Is William Blake’s ‘Jerusalem’ a patriotic expression of Englishness – or a parody of the nationalistic fervour of the Napoleonic War era?

This poem is best known as the hymn “Jerusalem”, with music written by Sir Hubert Parry and orchestration by Sir Edward Elgar.

“And did those feet in ancient time

Walk upon England’s mountains green?

And was the holy Lamb of God

On England’s pleasant pastures seen?

And did the Countenance Divine

Shine forth upon our clouded hills?

And was Jerusalem builded here

Among these dark Satanic Mills?

Bring me my bow of burning gold!

Bring me my arrows of desire!

Bring me my spear! O clouds, unfold!

Bring me my chariot of fire!

I will not cease from mental fight,

Nor shall my sword sleep in my hand,

Till we have built Jerusalem

In England’s green and pleasant land.”

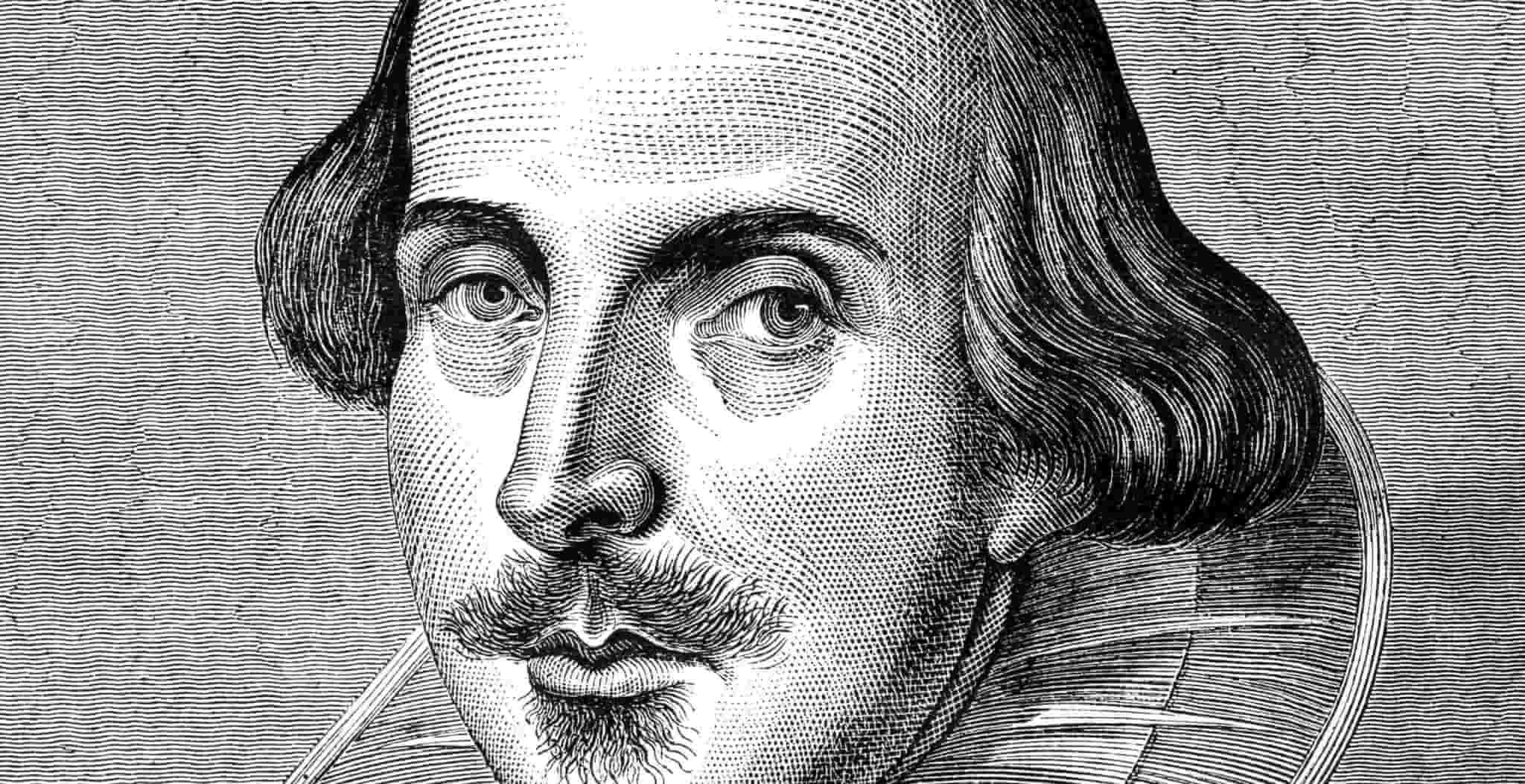

William Blake wrote these emotive words around 1804, originally as a preface to his epic work Milton, a Poem. In 1916 Hubert Parry took these lines and set them to music during the dark days of World War I, when the nation looked to music to help raise morale.

Students of Blake’s work will be well acquainted with the almost deliberate ambiguity that leaves much of his poetry open to interpretation, and the same can be said of ‘Jerusalem’. To better understand the poem, it is necessary to look at the man behind the words, the poet himself.

The irony is that Blake was not a nationalist but a revolutionist. He was even arrested for sedition in January 1804 but later acquitted.

You could even argue that Blake wrote ‘Jerusalem’ as a parody of nationalism, for this was the era of revolution: the American Revolution of 1775 and the French Revolution of 1789. Fears of French invasion were rife in England in the early 1800s, indeed the government were even fearful of home-grown revolution.

Blake was a radical who championed the poor and oppressed. He was anti-monarchy, anti-organised religion, anti-industrialisation and anti-establishment. To quote the book ‘1066 and All That’, he saw the French Revolution as a ‘Good Thing’.

With this in mind, let us consider the poem: what do Blake’s words actually mean?

