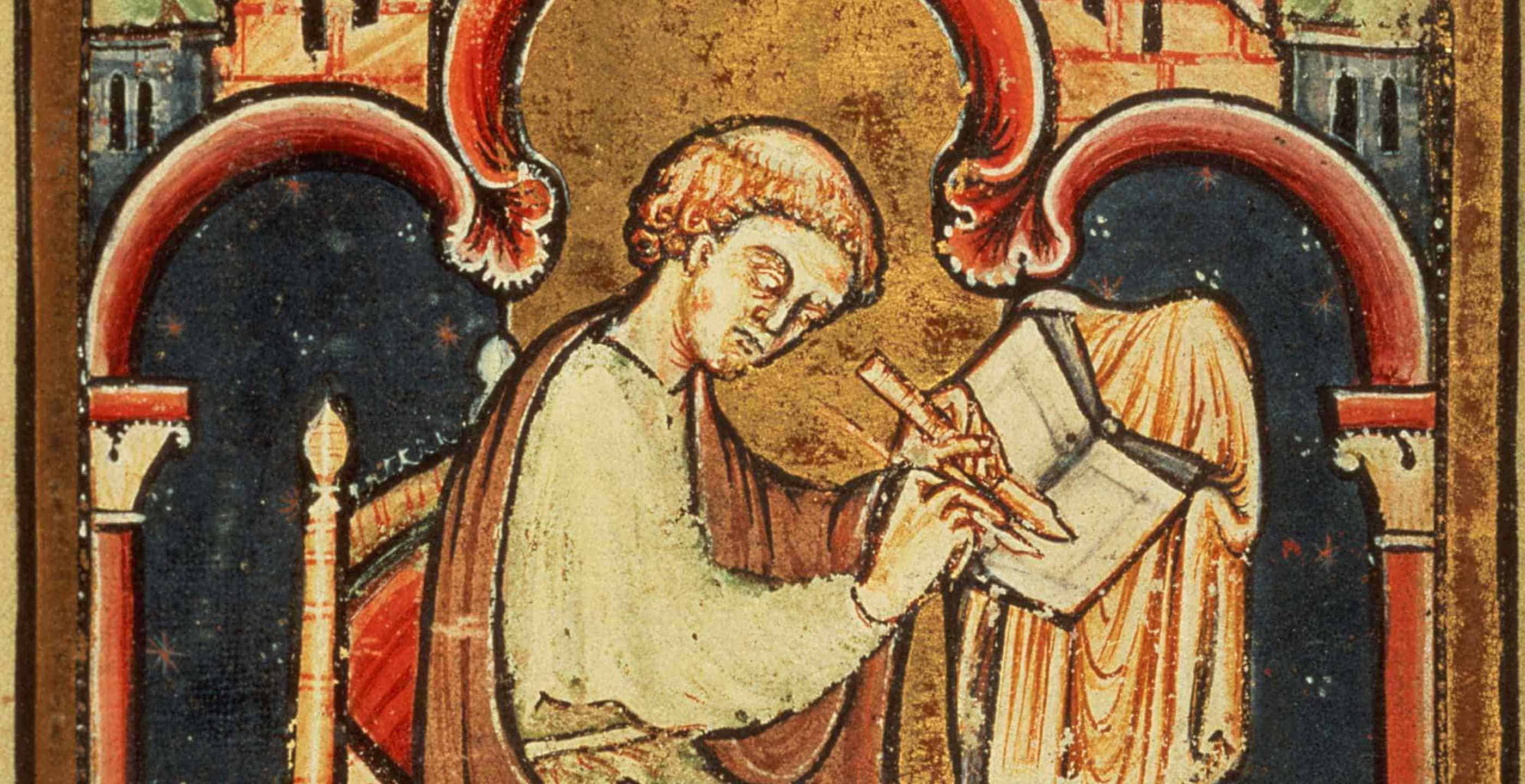

Christmas Day celebrations in Britain have a long history, with the first recorded date of Christmas in England in the year 597 when Augustine baptised 10,000 Saxons in Kent on Christmas Day.

As the message of Christianity continued to spread, the number of worshippers increased, including significant royals of the British Isles.

