It was not until the mid-nineteenth century that feminism as an organised movement gained traction in Britain, launching the struggle for women’s suffrage and equality in the law, education, employment, and marriage. But a century before, a now largely forgotten group emerged who, in many respects, were forerunners of this more radical generation.

The eighteenth century was an age of elegance, etiquette and social order among the upper and aspirational middle classes. For a woman, her ‘place’ was to be fashionable, proficient in the social graces, and eloquent yet demure. Society did not deem it acceptable for a woman to be more educated than a man or to share her opinions. As the poet Anna Laetitia Barbauld put it, she should display only “a general tincture of knowledge as to make [her] agreeable to a man of sense.”

Typically, a young woman’s education might include reading, embroidery, music, dancing, drawing, a little history and geography, and perhaps some conversational French. For the few whose education went further, most deemed it prudent to keep their achievements to themselves lest it should ruin their chance in the all-important marriage market.

Dr John Gregory

In his book, ‘A Father’s Legacy to his Daughters’, published in 1774, the moralist Dr John Gregory wrote, “if you happen to have any learning, keep it a profound secret, especially from men, who look with a jealous and malignant eye on a woman of cultivated understanding.” But a few defied convention, openly flaunting their intellect and education. Some were married to sympathetic men, while others were scornful of a woman’s traditional role, rejecting any thought of a man having control over them.

One such woman was Elizabeth Robinson, born in 1718 into a wealthy, well-connected Yorkshire family. As a child, Elizabeth displayed an “uncommon sensibility and acuteness of understanding”, enjoying lively intellectual conversation with her parents and their close social circle. Years later, Samuel Johnson wrote of her, “She diffuses more knowledge than any woman I know, or indeed, almost any man. Conversing with her, you may find variety in one.”

As a young woman, Elizabeth was introduced to the enlightened Lady Margaret Harley, daughter of the 2nd Earl of Oxford, and the two became close friends. Through Margaret, three years her senior, she was introduced to many famous men of letters and was delighted to discover how men and women conversed as equals in Margaret’s household.

In 1734, Margaret married the 2nd Duke of Portland, but she and Elizabeth continued a regular correspondence. In a letter to Margaret in 1738, Elizabeth declared that she did not believe it was possible to love a man, professing no desire for marriage, which she saw as nothing more than an expedient convention. Nevertheless, in 1742, she married Edward Montagu, a grandson of the 1st Earl of Sandwich and a fabulously wealthy owner of estates and coal mines in Northumberland. Despite a 28-year age difference, their marriage proved mutually advantageous and cordial, if essentially loveless.

Elizabeth Montagu in 1762 by Allan Ramsay

From the early 1750s, Elizabeth Montagu began hosting intellectual gatherings – or salons – in her London home and later in Bath, depending upon the season. Soon, other wealthy, accomplished women such as Elizabeth Vesey and Frances Boscawen followed her lead. These salonnières invited both men and women, emphasising rational discussion and learning over sex. In addition, some of the great minds of the day were often invited as catalysts for debate. Among those known to have attended such events were Samuel Johnson, Edmund Burke, David Garrick and Horace Walpole. Usually, the only topic off limits was politics.

Soon dubbed the ‘Blue Stockings Society’ – and their participants ‘bluestockings’ – these salons were never a society in any formal sense. Instead, they were a loose social, artistic, and academic circle, united by the shared aims of improving opportunities for educated women to develop their knowledge and intellect and to earn a living in their own right. In his famous biography of Johnson, James Boswell records:

Such was the excellence of his conversation, that his absence was felt as so great a loss, that it used to be said, ‘We can do nothing without the blue stockings;’ and thus by degrees the title was established.”

In a salute to the movement, in 1778, the artist Richard Samuel painted ‘Characters of the Muses in the Temple of Apollo’, which featured the images of nine leading bluestockings and was afterwards dubbed ‘The Nine Living Muses of Great Britain’. Notably, the muses were all by then professionals in their respective fields. And with the exception of Elizabeth Montagu, by then rumoured to be the wealthiest woman in the country, they were also financially self-supporting.

‘Characters of the Muses in the Temple of Apollo’ by Richard Samuel (1778)

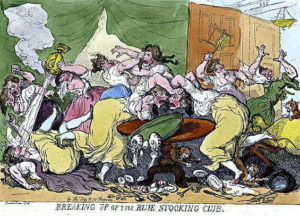

Whether Boswell’s account of the origin of the term bluestocking is correct remains a matter of debate. Whatever its source, bluestocking was initially considered a light-hearted jest, most women regarding it as a badge of honour. But as their gatherings grew more popular, a patriarchal backlash saw the expression become one of ridicule and shame. Lord Byron and Samuel Taylor Coleridge poured scorn on bluestockings, and William Hazlitt was typically blunt, “The bluestocking is the most odious character in society … she sinks where she is placed, like the yolk of an egg, to the bottom, and carries the filth with her.”

By the close of the eighteenth century, the bluestockings’ objectives were almost entirely frustrated; the label readily employed to attack women of intellectual confidence, acting as a deterrent to others.

Thomas Rowlandson’s caricature of a bluestocking salon descending into chaos in the absence of male guardianship

Bluestocking women also came to be viewed as elitist and politically and socially conservative, which largely explains the widespread exclusion of their writings from feminist history. More recently, however, it’s notable that scholars have begun rehabilitating them from this marginal position. Not all bluestocking women were aristocratic, socially prominent, or wealthy. Irrespective of their background, their common characteristic was a high level of intelligence and education, which meant they could hold their own and very often shine among some of the most intellectual men of the time. Their collective body of published work speaks for itself, encompassing areas as diverse as fiction, biography, history, science, literary criticism, philosophy, the classics, politics, and much more.

Richard Lowes is a Bath-based amateur historian who takes a keen interest in the lives of accomplished people who have passed under history’s radar

Published: 17th August 2022