In the first verse, Blake asks did the Lamb of God – Jesus – walk upon England’s pastures green. This alludes to the ancient legend that Joseph of Arimathea visited England with the Holy Grail and founded a church here. The legend continues that as Joseph climbed Wearyall Hill near Glastonbury, he thrust his staff into the ground to lean upon it to rest. According to the legend a thorn tree sprang up from this place which unusually flowered twice a year. A thorn tree said to be descended from a cutting from the original tree can be found in the grounds of Glastonbury Abbey today. Blake invites the answer ‘no’ to this question.

The second verse refers to Jerusalem:

“And was Jerusalem builded here

Among these dark Satanic Mills?”

It is likely that Blake is referring here to the biblical Jerusalem in the Book of Revelation, a city of light. As Blake’s England is dark, smoky and increasingly industrial, the answer here again is ‘no’.

The phrase, ‘dark Satanic Mills’ in this verse is open to interpretation.

Of course they may simply refer to the mills of the Industrial Revolution. Blake was a radical who championed the poor. In his opinion the mill owners enslaved their workers, depriving them of their liberty. Blake feared the rise of industrialisation and its impact on society.

A second interpretation is that the ‘Mills’ may refer to churches. Blake disliked institutionalised religion which he considered part of the establishment, the oppressor of the people.

A third interpretation is that the ‘Satanic Mills’ may refer to the universities of Oxford and Cambridge, the enslaving ‘mills of the mind’, stifling free thought.

The third verse makes reference to ‘chariots of fire’. This may refer to the story of the prophet Elijah in the Old Testament, who ascends to heaven in a chariot of fire.

“I will not cease from mental fight,

Nor shall my sword sleep in my hand,

Till we have built Jerusalem

In England’s green and pleasant land.”

Is this the revolutionist Blake, calling for a people’s revolt, to free the poor from tyranny, end industrialisation and return to a land of peace and harmony in a utopian England? Or is he just asking us to strive to build a better England, a green and pleasant land of peace?

Today ‘Jerusalem’ is considered to be a patriotic expression of Englishness, a permanent fixture at the Last Night of the Proms and adopted by such diverse groups as the W.I., the Labour party and England rugby fans. At face value this is perhaps true, but it may instead have actually been intended to be a parody of the nationalism fervour of the Napoleonic War era, in which case it is really quite ironic.

Published: 1st September 2025