The six and a half centuries between the end of Roman rule around 410 and the Norman Conquest of 1066, represent the most important period in English history. For it was during these years that a new ‘English’ identity was born, with the country united under one king, with people sharing a common language and all governed by the laws of the land.

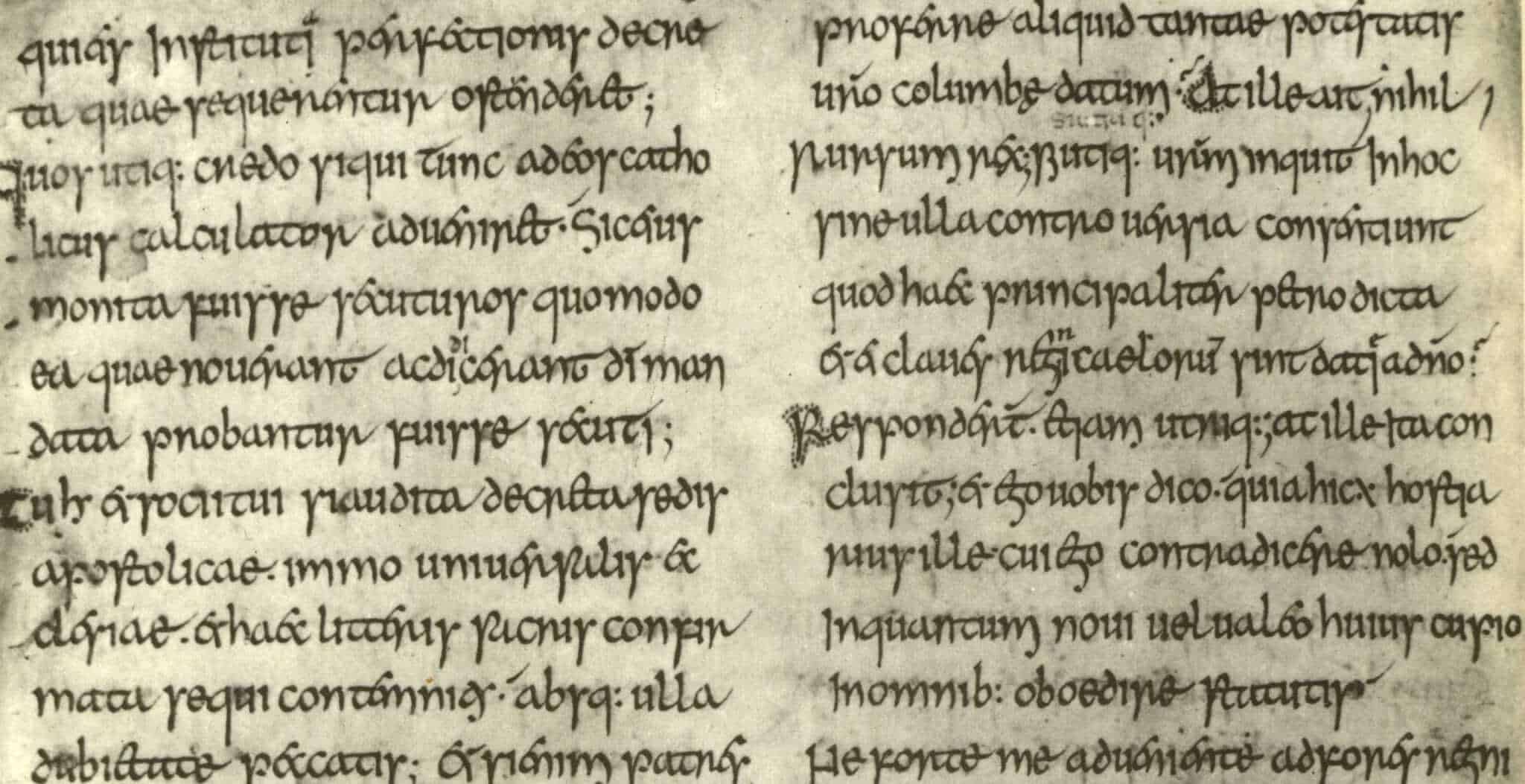

This period has traditionally been labelled the ‘Dark Ages’, however it is between the fifth and early sixth centuries that can perhaps be called the ‘Darkest of the Dark Ages’, as few written records exist from these times and the ones that do are either difficult to interpret, or were documented long after the events they describe.

