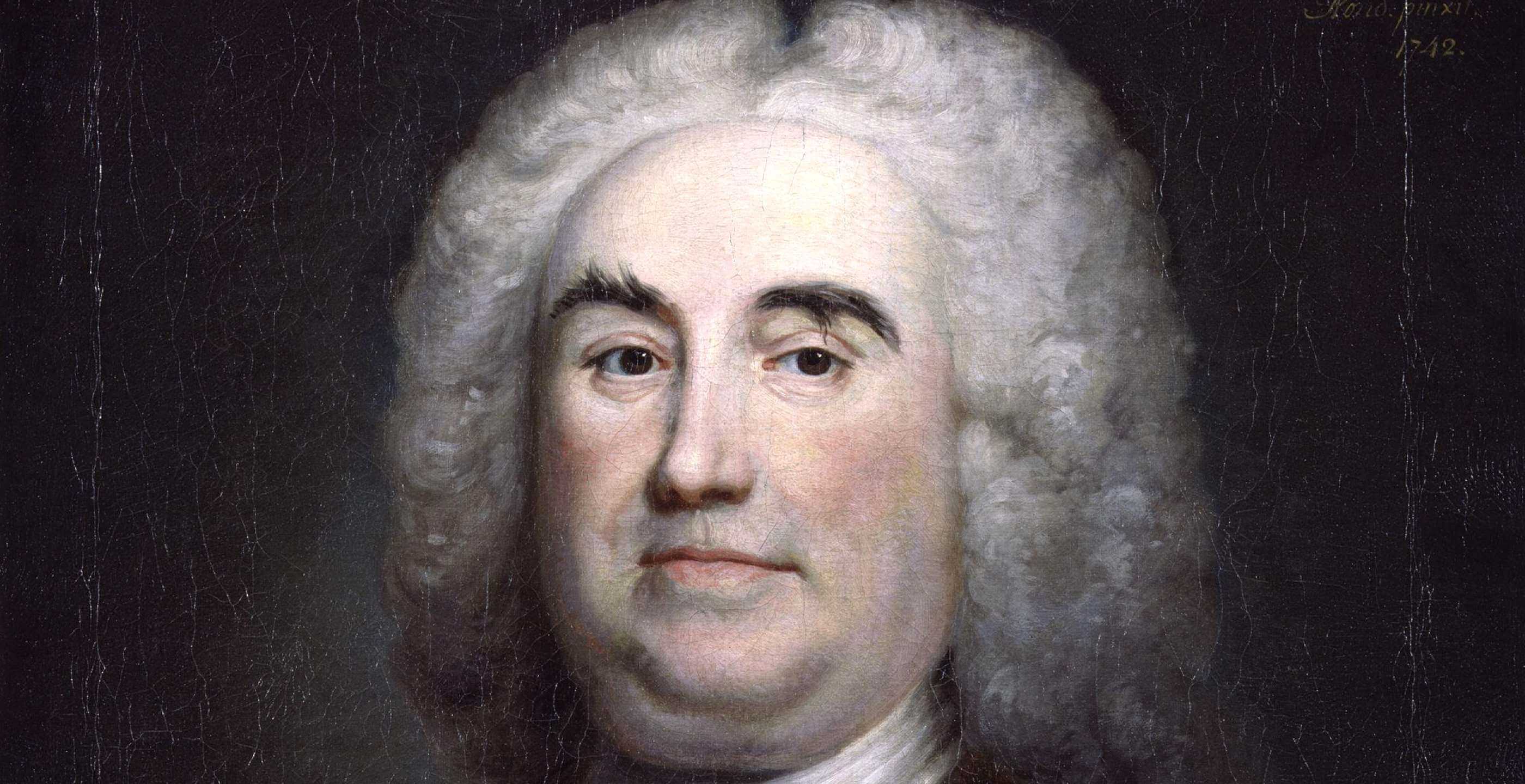

In October 1727, a second Hanoverian king was crowned at Westminster Abbey, George II, succeeding his father and continuing the battle of establishing this new dynastic royal family in British society.

George II’s life, like that of his father, began in the German city of Hanover, where he was born in October 1683, the son of George, Prince of Brunswick-Lüneburg (later King George I) and his wife, Sophia Dorothea of Celle. Sadly for young George, his parents had an unhappy marriage, leading to claims of adultery on both sides and in 1694, the damage proved irrevocable and the marriage was terminated.

His father, George I did not however simply divorce Sophia, instead he confined her to Ahlden House where she lived for the rest of her life, isolated and unable to see her children ever again.

Whilst his parents acrimonious parting led to the imprisonment of his mother, young George received a well-rounded education, learning French first, followed by German, English and Italian. He would in time become well-versed in the subject of all things military as well as learning the ins and outs of diplomacy, preparing him for his role in the monarchy.

He also went on to find a happy match in love, much unlike his father, when he was betrothed to Caroline of Ansbach whom he married in Hanover.

Having received an education in military affairs, George was more than willing to participate in the war against France, however his father was reticent in allowing his participation until he produced his own heir.

In 1707, his father’s wishes were met when Caroline gave birth to a baby boy named Frederick. Following the birth of his son, in 1708 George participated in the Battle of Oudenarde. Still in his twenties, he served under the Duke of Marlborough, on whom he left a lasting impression. His valour would be duly noted and his interest in war would be replicated once more when he assumed his role as King George II in Britain and participated at the Battle in Dettingen at the age of sixty.

Meanwhile back in Hanover, George and Caroline had three more children, all of whom were girls.

By 1714 back in Britain, Queen Anne’s health took a turn for the worst and through the Act of Settlement in 1701 which called for a Protestant lineage in the royal family, George’s father was to be next in line. Upon the death of his mother and second cousin, Queen Anne, he became King George I.

