The smallest of the four main Channel Islands, Sark is located some 80 miles from the south coast of England and only 24 miles from the north coast of France. Not part of the United Kingdom nor the European Union, Sark is reputed to be the smallest independent feudal state in Europe and to have the last feudal constitution in the western world.

Whilst not strictly speaking a sovereign state, under a unique status the Seigneur of Sark, the head of the feudal government, holds the island for the English monarch.

Confused? …well perhaps just a glimpse into the history of Sark will help to explain the unique status of this fascinating little island.

A few worked stone and flint finds testify to early life on megalithic or Stone Age Sark. Still later it appears that the Romans inhabited the island, possibly for a few hundred years or more.

Following the collapse of the Roman Empire, the Dark Ages ensued and with it historical fact gets a little vague. What is known however, is that along with the new faith of Christianity which was spreading across Europe at the time, the missionary St.Magloire arrived in Sark around AD 560. St.Magloire is credited with founding a monastery on the north-west of the island (still known as ‘La Moinerie’), and from there he dispatched his friars to bring the Christian faith to the other Channel Islands.

The monastery survived several raids by pagan Vikings throughout the ninth century until the early 900s when the next generation of Norsemen (now Christianised Norsemen otherwise known as Normans) settled the region. The first Duke of Normandy was Rollo, and it was Rollo’s son William Longsword who took possession of the Channel Islands in 933.

Sark’s long association with the English Crown dates back to 1066 when Guillaume Duke of Normandy conquered England. Guillaume became King William I of England, also known as ‘The Conqueror’. Although he was now king of England, William also retained his position as Duke of Normandy.

Later, when King John of England lost Normandy to King Philip II of France in the early 1200’s, the Channel Islands remained loyal to the English crown. In return for this loyalty, King John granted the islands certain rights and privileges which allowed them to be virtually self-governing.

Over the next few centuries, the Channel Islands were subject to many murderous French raids; the Sark community however weathered these stormy times and by 1274 Sark had a population of about 400, mostly involved in farming, fishing and other ‘less legal’ shipping occupations.

It is thought that the Black Death was responsible for ending the long period of continuous habitation of Sark, around 1348.

The strategic importance of Sark’s location in the Channel meant that over the next few hundred years it was always the subject of close attention, a fact that was particularly influenced by the status of Anglo-French relations at that time. In 1549 a French naval force of 400 men landed on the island and established fortifications: they were eventually expelled.

The fear of further French occupation led to Sark being permanently settled again in 1565 by the Seigneur of St Ouen from nearby Jersey, Helier de Carteret. Together with his wife and several of their St Ouen tenants, the Heliers moved onto the island.

Helier’s role was to ensure that Sark would never again become depopulated and could rise, when required, to defend itself. To achieve this he parcelled the land up into sections, each large enough to support a family and charging a peppercorn rent, he leased each parcel. Strict tenancy agreements stipulated that a house must be erected on each parcel of land and each tenant was required to provide a man, armed with a musket and ammunition, to defend the island when called to do so.

In 1565 Queen Elizabeth I rewarded Helier by granting him the feudal title of fief, with an obligation to maintain 40 households and men with arms to defend the island and to pay the Crown the twentieth part of a knight’s fee annually for the privilege – in today’s money that is about £1.79! This royal recognition formally established the constitutional basis which survives on Sark to this present day.

The first forty tenants came mainly from Jersey, many were either friends or family, but all were united by the strict Presbyterian faith. Helier’s settlers brought with them Jersey laws and customs and Sark’s first parliament, known as the Chief Pleas, met in November 1579.

With royal approval, the ownership of Sark changed several times during the early 1700s until in 1730 it was purchased by Susanne Le Pelley, the widow of a prominent Guernsey privateer. It was also around this time in history that the effects of the revolution in nearby France began to lap the shores of the island. The Le Pelley family however appear to have responded well to any anti-feudal sentiment by launching several public projects including the building of a free school.

During the Napoleonic Wars new canon began to appear along the cliffs tops of Sark, and the dutiful tenants kept to the terms of their tenancy agreements by organising night time vigils with arms at the ready to repel any attempted French invasion.

The Industrial Revolution appears to have arrived in Sark in 1833 with the discovery of copper and silver deposits; this led to the formation of the Sark Mining Company. To finance the venture the Seigneur mortgaged the island with the hope of finding lucrative veins of ore. 250 Cornish miners duly arrived, along with all the equipment necessary to extract the precious minerals. Those lucrative veins were never found however, and the mines were eventually abandoned in 1847 leaving the Seigneur in serious debt.

Unable to afford the mortgage, the Le Pelleys sold the fief of the island to the Collings family with the Reverend W.T.Collings becoming the new Seigneur in the early 1850s. Rev. Collings embarked upon a substantial building programme which included adapting Creux harbour to accommodate the new steam boat service from Guernsey. With this, the economy of Sark changed almost overnight as the first tourists began to arrive, staying at the newly built hotels and admiring the local scenery including the Seigneurie’s once private gardens.

During World War II, Sark was occupied by German forces between 3rd July 1940 and 10th May 1945. Perhaps due to its relatively small size and traditional reliance on agriculture and fishing, the islanders appear to have suffered less than they did on the larger of the Channel Islands.

With the arrival of the 21st century, feudal Sark is now being forced to adapt. In coming to terms with international Human Rights legislation, major amendments have already been made to its inheritance and tax laws, and radical constitutional and administrational changes are gradually being introduced.

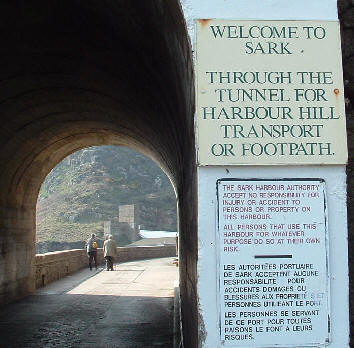

Visitors to modern-day Sark however would hardly notice the impact of the radical changes and reforms taking place. With no airstrip, no motor cars or tarmac roads, life on Sark remains visibly unaffected by modern life, and, perhaps it is because personal transportation is restricted to foot, bicycle or horse drawn carriages that the pace of life appears more congenial and relaxed.

The islanders themselves now welcome all, or almost all, to share in their haven. French invaders, or tourists as they are called, arrive constantly throughout the summer months via the local Guernsey – Sark ferry. Less welcome it seems are the more local noisy neighbours from London who have taken up residency on a nearby island. It appears that their lack of popularity is due in part to their desire to change the traditional agricultural face of Sark.