Falling Like Statues

Falling Like Statues?

By Brian Penn, feature writer and popular arts critic.

The brutal murder of George Floyd in 2020 sparked a wave of protests across the globe. Britain’s monuments were the focal point as demonstrators de-faced the statue of Winston Churchill in Parliament Square; flags on the Cenotaph were also set ablaze in the ugliest spectacle. But it was the statue of slave trader Edward Coulston that drew the greatest ire. The statue had stood in Bristol since 1895, but was torn down and thrown into the harbour. Protesters roared with approval as it hit the water. Their actions were noble to many but really what did it prove? An empty gesture that has nothing to do with history and everything to do with criminal damage.

If only society’s ills could be cured so easily the landscape would be littered with empty plinths. The Coulston statue was retrieved and is now displayed in the M shed Museum. His deeds remain in the history books and the statue endures as a representation of his image; racism still blights our lives so has anything really changed?

The statue of Margaret Thatcher recently erected in her home town of Grantham has again questioned the effect on public order. It was originally intended for Parliament Square but authorities feared attacks by ultra-left wing groups. The statue was pelted with eggs the moment it was placed on its plinth. Local council leader Kelham Cooke said ‘we must never hide from our history’. Whilst the councillor’s comments are spot on statues seem largely counter-productive.

What really is the purpose of statues in an age dominated by powerful imagery accessible in a matter of key strokes? I have fostered a sense of ambivalence where such monuments are concerned. They are a cumbersome and cold method of marking someone’s existence. It only really makes sense when the subject pre-dates the photographic age. The statue of Richard the Lionheart outside Parliament is a case in point. He was King of England but died in 1199. Indeterminate portraits are the only source of information detailing his appearance. So a life size statue of Richard astride his horse is a welcome addition to the landscape.

Winston Churchill

Winston Churchill

However, in Parliament Square we have statues of Winston Churchill and Nelson Mandela. Two of history’s greatest figures are worthy of such tribute. But there are thousands of pictures and miles of film featuring both men. Is there any real need for these statues? Their juxtaposition will continue to be a source of friction; particularly as Churchill has been harshly judged without due recognition of his achievements. A crowd of statues jockey for prominence as the gothic splendour of Parliament stretches before them. Mahatma Ghandi and Abraham Lincoln are among a dozen icons representing liberty, progress and change. None led perfect lives, but all provide a soft target for anyone who wishes to score cheap political points.

Statues are too often seen as symbolic and many neglect the full history of individuals depicted. At Green Park the beautifully constructed memorial to Bomber Command was vandalised in 2019; it was the fourth attack on the monument in six years. Some will propagate images of the Dresden bombing without any context. Never mind 55,000 men who died fighting for the freedom we enjoy today. Never mind 55,000 men who had no choice in the targets they bombed. They were neither politicians nor activists, just ordinary men called into active service.

Is it acceptable to defile their memory because they served their country? Rules of play and codes of conduct are difficult to follow in times of war. Civilisation has broken down and decisions are taken in the knowledge that lives will be lost; nobody has totally clean hands. But yet again statues are vulnerable as the culprits fail to appreciate the whole story.

Joan Littlewood. Photograph taken by author.

Joan Littlewood. Photograph taken by author.

Other fields of endeavour are well represented but fail to arouse anything like the same reaction. Theatre Royal Stratford East owes much to legendary director Joan Littlewood who staged many of her early productions there. Yet her statue outside is barely noticed as patrons stroll past in blissful ignorance. The delightful statue of Charlie Chaplin in Leicester Square is buried in a sea of figures synonymous with the film world. It is the showbiz equivalent to Parliament Square with thirteen statues lurking on benches and walls. William Shakespeare, Gene Kelly and Bugs Bunny are among an eclectic mix; but I defy anyone to easily find them?

The world’s most popular sport has embraced the phenomenon with gusto. Virtually every football league ground has a statue positioned outside of a former player or manager. Wembley Stadium has a 10 foot statue of World Cup winning captain Bobby Moore looming large as fans alight from Wembley Park Station. It becomes a bold almost unnecessary statement. Aren’t his achievements in life sufficient memorial? A genuine sporting hero who glows in that stunning group picture after the World Cup Final in 1966.

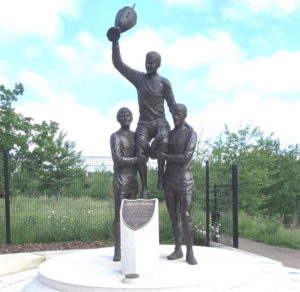

West Ham: Bobby Moore, Geoff Hurst and Martin Peters. Photograph taken by author.

West Ham: Bobby Moore, Geoff Hurst and Martin Peters. Photograph taken by author.

Moore’s former club West Ham have erected a statue of him alongside fellow World Cup heroes Martin Peters and Geoff Hurst. All played for West Ham in their European Cup Winners Cup triumph in 1965. People may pose for snaps alongside these heroes frozen in bronze, but wouldn’t a well-appointed museum fulfil the same purpose. A place where trophies, medals and artefacts can be viewed in the right context?

These icons of popular culture are captured but rarely acknowledged because they lack political significance. They fill an otherwise empty space in a quickly forgotten tribute.

But the finest statues adorn war memorials with a blank representation of a soldier at arms. They identify no one but everyone at the same time. Anonymous but no less explicit in its purpose; the everyman who made the ultimate sacrifice. It is a depiction of the human spirit; a troubled soul resting safe in the knowledge there is peace in the world they left behind.

They draw inspiration from the Tomb of the Unknown Warrior in Westminster Abbey. The body of an unknown combatant lies beneath a piece of Belgian marble to represent the fallen from the Great War and effectively all wars. The Unknown Warrior rests alongside Kings, Queens, scientists and writers; parity with the great and good is undoubtedly a fitting tribute.

War memorial. Photograph taken by author

War memorial. Photograph taken by author

My local war memorial is a masterstroke that represents the many and not the few. A lone soldier presenting arms is set astride a white stone column topped with a cross. The monument is surrounded by immaculately kept gardens. A flowerbed behind is traced in the shape of a cross that can be seen from ground level; a place of quiet and peaceful reflection. These are the statues that really matter, but as the Bomber Command monument proves even they are vulnerable to attack.

Perhaps the time has come to stop erecting statues that provoke such a violent reaction. They are now targets for those who wish to cancel the history they find offensive. But this defeats the object as history cannot be sanitised, censored or rectified. We should know our history whether it’s good, bad or indifferent; only then can we learn from experience.

Brian Penn is a feature writer and popular arts critic.

Published 17th August 2022