With his father now king, young George sailed to England in September 1714, arriving in a formal procession. He was granted the title Prince of Wales.

London was a complete culture shock, with Hanover much smaller and much less populated than England. George immediately became popular and with his ability to speak English, rivalled his father, George I.

In July 1716, King George I briefly returned to his beloved Hanover, leaving George with limited powers to govern in his absence. In this time, his popularity surged as he travelled around the country and allowed the general public to see him. Even a threat against his life by a lone assailant at the theatre in Drury Lane led to his profile being raised even further. Such events divided father and son further, leading to antagonism and resentment.

Such animosity continued to grow as father and son came to represent opposing factions within the royal court. George’s royal residence at Leicester House became a bedrock for opposition to the king.

Meanwhile, as the political picture began to change, the rise of Sir Robert Walpole changed the state of play for both parliament and the monarchy. In 1720, Walpole, who had previously been allied with George, Prince of Wales, called for a reconciliation between father and son. Such an act was merely done for public approval as behind closed doors, George was still not able to become regent when his father was away and neither were his three daughters released from his father’s care. In this time, George and his wife chose to remain in the background, waiting for his chance to take the throne.

In June 1727, his father King George I died in Hanover, and George succeeded him as king. His first step as king was his refusal to attend his father’s funeral in Germany which actually won high praise back in England as it showed his loyalty to Britain.

George II’s reign began, surprisingly, much like a continuation of that of his father, especially politically. At this time, Walpole was the dominant figure in British politics and led the way in policy-making. For the first twelve years of George’s reign, Prime Minister Walpole helped to keep England stable and secure from threats of international warfare, however this was not to last.

By the end of George’s reign, a very different international picture had unfolded leading to global expansion and involvement in almost continuous warfare.

After 1739, Britain found itself embroiled in various conflicts with its European neighbours. George II, with his military background was keen to engage in war, which stood in direct contrast to Walpole’s position.

With politicians exercising more restraint in the matter, an Anglo-Spanish truce was agreed, however it did not last and soon conflict with Spain escalated. The unusually named War of Jenkins’ Ear took place in New Granada and involved a stand-off in trading ambitions and opportunities between the English and Spanish in the Caribbean.

By 1742 however, the conflict had become incorporated into a much larger war known as the War of the Austrian Succession, embroiling almost all of the European powers.

Emerging from the death of the Holy Roman Emperor Charles VI in 1740, the conflict essentially broke out over the right of Maria Theresa, Charles’s daughter, to succeed him.

George was keen to involve himself in the proceedings and whilst spending the summer in Hanover, became involved in the ongoing diplomatic disputes. He involved Britain and Hanover by launching support for Maria Theresa against the challenges from Prussia and Bavaria.

The conflict reached its conclusion with the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle in 1748, which largely led to discontent from all those involved and eventually would precipitate further violence. In the meantime, the terms of the agreement for Britain would include an exchange of Louisbourg in Nova Scotia for Madras in India.

Furthermore, after exchanging territory, France and Britain’s competing interests in acquiring overseas possessions would require a commission in order to resolve the claims in North America.

Whilst war dominated the European continent, back at home George II’s poor relationship with his son Frederick began to manifest itself in much the same manner as he and his father’s not too long ago.

Frederick was made Prince of Wales when he was twenty years of age, however the rift between him and his parents continued to grow. The next step in this divisive chasm between father and son, was the formation of a rival court which allowed Frederick to focus on politically opposing his father. In 1741 he actively campaigned in the British general election: Walpole failed to buy off the prince, leading the once politically stable Walpole to lose the support he needed.

Whilst Prince Frederick had succeeded in opposing Walpole, the opposition which had garnered the support of the prince known as the “Patriot Boys” quickly switched their allegiance to the king after Walpole was ousted.

Walpole retired in 1742 after an illustrious twenty year political career. Spencer Compton, Lord Wilmington took over but only lasted a year before Henry Pelham took over as the head of government.

With Walpole’s era coming to an end, George II’s approach would prove more aggressive, particularly in dealing with Britain’s biggest rival, the French.

Meanwhile, closer to home the Jacobites, those who supported the Stuart succession claims, were about to have their swan song when in 1745, the “Young Pretender”, Charles Edward Stuart, also known as “Bonnie Prince Charlie” made one final bid to depose George and the Hanoverians. Sadly for him and his Catholic supporters, their attempts to overthrow ended in failure.

The Jacobites had made persistent efforts to reinstate the usurped Catholic Stuart line, however this final attempt marked the end of their hopes and dashed their dreams once and for all. George II as well as parliament had been suitably strengthened in their positions, now was the time to aim for bigger and better things.

In order to engage as a global player, Britain immediately drew itself into conflict with France. The invasion of Minorca, which was being held by the British, would lead to the outbreak of the Seven Years War. Whilst there were disappointments on the British side, by 1763 harsh blows to French supremacy had forced them to cede control in North America as well as lose important trading posts in Asia.

As Britain ascended the ranks in the international sphere of power, George’s health declined and in October 1760 he died at the age of seventy-six. Prince Frederick had predeceased him nine years earlier and so the throne passed to his grandson.

George II had reigned during a turbulent time of transition for the nation. His reign saw Britain take a path of international expansion and outward looking ambition, whilst finally putting to rest the challenges to the throne and parliamentary stability. Britain was becoming a world power and it looked as if the Hanoverian monarchy was here to stay.

Jessica Brain is a freelance writer specialising in history. Based in Kent and a lover of all things historical.

Published: April 27, 2021.