“There are fairies at the bottom of our garden,” announces the opening line of a poem by Rose Fyleman first published in 1917. Coincidentally, that was also the year that two intelligent and talented young conspirators managed to convince the world that there were fairies living near Cottingley Beck, the stream that ran past the foot of their garden.

The curious tale of the Cottingley Fairies began in the summer of that year, when nine-year-old Frances Griffiths and her mother returned to England from South Africa to stay with the Wright family in Cottingley, West Yorkshire. Next to the house where Polly and Arthur Wright and their sixteen-year-old daughter Elsie lived was the small wooded valley through which Cottingley Beck flowed. Elsie and Frances were cousins.

Cottingley Beck still flows picturesquely over rocky outcrops overshadowed by trees, just the type of pretty location that children love to explore. It quickly became the favourite spot of the two cousins, who regularly got into trouble for returning home wet and untidy after playing in and around the beck.

When told off for getting wet, they said they went there “to see the fairies”. Their families undoubtedly scoffed at an excuse that was as thin as “the dog ate my homework”, and so Elsie borrowed her father’s Midg quarterplate camera and went in search of proof. The girls were back within the hour.

Elsie’s father Arthur was a keen amateur photographer with his own darkroom and all the equipment required to develop the plate the girls had taken. The image, now a very famous one, shows Frances, head slightly tilted, gazing off just to the right of the photographer. In front of her several winged fairy figures dressed in diaphanous clothing are dancing. Frances looks as though she is trying hard not to laugh.

Elsie had an interest in photography herself, a talent for art and experience in retouching photographs. Arthur Wright was immediately suspicious. Even when the girls came back in September with an impressive plate showing Elsie holding out her hand to a gnome-like winged figure, Arthur was unconvinced. He knew the girls had been up to something, he just wasn’t sure how they’d done it. The most likely explanation seemed to be that they’d used cut-out figures. Arthur’s instincts were right, though it would be decades before that was confirmed.

Elsie’s mother Polly, who was interested in the Theosophical movement, took the photographs along to a meeting of the Theosophical Society in nearby Bradford. Appropriately, the subject of the evening lecture was “fairy life”, and the images appear to have caught the imagination and the enthusiasm of the society’s supporters, and of one of its leading members, Edward Gardner.

Seizing on an opportunity to promote the most important spiritual message of the Theosophists – that humankind was undergoing a process of transformation that would lead eventually to the perfection of the species – Gardner claimed the two images were supernatural proof that great metaphysical changes were happening.

The photographs were examined by photographic expert Harold Snelling, who confirmed them as authentic images of “what was in front of the camera”, thus avoiding having to validate them as images of fairies. Gardner used the images in his lectures and also had prints created to sell afterwards. The images appeared in a spiritualist magazine where they caught the eye of Sir Arthur Conan-Doyle, a believer in spiritualism himself. He was about to write a piece on fairies for the Christmas edition of the Strand magazine, and asked Arthur and Elsie for permission to use the images.

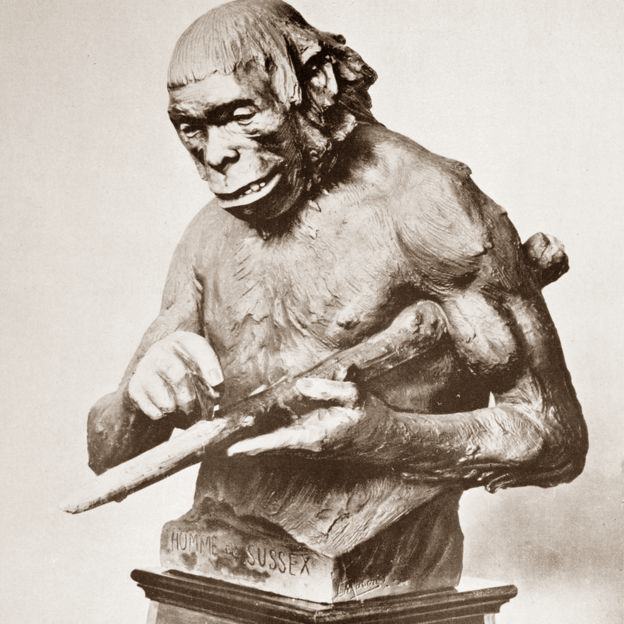

Conan-Doyle’s credulity in this and other matters still remains a mystery. He had been apparently fully taken in by the Piltdown Man fake, and since neither Piltdown Man nor the Cottingley fairies would be revealed as fakes until after his death, he presumably went on believing in the truth of them until the day he died.

For the Cottingley fairies were fakes, beautifully drawn images of fairies probably created by Elsie and staged and photographed by both girls. They had been copied from images in “Princess Mary’s Gift Book”, published in 1914, and then had wings added to them. Held upright with hatpins, they were sufficiently plausible to be accepted by Conan-Doyle and many others. Three more fairy images were taken, the final one, “Fairies and their Sunbath”, in 1920.

Perhaps the timing had something to do with the way the images were so readily accepted. The horrific reality of the 1914-1918 war would leave people desperate for a different world, a world in which there might still be the possibility of magic. Conan Doyle’s own son was a victim of the war.

During the 1920s and 30s, fairies, gnomes and other supernatural creatures would be popular subjects for mass-market prints, pottery and ornaments. As cinematography advanced, the fairy-tale cartoons of Walt Disney captured the imagination of children and adults alike. People continued to believe in the fairies because they wanted to believe in them. They wanted to have faith in the girls and the story they told. Somewhere in a forgotten corner of the green and pleasant isle, supernatural beings still lived their secret lives, revealed only to a select few.

Hard though it is to believe now, debate on the authenticity of the Cottingley fairies continued until well into the 1960s. Television opened up even greater opportunities for investigative journalism in the following decade, and the images came under greater scrutiny. However, they were not entirely debunked until the 1980s, when Geoffrey Crawley, the editor of the “British Journal of Photography”, undertook a major investigation, concluding they were fakes.

The cousins were both still alive in the 1980s, and finally Elsie confessed to the hoax, probably with some relief, in 1983. What had undoubtedly started out as a cleverly stage-managed bit of fun, suggested by Frances, had got seriously out of hand. The cousins themselves were astonished at how readily people of the calibre of Conan-Doyle had accepted the images. Perhaps not wholly wanting to relinquish the story, Frances maintained all her life that “Fairies and their Sunbath”, the fifth and last image, showed real fairies, not fakes.

Miriam Bibby BA MPhil FSA Scot is a historian, Egyptologist and archaeologist with a special interest in equine history. Miriam has worked as a museum curator, university academic, editor and heritage management consultant. She is currently completing her PhD at the University of Glasgow.