Whilst today the term Black Friday might evoke images of sales and panicked shoppers with an eye for a bargain, in 1910 it meant something very different indeed.

On 18th November 1910 in central London, 300 protesting suffragettes were subjected to a brutal suppression of their demonstration, experiencing physical assault by police and bystanders alike.

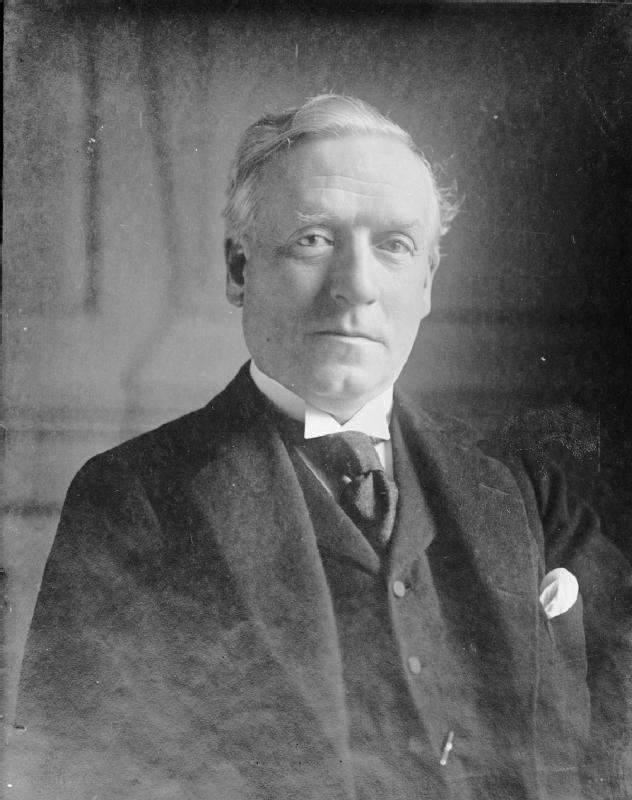

The origin of this clash dated back to the beginning of the year when the 1910 general election was held with Prime Minister Asquith, also Liberal Party Leader, making promises which he sadly would not keep.

This included, that if re-elected, he would introduce the Conciliation Bill which proposed the extension of the rights of women to vote resulting in around one million eligible women becoming enfranchised. The minimum qualification for this right was for women who owned property and had a certain degree of wealth. Whilst restrictive by today’s standards, it would form a vital stepping stone in a much larger quest for universal suffrage.

Whilst faith in Asquith’s promises was still tentative from the suffragette camp, Emmeline Pankhurst made the announcement that the group known as WSPU would be focusing on constitutional campaigning rather than its characteristic militancy.

With Asquith laying out his mandate, the election resulted in a hung parliament with the Liberals just able to cling on to power but with their majority lost.

With a newly formed government, it was time to proceed with the promises he had made during his election campaign, including the Conciliation Bill.