The Roman legions and civilian governments began to withdraw from Britain in 383 to secure the Empire’s borders elsewhere in mainland Europe and this was all but complete by 410. After 350 years of Roman rule the people left behind were not just Britons, they were in fact Romano-Britons and they no longer had an imperial power to call upon to protect themselves.

The Romans had been troubled by serious barbarian raids since around 360, with Picts (northern Celts) from Scotland, Scots from Ireland (until 1400 the word ‘Scot’ meant an Irishman) and Anglo-Saxons from northern Germany and Scandinavia. With the legions gone, all now came to plunder the accumulated wealth of Roman Britain.

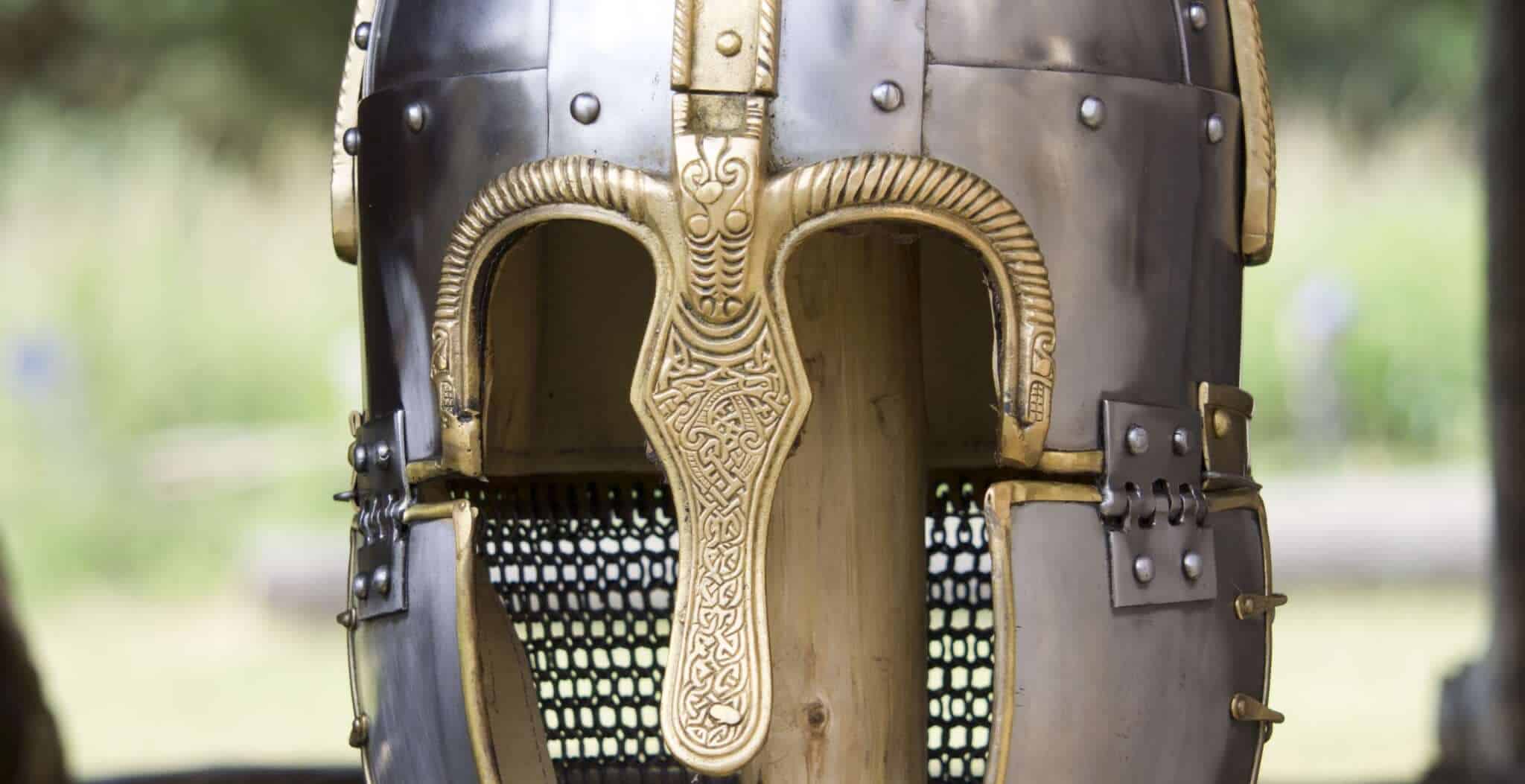

The Romans had employed the mercenary services of the pagan Saxons for hundreds of years, preferring to fight alongside them rather than against these fierce tribal groups led by warrior-aristocrats under a chieftain or king. Such an arrangement probably worked well with the Roman military in place to control their numbers, using their mercenary services on an ‘as required’ basis. Without the Romans in place at the ports of entry to issue visas and stamp passports however, immigration numbers appear to have got a little out of hand.

