“When can their glory fade?

O the wild charge they made!”

These words were made famous by Alfred Lord Tennyson in his poem, ‘The Charge of the Light Brigade’, and refer to that fateful day on 25th October 1854 when around six hundred men led by Lord Cardigan rode into the unknown.

The charge against Russian forces was part of the Battle of Balaclava, a conflict making up a much larger series of events known as the Crimean War. The order for the cavalry charge proved catastrophic for the British cavalrymen: a disastrous mistake riddled with misinformation and miscommunication. The calamitous charge was to be remembered for both its bravery and tragedy.

The Crimean War was a conflict which broke out in October 1853 between the Russians on one side and an alliance of British, French, Ottoman and Sardinian troops on the other. During the following year the Battle of Balaklava took place, beginning in September when Allied troops arrived in Crimea. The focal point of this confrontation was the important strategic naval base of Sevastopol.

The Allied forces decided to lay siege to the port of Sevastapol. On 25th October 1854 the Russian army led by Prince Menshikov launched an assault on the British base at Balaklava. Initially it looked as if a Russian victory was imminent as they gained control of some of the ridges surrounding the port, therefore controlling the Allied guns. Nevertheless, the Allies managed to group together and held on to Balaklava.

Once the Russian forces had been held off, the Allies decided recover their guns. This decision led to one of the most crucial parts of the battle, now known as the Charge of the Light Brigade. The decision taken by Lord Fitzroy Somerset Raglan who was the British commander-in-chief at Crimea, was to look towards the Causeway Heights, where it was believed the Russians were seizing artillery guns.

The command given to the cavalry, made up of Heavy and Light Brigades, was to advance with the infantry. Lord Raglan had conveyed this message with the expectation of immediate action by the cavalry, with the idea that the infantry would follow. Unfortunately, due to lack of communication or some misunderstanding between Raglan and the commander of the Cavalry, George Bingham, Earl of Lucan, this was not carried out. Instead Bingham and his men held off for around forty five minutes, expecting the infantry to arrive later so they could proceed together.

Unfortunately with the breakdown in communication, Raglan frantically issued another command, this time to “advance rapidly to the front”. However, as far as Earl of Lucan and his men could see, there were no signs of any guns being seized by the Russians. This led to a moment of confusion, causing Bingham to ask Raglan’s aide-de-camp just where the cavalry were supposed to attack. The response from Captain Nolan was to gesticulate towards the North Valley instead of the Causeway which was the intended position for attack. After a little deliberation back and forth, it was decided that they must proceed in the aforementioned direction. A terrible blunder that would cost many lives, including that of Nolan himself.

Those in a position to take responsibility for the decisions included Bingham, the Earl of Lucan as well as his brother-in-law James Brudenell, the Earl of Cardigan who commanded the Light Brigade. Unfortunately for those serving under them, they loathed each other and were barely on speaking terms, a major issue considering the severity of the situation. It had also been said that neither character had earned much respect from their men, who were unfortunately obliged to obey their ill-fated commands on that day.

