Suppose that before you were born, you were given a preview of what your life would be like; then given a choice – Mission Impossible style – of whether you wished to accept it.

Then suppose that this is what you were told:

“You will achieve immortality. Your name will echo down the generations as great a British hero. That’s the good news. The bad news is that you will die young, violently, far from home, after a life tainted by disappointment, rejection and heartache.”

What would you decide?

One problem with historical figures is that we tend to take a one-dimensional view of them. We define them solely by their moments of triumph, or honour. We fail to look at the person within, the emotional vicissitudes they might have endured and to consider what effect those experiences may have had on them.

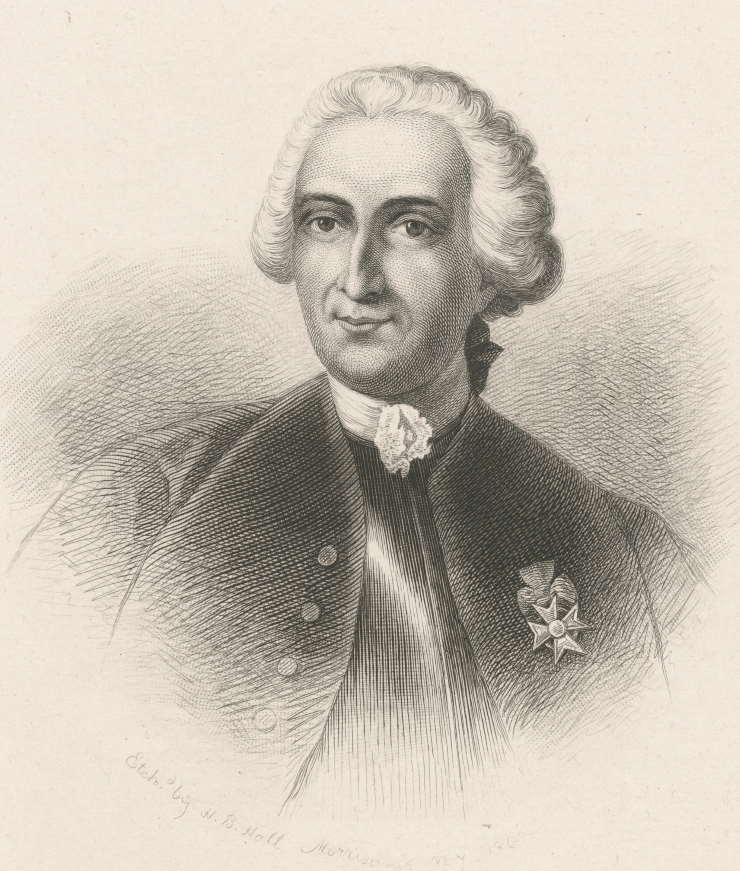

The case of James Wolfe, born at Westerham, Kent on 2nd January 1727 illustrates this failing as well as any.

Born into an upper-middle class military family, there was little doubt about the career path the young James would follow. Commissioned as an officer at 14 and thrown straight into military conflicts in Europe, he rose quickly through the ranks thanks to his strong sense of duty, energy and personal bravery. By the age of 31 he had rocketed to Brigadier-General and was second in command of Prime Minister Pitt’s massive military operation to seize French possessions in North America (what is now Canada).

