IN July 1901 a heatwave welcomed both the end of six months of official mourning for the death of Queen Victoria and the launch of the Edwardian era. Temperatures rocketed beyond 90 degrees Fahrenheit, causing deaths and a harvest crisis.

This coincided with a dramatic cultural phenomenon. It was, said one commentator, as though ‘the dam of Victorian rectitude had burst wide open’. Suddenly, it seemed, Britain was determined to enjoy itself – particularly at the weekend. Sunday church attendances plummeted and Archdeacon Madden of Liverpool complained: “Young men are turning the Sabbath into pleasure seeking…the roads are almost impassable with bicycle riders off for the day.”

Cycling was a major recreation. Hundreds of thousands of wheelers poured out from the suburbs and into the sun-burned English countryside. They took pre-determined routes advertised in local papers, stopping at roadside cafes for tea, ice-cream and lemonade – one brand touted that it was ‘partly made in Italy’, although it had a distinctive French title, ‘Eiffel Tower Lemonade’.

Many magazines carried adverts for a product known as ‘The Cyclist’s Friend’, or, sometimes, ‘The Traveller’s Friend’. A puncture outfit, perhaps? A waterproof cape? Not so. The ‘friend’ was a potential killer, a scaled-down handgun which could be easily stowed into a pocket or a handbag. Maybe a Colt .32, a tiny version of the .45 which ‘tamed the Wild West’ of America. Or a revolver produced by the Staffordshire firm of T W Carryer and Co Ltd which they named specifically as ‘The Cyclist’s Friend’, costing 12 shillings and sixpence, and marketed with the tag: ‘Fear no tramp.’

An illustration of a ‘Cyclist’s Friend’, a small, short-barrelled revolver

An illustration of a ‘Cyclist’s Friend’, a small, short-barrelled revolver

The sales of these weapons leaned heavily on reports of lone cyclists, usually women, being attacked by robbers and vagrants as they pedalled along England’s rural roads.

‘No lady or gentleman should be without one’ sang the Carryer advert. One American company boasted that their ‘Cyclist’s Revolver’ could not be fired accidentally. And just to show how safe it was, they portrayed a young girl playing with one as she sat on a bed, her doll pushed to one side.

Britain had no effective legislation to restrict the ownership or use of handguns. You could be insane, a hardened criminal or just a member of a shooting club and whether at a gunsmith’s, a local hardware store, in a pub or by mail order, you could buy a revolver or a pistol with cartridges, no questions asked. Colts, one of the major manufacturers, claimed that British sales of their Pocket Revolver, the Colt .32, had risen into the ‘thousands’ between its introduction in 1893 and the summer of 1901. Yet gun crime was comparatively rare and demands for stricter control were usually brushed off.

However, the issue simmered in the late 19th century partly because of anxiety over increased terrorist activity, and it boiled over in that blistering summer of 1901 when a senior judge dealt with two murder cases.

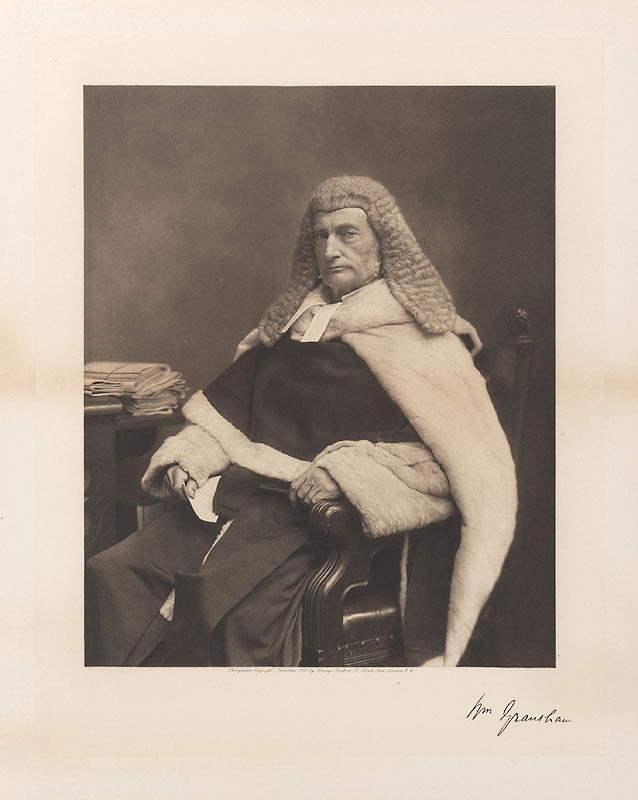

Sir William Grantham was an outspoken Assize Court judge. A former MP, he locked horns with the Dean of Durham who had condemned the drunken behaviour of Volunteer soldiers as they prepared to fight in the Anglo-Boer conflict. And, later, he was publicly rebuked in the House of Commons for using a courtroom to air indiscreet political opinions. But when, during the murder hearings, the judge ripped into gun merchants, his words carried weight.

The first trial was of a 26-years-old man with serious psychiatric problems who had purchased a German made revolver and ammunition for 10 shillings in a Leeds shop and, a short while later, had shot dead his friend as they walked along the street. Judge Grantham hauled the shop owner into the witness box and told him: “It is because of people like you that these murders take place.”

In the middle of the heatwave, Sir William presided over a case at Chester where a 21-years-old labourer was accused of blasting a tailor to death with five shots from a Colt .32 for no apparent reason. The accused had purchased the revolver, in a leather case, and 100 cartridges by mail order for £4 14s. During the hearing, the judge interrogated a representative of Colts about the gun and was told: “We advertise it as suitable for travellers and cyclists.”

Grantham said: “Surely, you don’t mean to suggest that cyclists run such risks that they feel the need to carry revolvers?”

Came the reply: “It is for self-protection, generally from dogs which can get caught up between the wheels and upset the cyclist.”

Grantham, obviously unimpressed, retorted: “So cyclists are to murder dogs?”

In December 1901, while dealing with another shooting, the judge issued a general warning to all cyclists tempted to carry a ‘friend’ on their travels. “If he kills anyone he will be hanged and if he wounds anyone he will be sent to Penal Servitude (a long sentence with hard labour). All cyclists had better bear that in mind.”

Sales of these weapons decreased and less than two years after the judge’s intervention came the first worthwhile attempt at gun control in the UK, The Pistols Act of 1903. This proved ineffective. After World War One firmer action was needed. Britain was flooded with military service revolvers and, after having to deal with race riots, police strikes and other unrest, the government introduced stronger legislation with The Firearms Act of 1920.

Colin Evans is a retired journalist