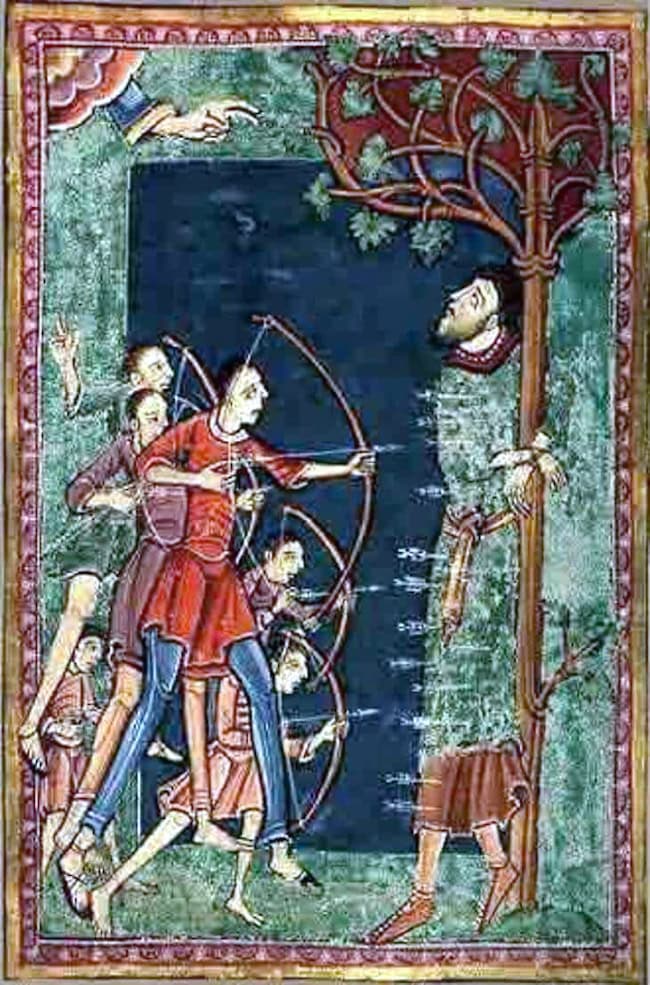

Edmund the Martyr, who later became patron saint of England, was crowned King of East Anglia on Christmas Day in 855. Whilst his reign ended in his brutal killing by the heathen Danish army, his refusal to renounce his faith saw subsequent English kings take St Edmund as their patron, establishing a proud Christian tradition of royalty.

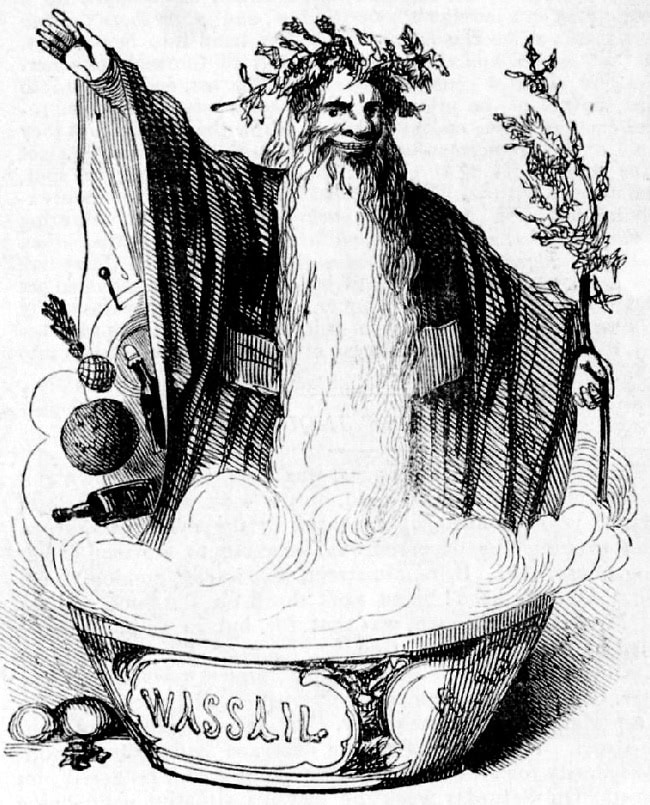

Subsequently another famous royal who defended his lands from the Vikings was Alfred, King of Wessex (also known as Alfred the Great). During his reign he called for the Twelve Days of Christmas to be celebrated and to mark the occasion, announced that no work should be done during this time. The origins of Wassailing, that ancient Twelfth Night tradition, dates to this time with the phrase ‘waes hael’ meaning ‘good health’ in old Saxon.