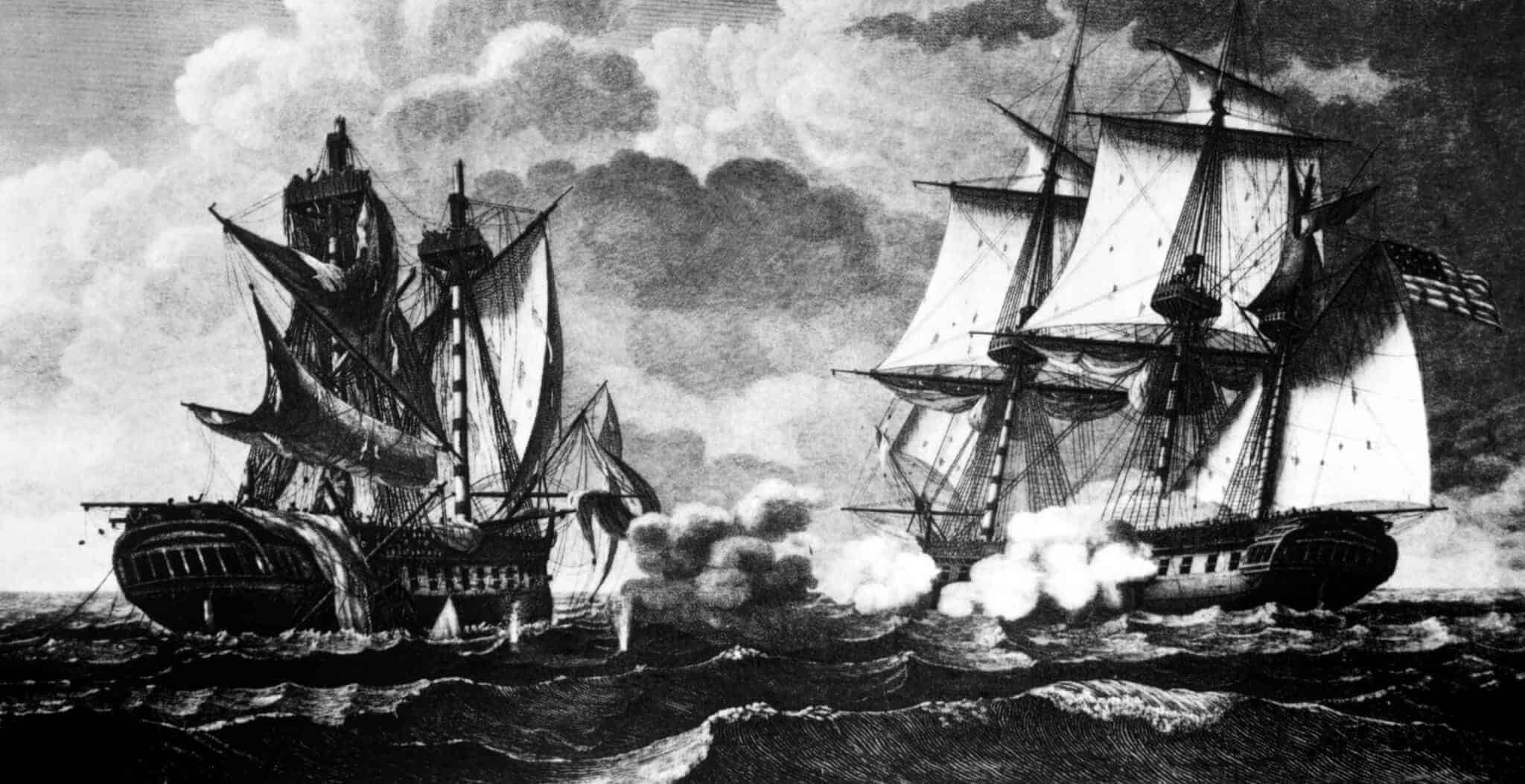

After an inspirational role in the amphibious assault on the French coastal stronghold of Louisburg, Pitt then gave Wolfe full command of the headline operation to lay siege to and capture the French capital of Quebec.

But as his military star soared in the sky, Wolfe’s personal life was mired in struggle and setbacks.

The greatest handicap to his personal happiness was, sadly, his unusual appearance. He was exceptionally tall, skinny and had a sloping forehead and weak chin. From the side, in particular, he was said to look very odd. A Quebec woman, captured as a spy and interrogated by Wolfe, later said that he had behaved to her as a perfect gentleman but described him as a “very ugly man.”

Such an affliction did not help in his desire to seek a wife but, when he was twenty-two, he courted an eligible young woman, Elizabeth Lawson, who was said in some ways to be of similar appearance to him and with a “sweet temperament.” Wolfe was smitten and sought the consent of their parents to marry, but in a crushing blow Wolfe’s mother (to whom he was very close) rejected the match, seemingly on the grounds that Miss Lawson didn’t command a large enough dowry. The damage caused to the relationship between the dutiful son and his parents was hurtful but, when his mother rejected a second possible marriage partner, Katharine Lowther, shortly before Wolfe sailed to America, he broke off all relations with his parents and never spoke to or saw them again.

The family breakdown was compounded by the early death of his brother Edward from consumption, an event which threw Wolfe into deep grief and self-reproach for being absent from his brother’s side at the last.

Wolfe had also suffered from ill-health intermittently, especially abdominal problems, and the compound effect of this, added to the upsetting circumstances, meant that by the time he led his troops upon Quebec, he was certainly “not in a good place.” He even began to doubt whether the responsibility thrust upon him was more than he could handle. He had been left in no doubt that this campaign was not a mere regional struggle but a strategy by Pitt to destroy France as a European powerhouse. There was an awful lot riding on it.

