Fairies were complex and problematic creatures in early modern England. The Catholic Church had condemned them as demonic spirits, the law courts had subsumed fairy belief with black magic and witchcraft, and successful playwrights, authors and poets, including William Shakespeare and Edmund Spenser, had made them the protagonists of their works. Despite this conflict, there was a particular fairy, a spirit called Robin Goodfellow, whose existence withstood the contemporary attacks on folklore beliefs and continued to cause mischief in sixteenth and seventeenth-century households.

Goodfellow was, as far as historians are aware, a native British spirit who personified the medieval character of the ‘Puck’. His unusual name reflected the popular reference to fairies as the ‘good people’, which symbolised their love of flattery despite their mischievous nature. In the aftermath of the Protestant Reformation, as with other supernatural beings, Goodfellow became the subject of negative texts written by Protestant polemicists. Reginald Scot referred to him as the ‘great and ancient bullbeggar’, Edward Dering blamed him for the ‘idle superstitions’ of medieval religion and Edmond Bicknoll claimed he was born from the ‘fruit of infidelity’ and was a conspirator of the devil. However, contrary to the attacks from Protestant authorities, the belief in Robin Goodfellow and his fairy companions remained significant in early modern popular culture, particularly in the household.

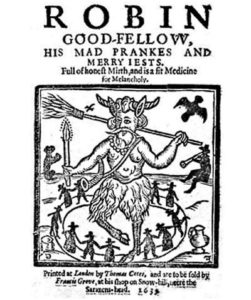

Goodfellow’s homeland Oberon, or ‘Fairyland’, was described as a land free from vice and disorder, thus he was believed to be fanatical about imposing control on the mortal world through promoting cleanliness and a strong work ethic. For example, it was believed that fairies could help tidy the home; hence Goodfellow was often depicted carrying a broom and supporting domestic workers with their chores. It was also understood that he could enforce order on the household by punishing idle maids who did not meet his high expectations through pinching and nipping them. Consequently, Goodfellow was often praised, or indeed feared, as the strict disciplinarian of the home and its workers.

![]()

Punishments or contracts with fairies formed a significant part of Goodfellow’s purpose on earth. While he could issue good fortune and support, this was always at the cost of those involved. As Reginald Scot commented, Goodfellow had a ‘standing fee’ of a ‘mess of white bread and milk’, which he expected after supporting housewives with their chores. If his payment was forgotten, Goodfellow was believed to steal from the home that owed him, often stealing grain and milk from the dairy.

In addition, in 1628 an anonymous author published a pamphlet from the perspective of Goodfellow and his fairy companions. The pamphlet stated that ‘if we find clean water and clean towels, we leave them money’, however if these gifts have been forgotten, ‘we wash our children in their pottage, milk, or beer, or what-ere we find’. The punishment for neglecting the demands of the fairies continued, ‘we do not only punish them with pinching, but also in their goods, so that they never thrive till they have payd us’.

Fear of the fairies arguably led to a range of customs which were designed to prevent fairy-punishments from occurring. For example, people would often leave out pails of water for the creatures to bathe in and a saucer of milk and bread to appease their appetite. Over a century later in 1731, George Waldron argued that this belief was still important. He contended, ‘a person would be thought impudently profane’ to go to bed ‘without having first set a tub, or pail full of clean water’, in order for ‘these guests to bathe themselves in’.

Robin Goodfellow was also renowned for playing practical, and sometimes cruel, jokes. In 1625, Ben Jonson published a ballad from Goodfellow’s perspective which described some of his favourite ways to cause mischief. The song proclaimed that he had been sent from Oberon to play pranks in the human world. He is portrayed as a lively trickster that could shape-shift to confuse the people he encountered, stating ‘sometimes I meet them like a man, sometimes an oxe, sometimes a hound, and to a horse I turn me can’. His antics ranged from ruining dinner parties by teasing guests, haunting people in their sleep and swapping human children for deformed elf-changelings (a particularly horrific fairy pastime).

The religious context of the early modern period ensured that this was a dangerous time for the belief in spirits and the supernatural, yet it is evident that faith in these creatures remained significant in popular understanding and folklore. Fairies could clean your home and keep your servants in check, however they were also used to explain mysterious events, were blamed for causing illnesses in children, and would steal food and water. Consequently, the range of acts that Robin Goodfellow was responsible for, as well as his ability to simultaneously help and harm made him a problematic, yet incredibly interesting, creature in the early modern world.

By Abigail Sparkes, recent MA graduate in Early Modern History, freelance writer and humanities teacher.