In 1066, after defeating King Harold II at the Battle of Hastings, William the Conqueror ushered in a new era of Norman domination and was significantly crowned at Westminster Abbey on Christmas Day.

As Christianity continued to spread, so too did its influence on the royals. In 1095 a new royal was born, the future King Stephen, named after St Stephen, the first martyr of Christianity.

In Medieval England, Christmas became an important celebratory period and was marked by formal state occasions and ceremonies. During his 34-year reign, King Henry II held Christmas ‘crown-wearing’ at 24 separate locations.

In 1116 Christmas became a double celebration for Henry II, when his second son John was born on Christmas Day.

He also famously celebrated Christmas in 1171 at his ‘winter palace’, which was constructed outside Dublin’s city walls after his successful invasion of Ireland. The setting proved to be perfect for an elaborate feast and raucous celebrations which lasted for several months.

These winter festivities included copious amounts of food and delicacies previously unseen in Ireland, including the flesh of a crane as well as peacocks, swans, heron and wild geese which were all consumed in great quantities by the king.

Upon the death of Henry II, his famous son Richard the Lionheart, known for his escapades abroad during the Crusades, inherited the throne.

When Richard the Lionheart died, his younger brother John became king and reigned over a disastrous period of instability, characterised by his unpopularity due to heavy taxation, the disintegration of his father’s empire and disputes with the Church.

During his reign, King John would host many lavish feasts at Christmas, with vast amounts of food including 15,000 herrings and 420 boars heads for his festive celebrations in 1213.

A year later, his celebrations were far more subdued, as his unpopular reign and falling out with his noblemen saw him dine alone. Such events became the subject of a poem by A.A Milne (best known for Winnie the Pooh) entitled ‘King John’s Christmas’.

King John was not a good man,

And no good friends had he.

He stayed in every afternoon …

But no one came to tea.

And, round about December,

The cards upon his shelf

Which wished him lots of Christmas cheer,

And fortune in the coming year,

Were never from his near and dear,

But only from himself.

By the Middle Ages, the Christmas feast had well and truly come into its own. Due to the expense of feeding livestock in the chilly winter months, large numbers of them were killed to be eaten. For King Henry III in 1264, his Christmas feast which was celebrated at Woodstock Palace, consisted of no fewer than 30 oxen, 100 sheep, five boars, salted venison from Wiltshire, nine dozen fowl and salmon as well as copious amounts of alcohol.

Aside from the lavish feasts, the royals along with other wealthy families in large houses, decorated their homes using holly and ivy with a decoration known as a ‘Christmas Crown’ (resembling a wreath) which was constructed by weaving branches of hazel or ash together and then suspending them from high ceilings on Christmas Eve.

Throughout the Middle Ages, the kings that came and went celebrated their festivities at a range of different locations. For King Henry IV, most of his Christmas’s were spent at Eltham Palace in London.

In the Tudor period, Christmas in the royal household was dominated by entertainment and games, with Henry VIII enjoying dressing up in disguise, Robin Hood being a particular favourite.

A kitchen interior with a maid and a lady preparing game, attributed to Frans Hals in collaboration with another artist, circa 1600

A kitchen interior with a maid and a lady preparing game, attributed to Frans Hals in collaboration with another artist, circa 1600

During the reign of Elizabeth I, the Christmas tradition in the royal court called Misrule dominated proceedings. This was characterised by a period of ‘anarchy’, usually on Twelfth Night but sometimes marked on other occasions during the year. In that time, someone would be elected as ‘Lord of Misrule’ and manage the festivities which involved all sorts of chaos including major role-reversals in the palace.