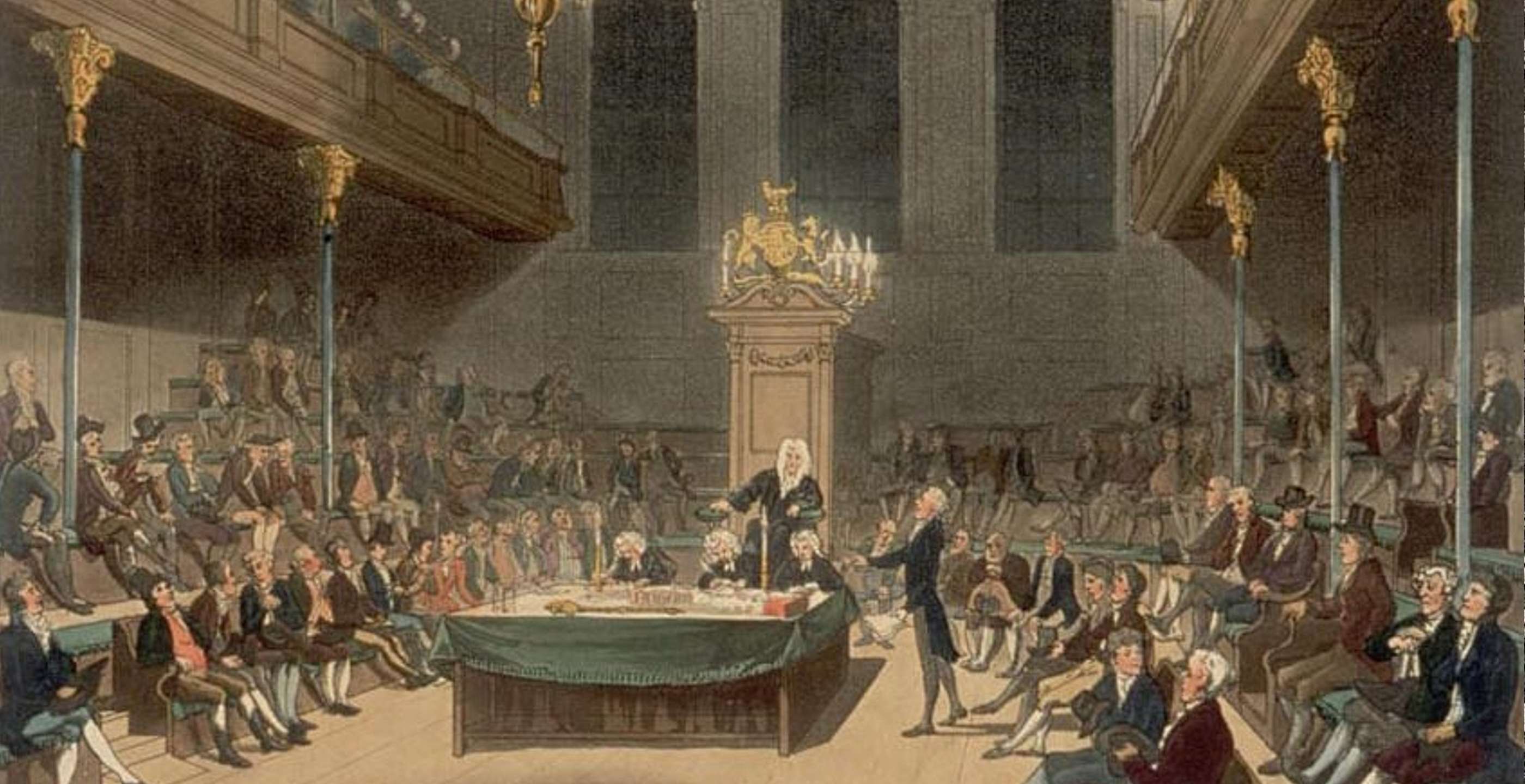

The appetite for this type of legislation had been growing as the bill itself had been put together by a committee comprising pro-suffrage Members of Parliament from across the House of Commons under the leadership of Lord Lytton.

With enough backing from MPs, the bill was able to make it through the usual parliamentary procedure, passing its first and second readings.

Despite the initial success of the legislature, the divisiveness of the issue led to the bill being discussed on three occasions. During a cabinet meeting in June, Asquith made it clear that he would not allocate any further parliamentary time and therefore the bill was doomed to fail.

Such an outcome unsurprisingly was met with uproar by those who had supported the move, including nearly 200 Members of Parliament who subsequently signed a memorandum that asked the Prime Minister for more time to debate. The request was turned down by Asquith.

With parliament now scheduled to reconvene in November, Pankhurst and the other suffragettes held back on their response until the outcome was made clear and they could plot their next move.

By 12th November, the Liberal Party made it clear that any hopes of Asquith awarding more time for the bill had been dashed. The government had spoken and the conciliation legislation had been put to bed.

Upon hearing the news, the WSPU resumed their tactics and began making arrangements for a protest to be held outside Parliament.

On 18th November, the government was in disarray and Asquith in response called for another general election to be held whilst parliament would be dissolved for the next ten days.

With no mention of the Conciliation Bill, the WSPU went ahead with their plans to protest.

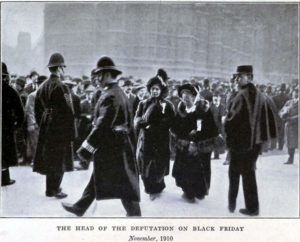

With the campaigners set to descend on Westminster, the WSPU led by its most famous figure, Emmeline Pankhurst, led around 300 of its members in a rally to parliament. Amongst the protesters were prominent campaigners such as Dr Elizabeth Garrett Anderson and her daughter Louisa as well as Princess Sophia Alexandrovna Duleep Singh.

The women were organised into smaller separate groups as they launched their protest, with the first delegation arriving and asking to be taken to Asquith’s office. Sadly, their request was met with a refusal as the Prime Minister denied their attempts to meet.

With the suffragettes’ demonstration known to the authorities, the usual police unit known as the A Division who had previously been deployed to deal with them was not used, and instead police were drafted from other locations in London. This made the situation more fraught as the A Division had become accustomed to suffragette protesters and knew how to deal with them with a level of “courtesy and consideration”, as described by Sylvia Pankhurst. Sadly, the events of the day were destined to play out very differently.

In the chaos that ensued over the next six hours, differing accounts from a range of bystanders, participants and the press made it difficult to ascertain the exact conduct of all involved, however the abuse, sexual, physical and verbal, was something which marked out this day forever as a dark day in the history of public protest.

As the convening groups of women approached their meeting point at Parliament Square, bystanders began to subject the women to verbal and sexual abuse, which included groping and manhandling the protesters.

