By the 18th century, coffee houses were commonplace in England, with some requiring payment to enter and sometimes, admittance only by invitation or membership. In return customers would receive in varying degrees of quality, coffee, food and perhaps entertainment or some other focus. The Georgian period (1714-1830) saw great vibrancy bringing developments in science, technology, art, literature and perhaps above all, ideas.

During that time, Birmingham was a place where things were happening and fast. The population of the town had increased to an extent that it became the third most populous in Britain and was a centre of innovation and enterprise for industry and business.

New societies and groups formed along specific lines such as trade, science and commerce. One of the best known was the Lunar Society (so named because it met on evenings when a full moon would provide light to guide its members homeward). Members included notable scientists and industrialists such as: James Watt, Josiah Wedgwood, Erasmus Darwin, Matthew Boulton and Joseph Priestley. The society met in the dining room at Soho House, the grand home of Boulton located two miles from the town centre but other groups, particularly those comprising less affluent members, would often gather in public establishments such as inns and coffee houses.

John Freeth (1731-1808) aged around 59 years. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license

John Freeth (1731-1808) aged around 59 years. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license

John Freeth is only occasionally mentioned in more authoritative history books, but his life is a story of an ordinary man who made his mark within local society and sometimes beyond. His early life is not well recorded but it is believed he had been a brass foundry apprentice and upon the death of his parents, he took over as landlord of the Leicester Arms (already known alternatively as a coffee house) on the corner of Bell Street and Lea Lane around 1768. He remained there until his death in 1808.

It is likely that John grew up in a liberal home environment as the ‘coffee house’ was already known as the meeting place of the Reading Society and may well have been the forerunner of the Birmingham Book Club, which in turn provided the nucleus of subscribers to the Birmingham Library. The spread of knowledge through the discussion of ideas was a fundamental characteristic of the Freeth establishment.