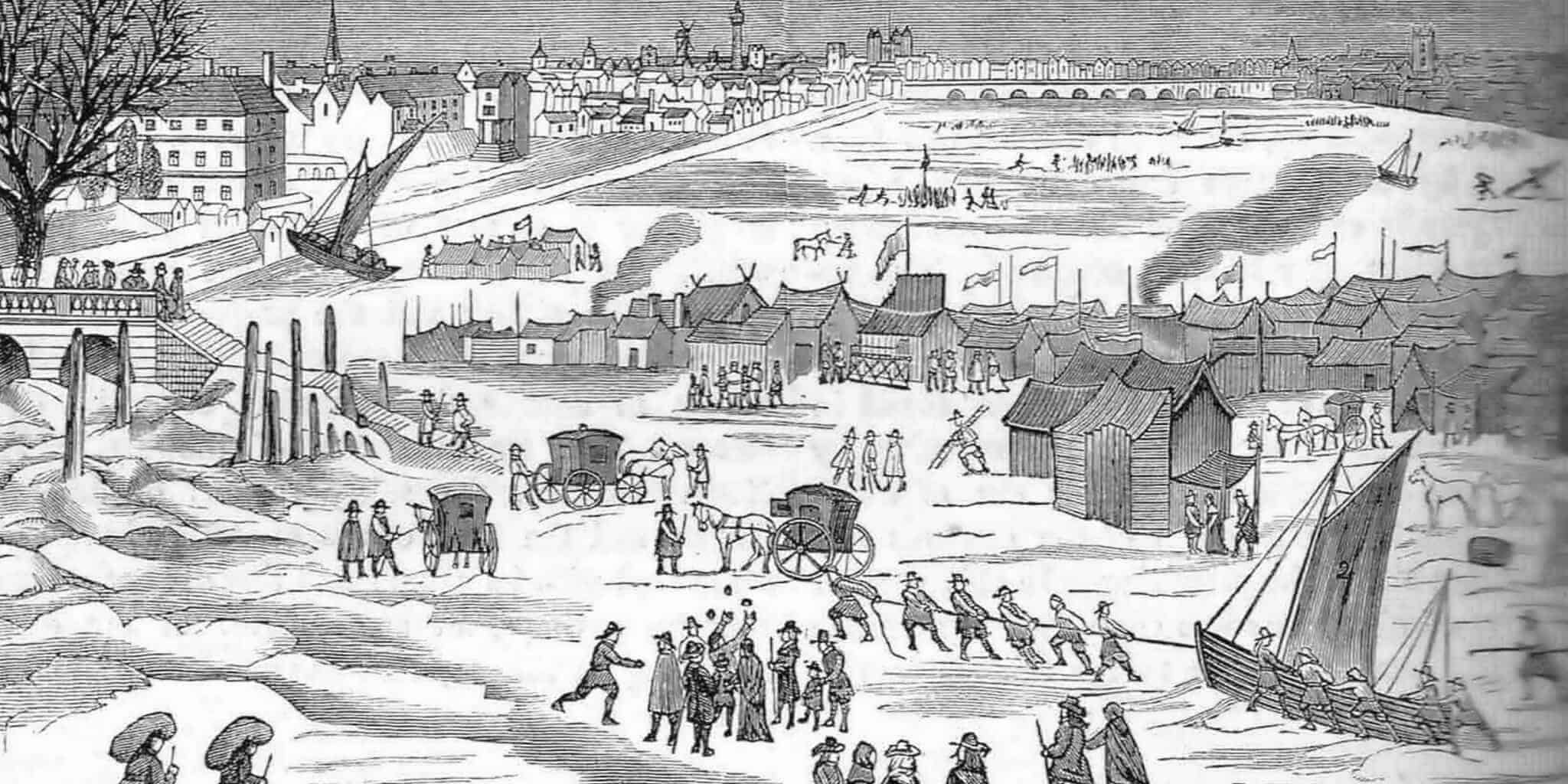

Whilst festive tradition both inside the palace and outside continued to grow and evolve, events in England took a calamitous turn when civil war broke out between the Royalists fighting for King Charles I versus the Parliamentarians.