Further along, as the line of policeman was approached, the violence continued as the women were met with a slew of insults and violent tactics from the police on duty that day. Rather than taking the women off to be arrested, abusive rhetoric back and forth began to dominate proceedings.

For the next six hours the women faced a barrage of abuse, both verbal and physical, as they attempted to enter parliament. Whilst the police managed to deter the women from breaking in by throwing them back into the crowds, often the women would be subjected to further assaults.

Some of the most common injuries incurred included black eyes, bruised bodies, nose bleeds as well as some sprains and more serious injuries that required treatment at a medical post set up at Caxton Hall.

One prominent suffragette called Rosa May Billinghurst, a well-known disabled campaigner, had also been the victim of assault by the police.

The accounts of sexual violence and police brutality were rife with the police eventually arresting 115 women and four men although charges against them would later be dropped.

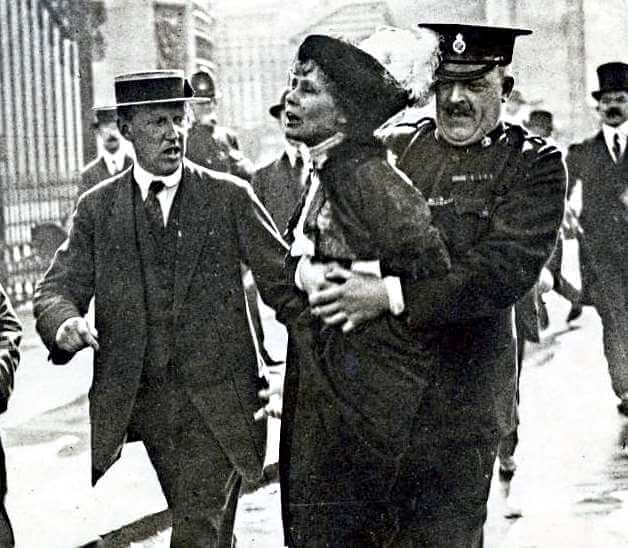

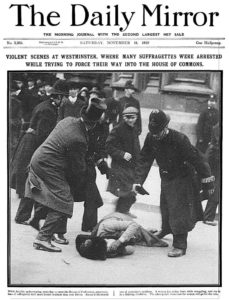

Perhaps one of the most enduring moments of the brutality from that day was captured in photograph and subsequently printed the next day.

The image depicts the moment that campaigner Ada Wright is laying on the ground, already the victim of numerous hits and shoves by police. Surrounded by men, one gentleman attempts to protect her as she lays prostrate, however he is subsequently shoved to the ground himself and Ada becomes the subject of more violence as she is picked up and tossed back into the crowds.

Such an experience was replicated and inflicted on many women during the protest, leaving many unanswered questions the following morning.

With just over 100 women rounded up and arrested by the police, the following day all charges were dropped on the advice of Winston Churchill who believed that there was no prospect of a good outcome if they proceeded with convictions.

Meanwhile the national press coverage, including the iconic image of Ada Wright on the front of the Daily Mirror, discussed the previous day’s events, with many other periodicals refraining from mentioning the scale of police brutality. Instead, some of the papers extended sympathy for the injuries incurred by the police officers as well as expressing condemnation for the violent tactics employed by the suffragettes.

Upon hearing the testimonies of those involved, the committee which had formed to pass the bill immediately called for a public inquiry. After collecting statements from around 135 women who corroborated each other’s stories of brutality and abuse, Henry Brailsford, a journalist and secretary to the committee, as well as psychotherapist Jessie Murray, put together a memorandum.

Within this were explicit details of some of the most common tactics used by the police, which included twisting the nipples and breasts of the protesters which was often accompanied by a slew of lurid and sexual remarks.

In February the following year, the memorandum was compiled and presented to the Home Office alongside the public inquiry request, however it was to be subsequently rejected by Churchill.

A month later in parliament the issue was raised once more, to which Churchill responded by refuting any implication that police were given an instruction to use violence and that any claims of indecency raised by the publication of the memorandum were “found to be devoid of foundation”.

With the formal response to the events on Black Friday ending with Churchill’s refusal to launch a public inquiry, the impact on those involved continued to have its effect, especially when two suffragettes died not long afterwards leading to enormous speculation as to the contribution of Black Friday events to their demise.

For members of the WSPU, Black Friday had become a watershed moment. Some women simply rescinded their membership, too afraid to participate, whilst others adopted tactics such as window breaking which could be executed quickly and enable them to flee without prospect of contact with the police.

Likewise, those in authority were forced to dwell on their actions and analyse the effectiveness of their tactics.

The date 18th November 1910 would become indelibly marked on the suffragette campaigners as a tipping point and moment for reflection, with protesters seeking the same goals with the same conviction but with new approaches.

Black Friday was a dark day for all involved, however the fight was far from over.

Jessica Brain is a freelance writer specialising in history. Based in Kent and a lover of all things historical.

Published: 10th April 2022.