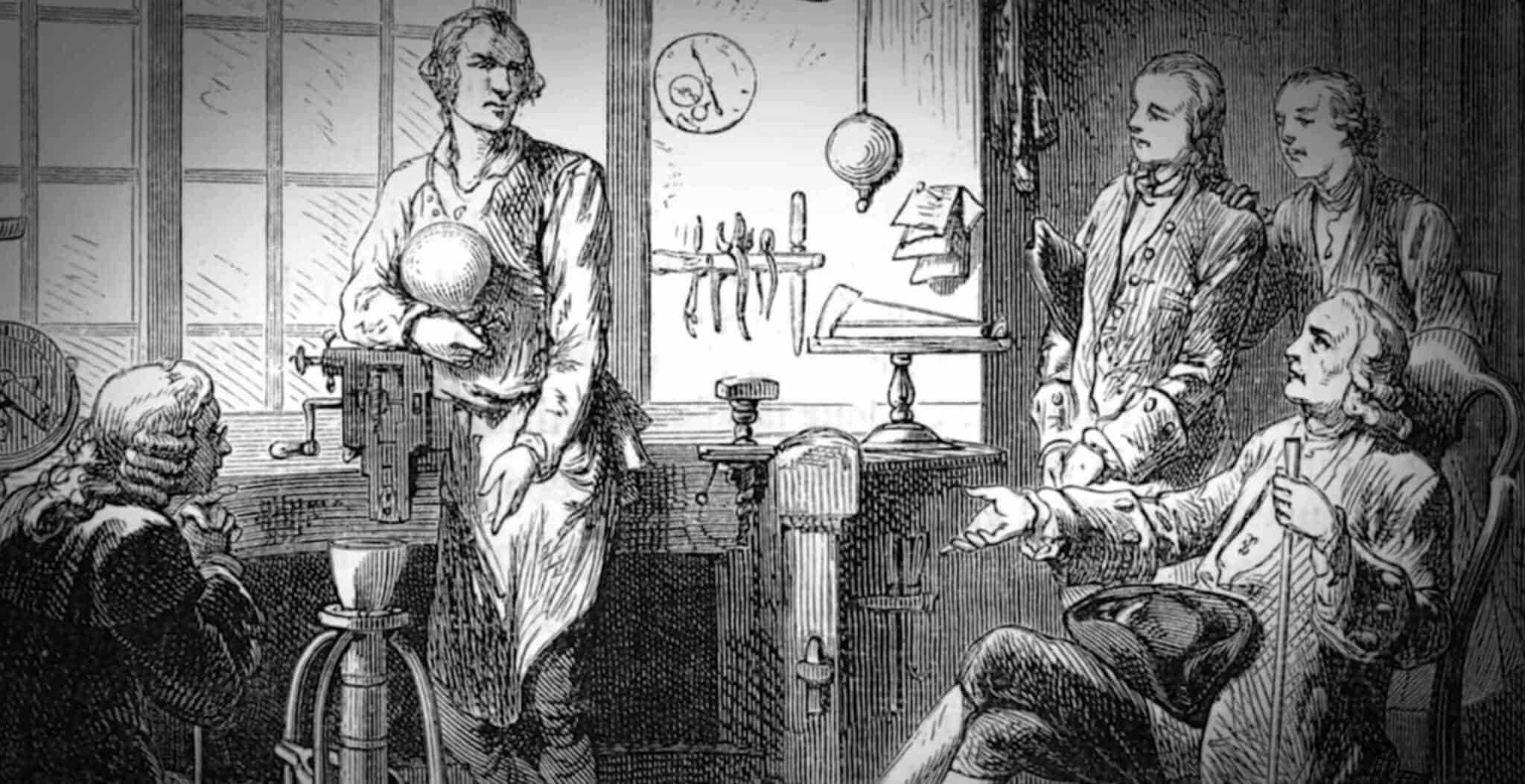

His interest in life was widespread and at one point he offered himself as a teacher of ‘the Science or Doctrine of Geography, with the knowledge and use of the Celestrial and Terrestrial Globes’. It is not clear what qualification Freeth had for making such an offer and is probably more a reflection of growing confidence and general desire within society for self-improvement and scientific development.

Freeth was certainly a great self-publicist and had invitation cards printed with the heading Society Feast advertising his coffee house as the venue for poetry, politics and dinner, usually with an enticing reference to a particular topical issue of the day such as the price of bread, or the trial of Warren Hastings, Governor-General of Bengal who faced an impeachment trial for corruption and mismanagement.

Around 1760 Freeth began to write ballads and perform them in public. Shortly after he began publishing them in short books with such titles as ‘The Political Songster’. Over the following years he published several more with that title as well as A Touch of the Times, A Collection of New Songs and The Warwickshire Medley among others. Interestingly, no original music was written, but each poem was usually listed alongside a suggested well known tune of the time to which Freeth’s lines could be delivered.

Not for him were the gruesome tales of murders, rapes, or hangings as subjects of interest. A radical and a liberal, politics was the core of his output covering feats of war, affairs of state, riots, the budget, elections, national emergencies and the activities of politicians as he saw fit to report them, usually with a clear and deliberate absence of impartiality.

Freeth’s own political sympathies were as a supporter of the Whig party which opposed the government of Lord North and he grew increasingly sympathetic to the American colonists in their dispute with the British government. Freeth also took up the cause following the imprisonment of the radical journalist and politician John Wilkes, who had been gaoled on the grounds of sedition and libel, published in his journal The North Briton. Despite successfully standing for election three times, the House of Commons overturned the results. Eventually released, he became an MP and Freeth celebrated the event with his fellow club members.

Like many coffee houses, Freeth’s became a venue for formal and informal groups which shared a political leaning. One such group was the Jacobin Club whose local members included among others, a brass-founder, surgeon, lamp manufacturer, publisher, tin merchant, cheese factor and of course, John Freeth. Jacobins tended towards progressive ideas such as the Reform Bill and Catholic Emancipation, as well as generally promoting sentiments of liberty but remaining loyalists.

The Jacobin Club. Freeth is third from the left, clay pipe in his mouth

The Jacobin Club. Freeth is third from the left, clay pipe in his mouth

Members of the Jacobin Club commissioned a painting which hung at Freeth’s coffee house and was held on the tontine principle (last man standing shall own it). One Tory wit described those in the picture as ‘the twelve apostles’.

The nearby Minerva Tavern hosted meetings of those aligned with the Tories and very much opposed the ideas promoted by the Jacobins. A sign over the fireplace there proclaimed ‘No Jacobin Admitted Here’.

In 1791, riots broke out in Birmingham aimed at Protestant dissenters who rejected the established Church of England. Lunar Society member and dissenter Joseph Priestley, was one of many primary targets and his house was destroyed by a violent mob.

The riots took place over three days and despite the Leicester Arms being located within the general area of the riots, no reference by Freeth has been found to the acts of violence which took place over three days. Perhaps he was fearful that any criticism could result in a threat to his own establishment where liberal ideas were openly discussed.

The journalist and novelist William Godwin passed through Birmingham in 1797 and saw a hand-bill advertising a waxworks exhibition which, it said contained a likeness of Freeth. He wrote to his wife Mary Wollstonecraft:

“As I had never heard of poet Freeth, my curiosity was excited. We found that he was an ale-house keeper of Birmingham, the author of a considerable number of democratical squibs. If we return by Birmingham, I promise myself to pay him a visit”.

By the time Freeth died aged 77 in 1808 he had been the landlord for almost forty years and his passing was recorded in Aris’s Birmingham Gazette as ‘of this town, commonly called the Poet Freeth, a facetious bard of nature’. He was described as a man whose morals were unsullied and manners unaffected. It was said that the inscription on his tombstone had been written by Freeth himself and read:

A measure of his local status was perhaps demonstrated by a portrait of Freeth which was posthumously funded through public subscription and displayed for a time in the coffee house, the site of which today lies buried beneath the modern Bull Ring Shopping Centre.

But for all of Freeth’s political and social output, he would perhaps wish to be remembered first and foremost as a Brummie. Even the important events of the day would never prevent him from praising his home town:

By William Philpott. Now in retirement following a career in social housing, William has embarked on researching and writing about one of his life-long interests, modern political history.