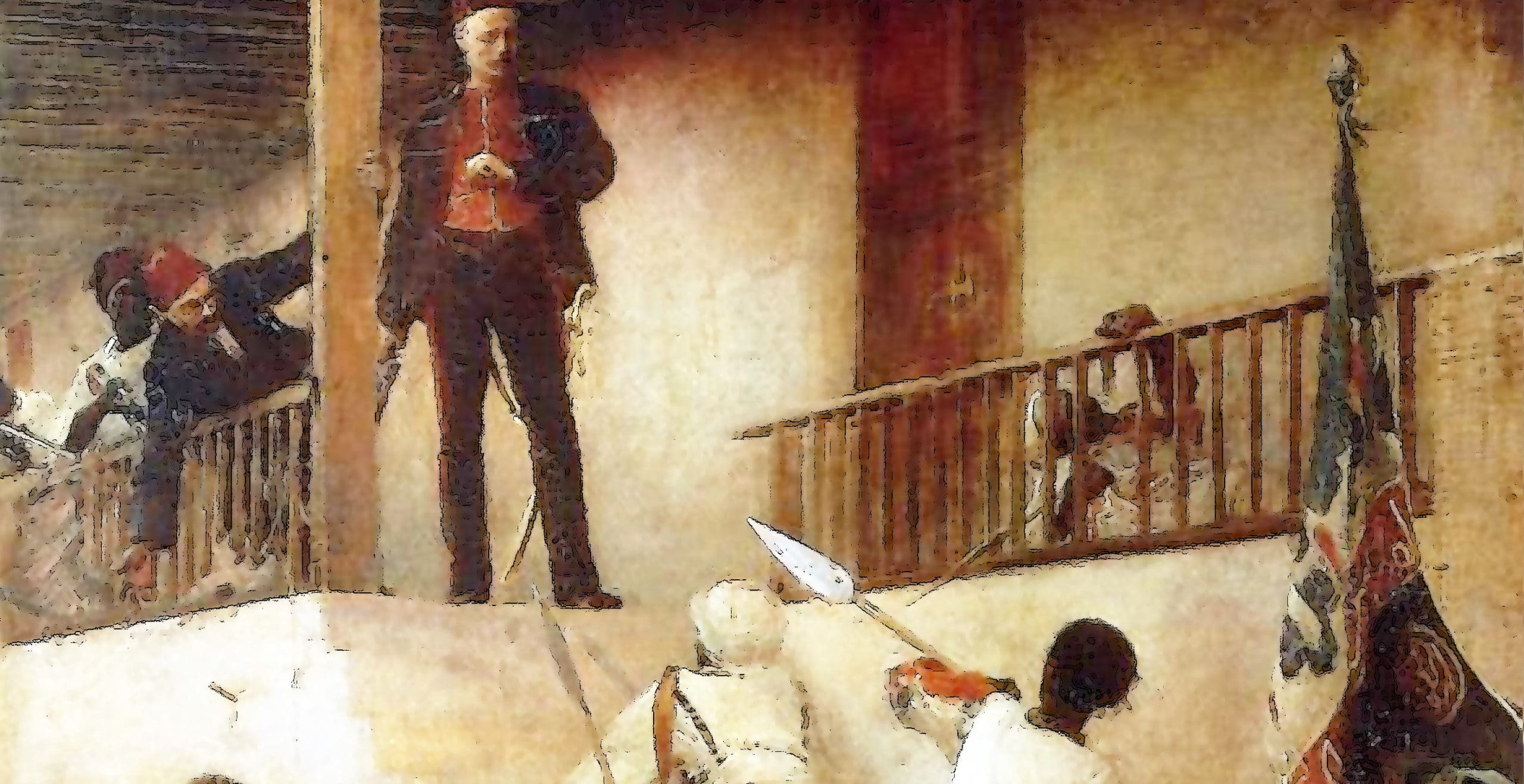

Lucan and Cardigan both decided to proceed with the ill-interpreted orders despite expressing some concern, therefore committing around six hundred and seventy members of the Light Brigade into battle. They drew their sabres and began the doomed mile-and-a-quarter-long charge, facing Russian troops who were firing on them from three different directions. The first to fall was Captain Nolan, Raglan’s aide-de-camp.

