“I seemed to see a furnace of torment and death and agony and terror seven times heated, and in the midst of the burning was the British Army. In the midst of the flame, consumed by it and yet aureoled in it, scattered like ashes and yet triumphant, martyred and forever glorious. So I saw our men with a shining about them, so I took these thoughts with me to church, and, I am sorry to say, was making up a story in my head while the deacon was singing the Gospel. This was not the tale of ‘The Bowmen’; it was the first sketch, as it were, of ‘The Soldier’s Rest’…” – Arthur Machen, “The Angels of Mons: The Bowmen, and other Legends of the War”, 1915

The British Expeditionary Force experienced its first major engagement of the First World War in the intense heat of the summer of 1914. The troop numbers involved were all in favour of the advancing German forces, yet the outnumbered British army succeeded in holding them back before being forced into retreat the following day.

This brief success – at a heavy cost in casualties on the British side – might have been viewed as miraculous in itself. However, that was not the reason that the engagement known as the Battle of Mons achieved lasting fame. In a very short space of time after the battle, publications were claiming the British Army’s achievement was due to divine intervention in the form of heavenly beings who would later become identified as “The Angels of Mons”.

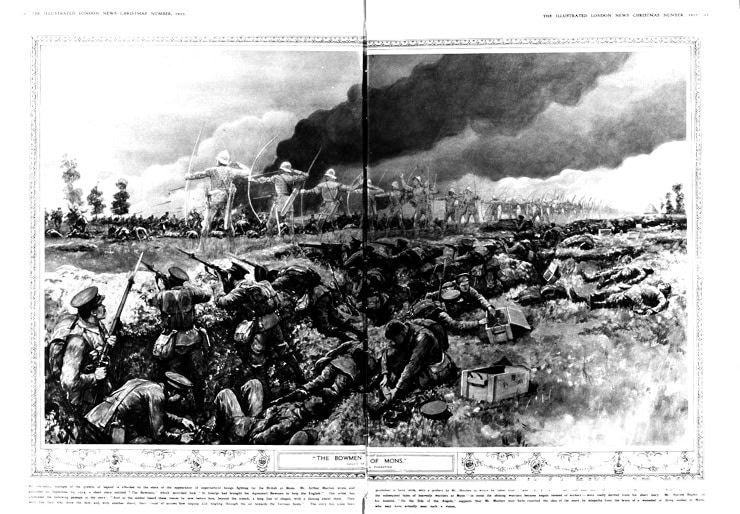

At a time when communication via telephone and telegraph meant stories could be gathered in at incredible speed by a news-hungry press, the Angels of Mons legend swiftly gained momentum. The battle had taken place on the 22nd – 23rd August 1914. By November of the following year, the Illustrated London News was publishing an article on how the “Ghostly Bowmen of Mons” had helped to defeat the Germans. The legend was firmly established by this time. In the interim, there had been many other publications about the alleged supernatural intervention, and the ghost bowmen had gradually transformed through “shining beings” or a “shining cloud” into angels.

The beginning of the legend dates to the publication on 29th September 1914 of a short story by Arthur Machen (1863-1947) titled “The Bowmen” in the Evening News. Machen was the son of a Welsh vicar, and as was not unusual for that generation, was not only steeped in Christian knowledge but also mythology and pagan lore. He was a near contemporary of the infamous Aleister Crowley, and a member of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn. In 1893 Machen had published a controversial (and sensational) horror novel “The Great God Pan”. Having read an account of the retreat from Mons in the Weekly Dispatch in 1914, he now had a vision of the British forces enduring heat and burning that inspired him to create his fictional account.

“The Bowmen” is Machen’s story of a British soldier recalling, while shooting during an unspecified battle whose circumstances suggest Mons, his visits to a vegetarian restaurant in London where “he had once or twice eaten eccentric dishes of cutlets made of lentils and nuts that pretended to be steak”. He recalls that all the plates had an image of St George on them, with the Latin motto “Adsit Anglis Sanctus Georgius” (“May Saint George be a present help to the English”). The rifleman begins to mutter the phrase as he shoots.