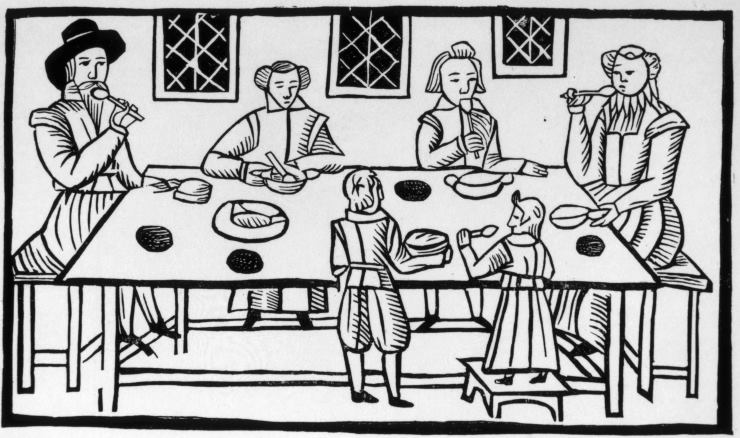

The banning of Christmas throughout England, Wales and Ireland had already begun in the mid-1640s with the Puritans who believed Christmas festivities were indicative of wastefulness. In 1642 Parliament made the last Wednesday of each month a ‘fasting day’ in order to reflect on their gluttony.

When King Charles and the Royalists found themselves facing defeat in 1646, the new rules that were implemented in this period included the abolition of all Christian festivities such as Easter, Whitsun, Pentecost and of course Christmas. Quiet contemplation rather than celebration was the order of the day.

The abolition of Christmas lasted until the restoration of the monarchy in 1660 which saw Charles II ascend the throne and reverse all legislation banning religious festivities. Christmas was officially back!

With the reinstatement of Christmas, new traditions and ways of celebrating began to evolve over the coming centuries, with the royal family very much at the centre of festivities. Some of the traditions which became ubiquitous included the Christmas Pudding, a typical British desert to be enjoyed after a hearty Christmas lunch. The first mention of which occurred back in 1714, when it was rumoured that King George I requested a plum pudding as part of the first Christmas feast of his reign, thus earning him the nickname ‘the Pudding King’.