Following earlier Saxon raids, from around 430 a host of Germanic migrants arrived in east and southeast England. The main groups being Jutes from the Jutland peninsula (modern Denmark), Angles from Angeln in southwest Jutland and the Saxons from northwest Germany.

The chief ruler, or high king in southern Britain at the time was Vortigern. Accounts written sometime after the event, state that it was Vortigern who hired the Germanic mercenaries, led by brothers Hengist and Horsa, in the 440s. They were offered land in Kent in exchange for their services fighting the Picts and Scots from the north. Not content with what was on offer, the brothers revolted, killing Vortigern’s son and indulging themselves with a grand land grab.

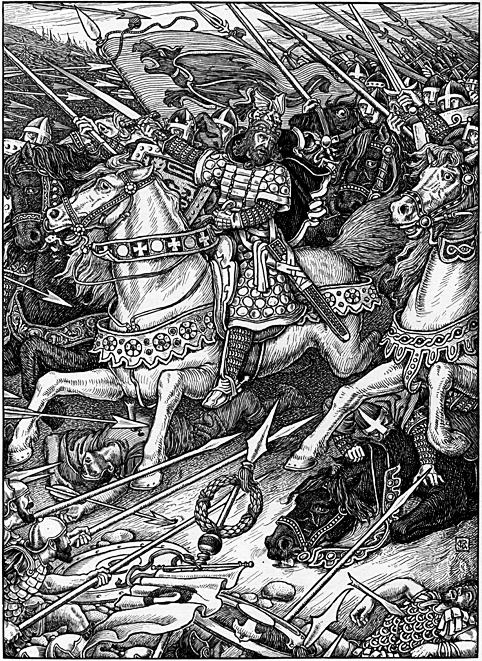

The British cleric and monk Gildas, writing sometime in the 540s, also records that Britons under the command of ‘the last of the Romans’, Ambrosius Aurelianus, organised a resistance to the Anglo-Saxon onslaught which culminated at the Battle of Badon, aka the Battle of Mons Badonicus, around the year 517. This was recorded as being a major victory for the Britons, halting the encroachment of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms for decades in southern England. It is during this period that legendary figure of King Arthur first emerges, although not mentioned by Gildas, the ninth-century text Historia Brittonum ‘The History of the Britons’, identifies Arthur as the leader of the victorious British force at Badon.

By the 650s however, the Saxon advance could be contained no more and almost all the English lowlands were under their control. Many Britons fled across the channel to the appropriately named Brittany: the folk who remained would later be called the ‘English’. The English historian, the Venerable Bede (Baeda 673-735), describes that the Angles settled in the east, the Saxons in the south and the Jutes in Kent. More recent archaeology suggests that this is broadly correct.

At first England was divided into many little kingdoms, from which the main kingdoms emerged; Bernicia, Deira, East Anglia (East Angles), Essex (East Saxon), Kent, Lindsey, Mercia, Sussex (South Saxons), and Wessex (West Saxons). These in turn were soon reduced to seven, the ‘Anglo-Saxon Heptarchy’. Centred around Lincoln, Lindsey was absorbed by other kingdoms and effectively disappeared, whilst Bernicia and Deira combined to form Northumbria (the land north of the Humber).

Over the centuries that followed the borders between the major kingdoms changed as one gained ascendancy over the others, principally through success and failure in war. Christianity also returned to the shores of southern England with the arrival of Saint Augustine in Kent in 597. Within a century the English Church had spread throughout the kingdoms bringing with it dramatic advances in art and learning, a light to end the ‘Darkest of Dark Ages’.

By the end of the seventh century, there are seven main Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms in what is today modern England, excluding Kernow (Cornwall). Follow the links below to our guides to the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms and monarchs.

• Northumbria,

• Mercia,

• East Anglia,

• Wessex,

• Kent,

• Sussex and

• Essex.

It would of course be the crisis of Viking invasion, however, that would bring a single unified English kingdom into existence.