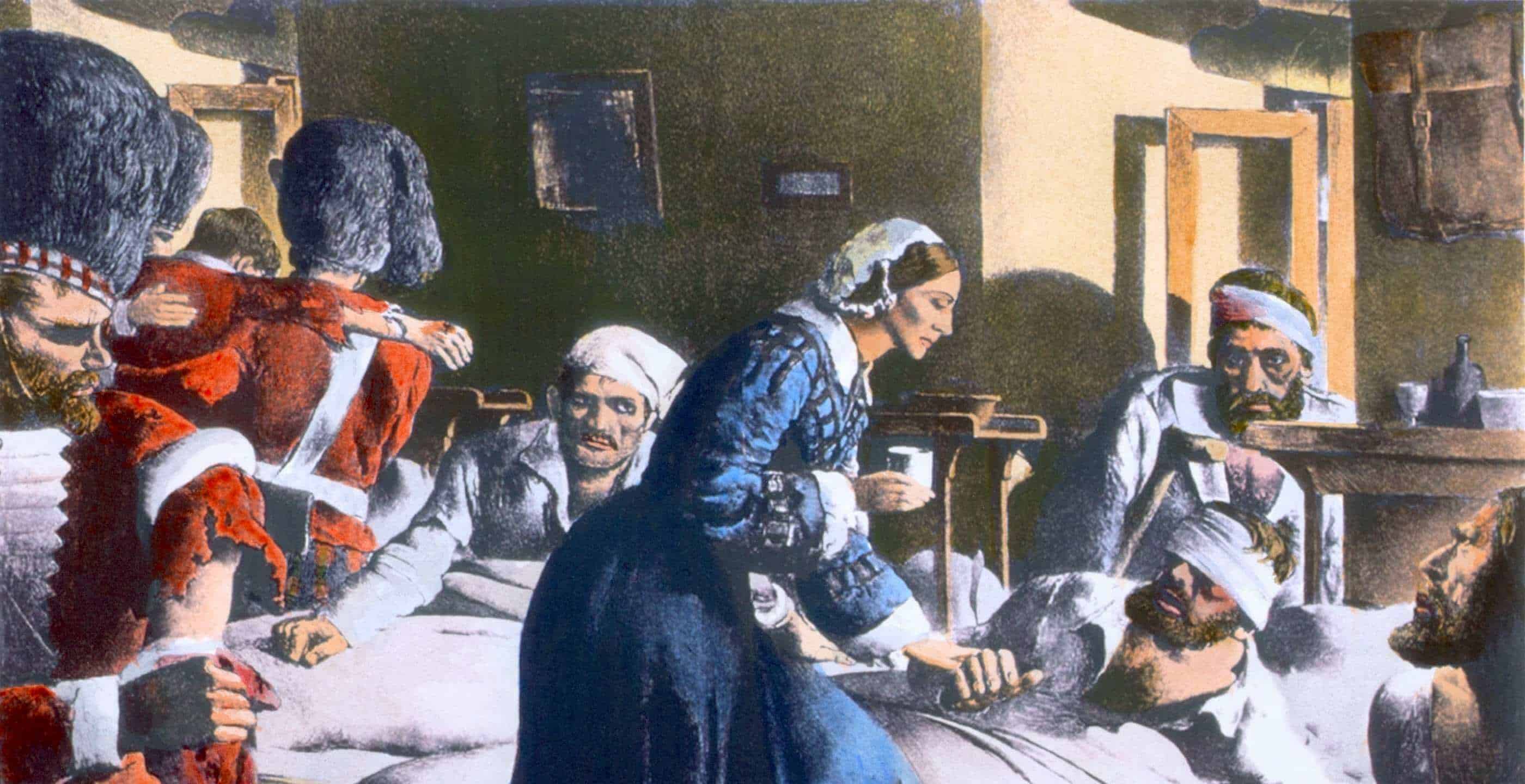

The horrors that followed would have shocked even the most experienced officer. Witnesses told of blood splattered bodies, missing limbs, brains blown to smithereens and smoke filling the air like a huge volcanic eruption. Those who did not die in the clash formed the long casualty list, with around one hundred and sixty treated for wounds and about one hundred and ten dead in the charge. The casualty rate amounted to a staggering forty percent. It was not just men who lost their lives that day, it was said that the troops lost approximately four hundred horses that day too. The price to pay for lack of military communication was steep.

Whilst the Light Brigade charged helplessly into the aim of Russian fire, Lucan led the Heavy Brigade forward with the French cavalry taking up the left of the position. Major Abdelal was able to lead an attack up to the Fedioukine Heights towards the flank of a Russian battery, forcing them to withdraw.

Slightly wounded and sensing that the Light Brigade were doomed, Lucan gave the order for the Heavy Brigade to halt and retreat, leaving Cardigan and his men without support. The decision taken by Lucan was said to be based on the desire to preserve his cavalry division, the ominous prospects of the Light Brigade being already unsalvageable as far as he could see. “Why add more casualties to the list?” Lucan is reported to have said to Lord Paulet.

Meanwhile as the Light Brigade charged into an endless smog of doom, those who did survive engaged in battle with the Russians, attempting to seize the guns as they did so. They regrouped into smaller numbers and prepared to charge the Russian cavalry. It is said that the Russians attempted to deal with any survivors swiftly but the Cossacks and other troops were unnerved to see the British horsemen charging towards them and panicked. The Russian cavalry pulled back.

By this point in the battle, all of the surviving members of the Light Brigade were behind the Russian guns, however lacking the support of Lucan and his men meant that the Russian officers quickly became aware that they outnumbered them. The retreat was therefore halted and an order was given to charge down into the valley behind the British and block their escape route. For those watching on, this looked to be a chillingly dire moment for the remaining Brigade fighters, however miraculously two groups of survivors quickly broke through the trap and made a break for it.

The battle was not over yet for these daring and courageous men, they were still coming under fire from guns on the Causeway Heights. The astounding bravery of the men was even acknowledged by the enemy who were said to have remarked that even when wounded and dismounted, the English would not surrender.

The mixture of emotions for both the survivors and onlookers meant that the Allies were incapable of continuing with any further action. The days, months and years that followed would lead to heated debates in order to apportion blame for such unnecessary misery that day. The Charge of the Light Brigade will be remembered as a battle steeped in bloodshed, mistakes, regret and trauma as well as valour, defiance and endurance.

Jessica Brain is a freelance writer specialising in history. Based in Kent and a lover of all things historical.

Published: 3rd July 2019.