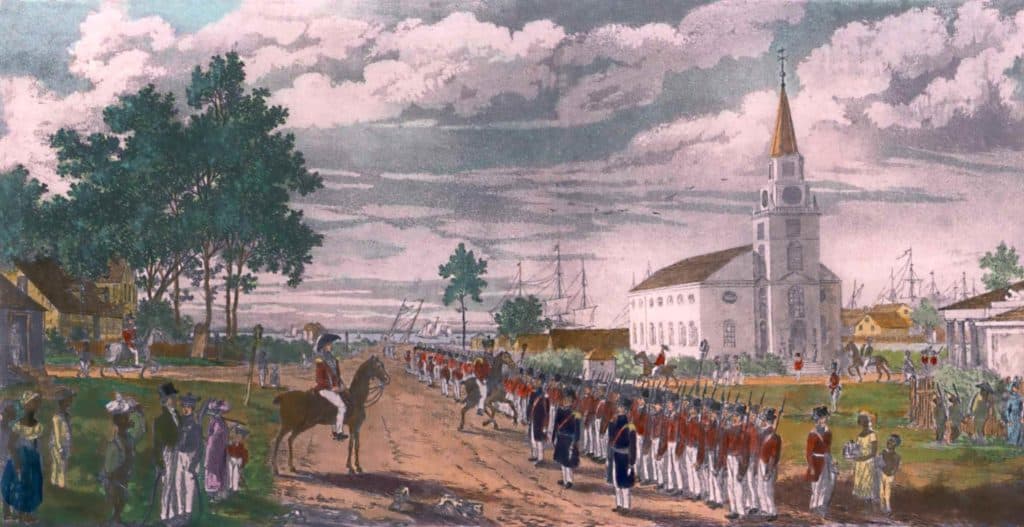

When he led his men up the St Lawrence river and caught his first glimpse of the walled city of Quebec, it can hardly have cheered him. The French had built their capital on a high rocky outcrop (a kind of mini-Gibraltar) that jutted out into the centre of the wide and fast-flowing St Lawrence. Flanked to the north and south by water, the landward approach from the East was defended by a powerful French army supported by local militia and commanded by the veteran Marquis de Montcalm. In theory, if the British could get beyond the city, they could attack up a gradual slope known as the Heights of Abraham. But to get their ships upriver would mean sailing under the French canon on the ramparts, and the surrounding forests were teeming with Indian warriors allied to the French.

For almost three months Wolfe struggled with this impossible dilemma. He brought up siege artillery to bombard the city and attempted a full-scale assault against the French army which ended disastrously. As the weeks turned into months, his health and confidence began to decline, while opposition to him began to flare up. He had always been popular among the rank and file, but hostility among jealous subordinate officers spread. A sense of paralysis seemed to have set in.

Finally, in mid-September and with the approach of the severe Canadian winter, Wolfe bowed to pressure and agreed to gamble all on an attack upriver over the Heights of Abraham. The French artillery had been seriously weakened by the siege and in dead of night he sailed his army upstream beyond Quebec to where in an earlier reconnaissance, he had spotted a concealed gully up from the riverbank on to the Heights. At a moment of great emotional stress in his life he is said to have read from ‘An Elegy written In a Country Churchyard’ by Thomas Gary to his officers and said “I would rather have written that poem than take Quebec.”

But Wolfe’s greatest strength was leading his men in battle and, with complete disregard for his own safety, he was among the first to ascend the Heights and to march upon the city. As Montcalm brought up his army and shots rang out Wolfe, right in the vanguard, was shot in the wrist, then the stomach before, still urging his men forwards, a third shot through the lung brought him down. As he slowly drowned in his own blood, he held on long enough to be told the French were retreating and his last words expressed his great relief that he had done his duty.

Wolfe’s victory at Quebec would ensure the defeat of France and Britain’s conquest of all America and lay the foundation for modern Canada. For him personally, like Nelson at Trafalgar, he would acquire legendary status and be lionised as a wise, venerable commander. For his bravery and duty that was deserved. But in reflecting also on all the things in his life that caused him unhappiness, grief, sorrow and self-doubt, we do more justice to his true nature and understand how this one person coped with the complexity and contradictory nature of human life.

Author’s Note: Wolfe’s childhood home, Quebec House, at Westerham, Kent, is owned by the National Trust and open to visitors during the summer months.

Richard Eggington has nearly 30 years’ experience of lecturing and writing on American Colonial and Western history.

Published: 27th January 2017.