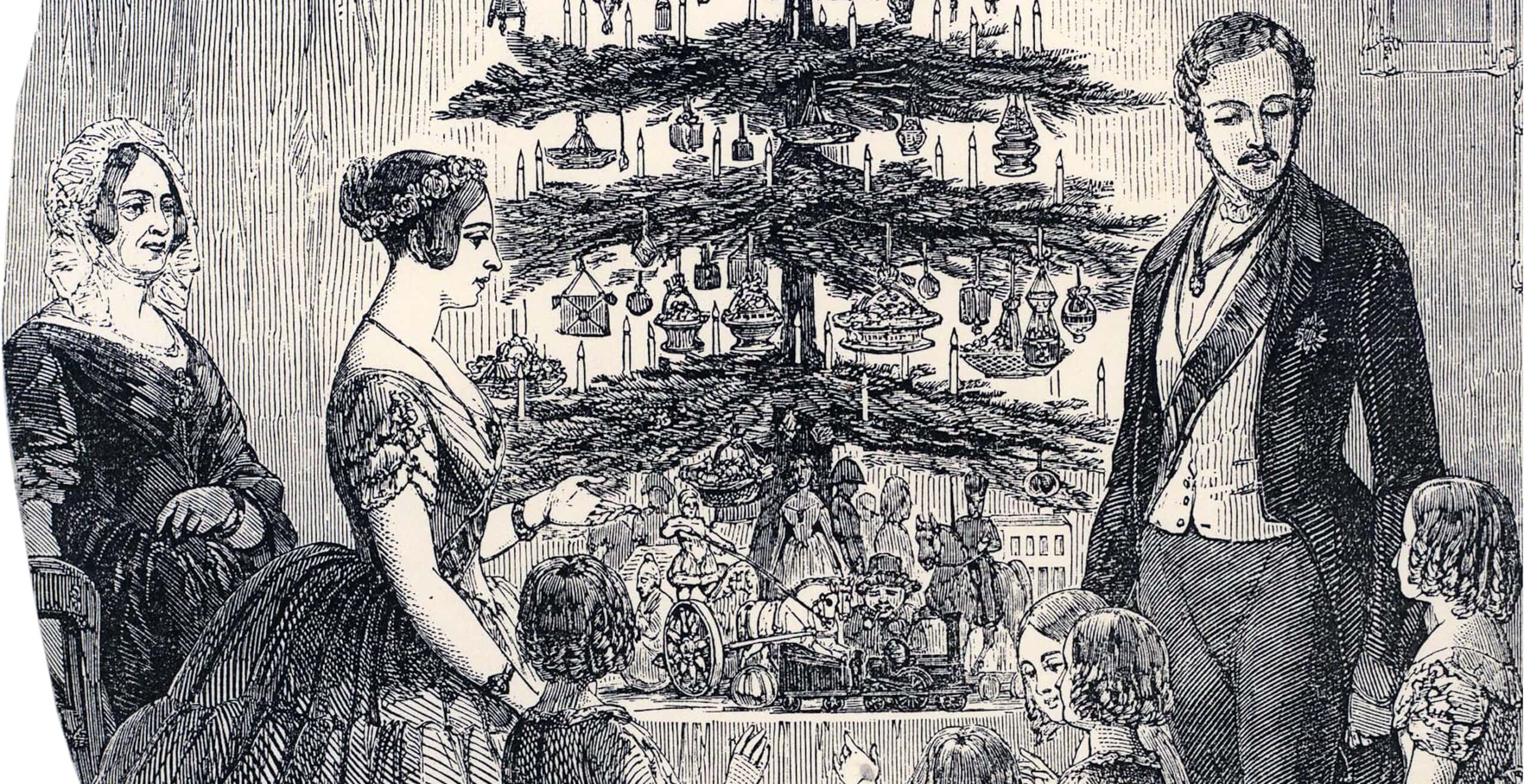

Arguably the monarch who proved most influential in establishing some of Britain’s most cherished traditions was Queen Victoria, thanks in large part to the influence of her German husband, Prince Albert.

Growing up in Kensington Palace, young Victoria enjoyed many happy festivities in her youth, describing in her childhood journal the decorations and ornaments which adorned the room.

Years later, after her marriage to Prince Albert, the royal household found itself embracing the now ubiquitous Christmas tree. Whilst it was first introduced by Queen Charlotte back in the eighteenth century, it was Prince Albert’s influence which saw the tree become the focal point of celebrations in the royal household.

Another Christmas tradition which gained much traction during the reign of Queen Victoria was the introduction of the Christmas card. With the production of Christmas cards rooted in the efforts of civil servant Henry Cole in 1843 who revolutionised the British postal system, by the 1840s, Queen Victoria began sending an ‘official’ Christmas card, a royal tradition which endures to this day.

In the following century, the Christmas period was punctuated by two world wars, however the public and the royal family continued to make an effort to mark the occasion. Ordinary people across Britain celebrated despite the hardships and distance between loved ones.

In 1914, the royal family were involved in sending all soldiers and sailors a Christmas card as well as the initiative known as the ‘Princess Mary Gift Box’ which was distributed to everyone on active military service.

Moreover, during the Second World War the two young princesses, Elizabeth and Margaret hosted pantomimes at Windsor Castle. These performances involved the local community and were used to raise money for the military.

One of the Christmas traditions for which the royals have become most well-known for is the Christmas Day speech.

On 25th December 1932, George V delivered his first Christmas broadcast, sending a message of goodwill which was heard by the British public on the day. Since then, subsequent monarchs have followed in his footsteps and sent out messages on the airwaves and subsequently on the television in 1957, with Queen Elizabeth appearing on the screen addressing the public from the comfort of their living rooms. For many families up and down the country and further afield in the Commonwealth, the Queen’s speech and now the King’s Speech, has become a significant part of the day’s festive schedule.

More recently, the image of the younger members of the royal family attending a morning service at St Mary Magdalene, Sandringham has become a common scene and one often attended by eager royal fans.

Today, the royal family opens its doors to the public during the festive season for visitors to enjoy the splendours of Windsor Castle and the Palace of Holyroodhouse in Edinburgh adorned in all its seasonal splendour.

Jessica Brain is a freelance writer specialising in history. Based in Kent and a lover of all things historical.

Published: 3rd December 2025