On experiencing a sudden electric shock in his body, he hears a great voice crying “Array, array, array!” Saint George has heeded his prayer for assistance, and arrived with “a long line of shapes, with a shining about them” who take aim and shoot arrows at the enemy. They are the spirits of archers who served at Agincourt. By the time the engagement is over, 10,000 of the enemy lie dead. The battle is an inexplicable success for the British that leaves the Germans wondering what deadly secret weapon their enemies had at their disposal.

“Having written my story,” wrote Machen in the introduction to the 1915 collection of his tales, “having groaned and growled over it and printed it, I certainly never gave thought to hear another word of it.” He received a supportive review from a colleague, who queried why English bowmen should use French terms in his story (“struck me as picturesque” replied Machen, pointing out that the original bowmen at the Battle of Agincourt were mostly Welsh anyway) and that, he thought, was that. Most significantly, the story was not identified clearly as a fictional tale on its first publication.

Of all his work, Machen never thought much of the story – in fact he admitted to being “heartily disappointed” by it – and was as astonished as anyone by its strange and influential afterlife. He also admitted it owed a debt to a story of Rudyard Kipling of ghostly soldiers, augmented by “the mediaevalism that is always there” in his mind. Within a few days the Occult Review wrote to him asking whether there was any factual foundation to the tale, as did the editor of the spiritual journal Light. Machen told them, and subsequent enquirers, there was no basis of fact for the story.

The tale proved to be far more popular than Machen had ever imagined, and soon he and the newspaper were being bombarded with requests to reprint the story. By April 1915 something even more extraordinary was happening. Parish magazines that reprinted the story were selling out and one priest approached Machen implying that there must have been some basis of fact to “The Bowmen”.

In vain did Machen say no, that it was simply the product of his own imagination: “the snowball of rumour that was then set rolling has been rolling ever since, growing bigger and bigger, until it is now swollen to a monstrous size”.

Machen began to read stories that centred on a vegetarian restaurant similar to that in his tale. (According to Roger Clarke, author of “Ghosts: a Natural History”, a restaurant with patriotic inscriptions on the plates did exist.) He read another version that described Prussian troops lying dead on the battlefield with the unmistakable evidence of arrow wounds in their bodies. Machen found this amusing, as he’d already come up with that idea and discarded it as being too unlikely to be acceptable to the readership of his original tale.

Then clouds and shining people began to emerge in some of the versions, and from there, as Machen himself noted, it was but a small step to the idea of angels. Perceptively he noted that the strength of Protestantism in Britain had meant that saintly iconography and belief had mostly been discarded, but Saint George had proved useful as an aid to patriotism. Also, that angels were more acceptable to Protestant belief than saints, and so the image of angels proved appropriate to both Protestants and a reinvigorated Catholicism at that time.

In under a year, the story received a major boost when nurse Phyllis Campbell published, in the Occult Review’s August 1915 issue, an account of her own alleged experiences talking to veterans in army hospital. She wrote under the name Phil Campbell. Her nursing memoir “Back to the Front: Experiences of a Nurse” was also published in 1915. Both Campbell and her mother were journalists.

Campbell recounted stories she had allegedly been told by two veterans who claimed to have seen a vision of St George on a white horse, much as he appeared on the English sovereign coin. This was supposed to have happened at Vitry-le-François three weeks after Mons. In his own 1915 publication, Machen critiqued her evidence, which really did not stand up to scrutiny. As Machen pointed out, it was all hearsay – no one could actually produce anyone who admitted to seeing Saint George, angels, or bowmen, or even a shining cloud. It was all at second hand. The image of Saint George clad in little more than a short cloak on the sovereign bore little resemblance to the mighty armoured horseman that people were describing. However, the idea that some supernatural being or beings had intervened on behalf of both the French and English forces – in the case of the French, Joan of Arc – gained even greater traction.

Machen turned out to be the greatest debunker of the legend he believed he had created. As he freely admitted, he had no personal aversion to the possibility of divine intervention in wartime – he retained an open mind on this. This makes sense in terms of his own interests in occultism and mythology. He was simply certain that the legend that became the Angels of Mons entirely derived from his own short story.

Remarkably, people still preferred to believe the legend, and more versions began to appear in print using unsubstantiated reports of clouds, shining, and a company of beings. Machen’s own account was challenged by the author Harold Begbie, who suggested he may have been picking up an actual event by telepathy. One thing was increasingly clear; people promoted the various stories, whether angels, Saint George, or heavenly bowmen, because they so clearly wanted them to be true. Plus, the legend made great material for the press and did nothing to harm morale or recruitment at a critical point in the war. Quite the reverse. When the stories were being promoted as potentially true by the clergy, and by one clergyman’s daughter in particular, Miss Marrable, why would anyone feel the need to disagree with them? These other implications of the popularity of the story were made clear by researcher David Clarke in his in-depth book on the topic.

Divine intervention on the battlefield has a long history. The pharaoh Ramesses II claimed that it was a visitation by the god Amun that gave him and his chariot team strength at a critical point during the battle of Kadesh. According to Plutarch, Brutus the assassin of Caesar was visited by a nameless form before the Battle of Philippi; Shakespeare turned this into a manifestation of Caesar’s ghost. The battlefields of the Wars of the Three Kingdoms rang with the noise of invisible armies and were lit up by ghostly fighting in the clouds, particularly around Christmas Eve. It was towards the Christmas of 1914 that the angels, or shining beings story gained serious momentum. By this time both sides were entrenched, the mobility of the early engagements such as Mons long gone.

The terrible casualty rate of the First World War resulted not only in renewed interest in mainstream religion but also in spiritualism and spiritualist churches. One of the most famous supporters of this reinvigorated spiritualism was Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. As Roger Clarke points out in his “Ghosts: a Natural History”: “Two powerful forces were at work here – the tradition of the English Christmas ghost story and the beginning of a huge revival in spiritualism, just as it seemed about to die out”.

Machen’s original story is very brief, and perhaps better than he rated it. It has humour, shock, and a sense of awe, features that are typical of much of his work. The other stories in his 1915 collection also have supernatural themes but focus much more on the brutality of war and the inhuman behaviour of the German troops. They promote the patriotism that was an essential part of maintaining momentum during the war. Machen’s story “The Soldier’s Rest” has an incident of such brutality that it can be classified with the “mountain of myth [that] grew over the atrocities which the Germans were supposed to have committed”, as historian A.J.P. Taylor described it. “Some of these stories were fabricated by ingenious journalists for want of better material,” concluded Taylor.

Yet Taylor, that most rational and sharp historian of his generation, was sympathetic to the Mons story: “Still, it was the first British battle; and also the only one where supernatural intervention was observed, more or less reliably, on the British side. Indeed, the ‘angels of Mons’ were the only recognition of the war vouchsafed by the Higher Powers”. Taylor knew the real truth of the success at Mons; the rapid fire of the British riflemen had been so intense (and accurate) that the Germans thought it came from machine guns. At “fifteen rounds rapid per minute” from the rifles and only two machine guns per British battalion, this deadly accuracy had delivered the impossible at Mons before the retreat.

If not for the story of the Angels, the Battle of Mons may never have achieved the lasting fame that it has. For some well-known chroniclers of the war such as Basil Liddell Hart, the engagement warranted only a passing reference. It is interesting that despite his attempts to debunk his own story Arthur Machen himself, or his publisher Putnam, used the “Angels of Mons” as part of the title of his 1915 collection of short stories. If it hadn’t been for his own honesty in the introduction of this book, the legend would have maintained greater credibility.#

It’s worth considering the intensity of Machen’s own original vision, too: “In the midst of the flame, consumed by it and yet aureoled in it, scattered like ashes and yet triumphant, martyred and forever glorious”. For much of history people believed that visions were divinely inspired. Many still do. People wanted to believe, and do so today, because the story of the Angels of Mons brought hope, and a sense of glory, in the midst of the reality of death and desolation.

Dr Miriam Bibby FSA Scot FRHistS is a historian, Egyptologist and archaeologist with a special interest in equine history. Miriam has worked as a museum curator, university academic, editor and heritage management consultant.

Published: 24th January 2025.