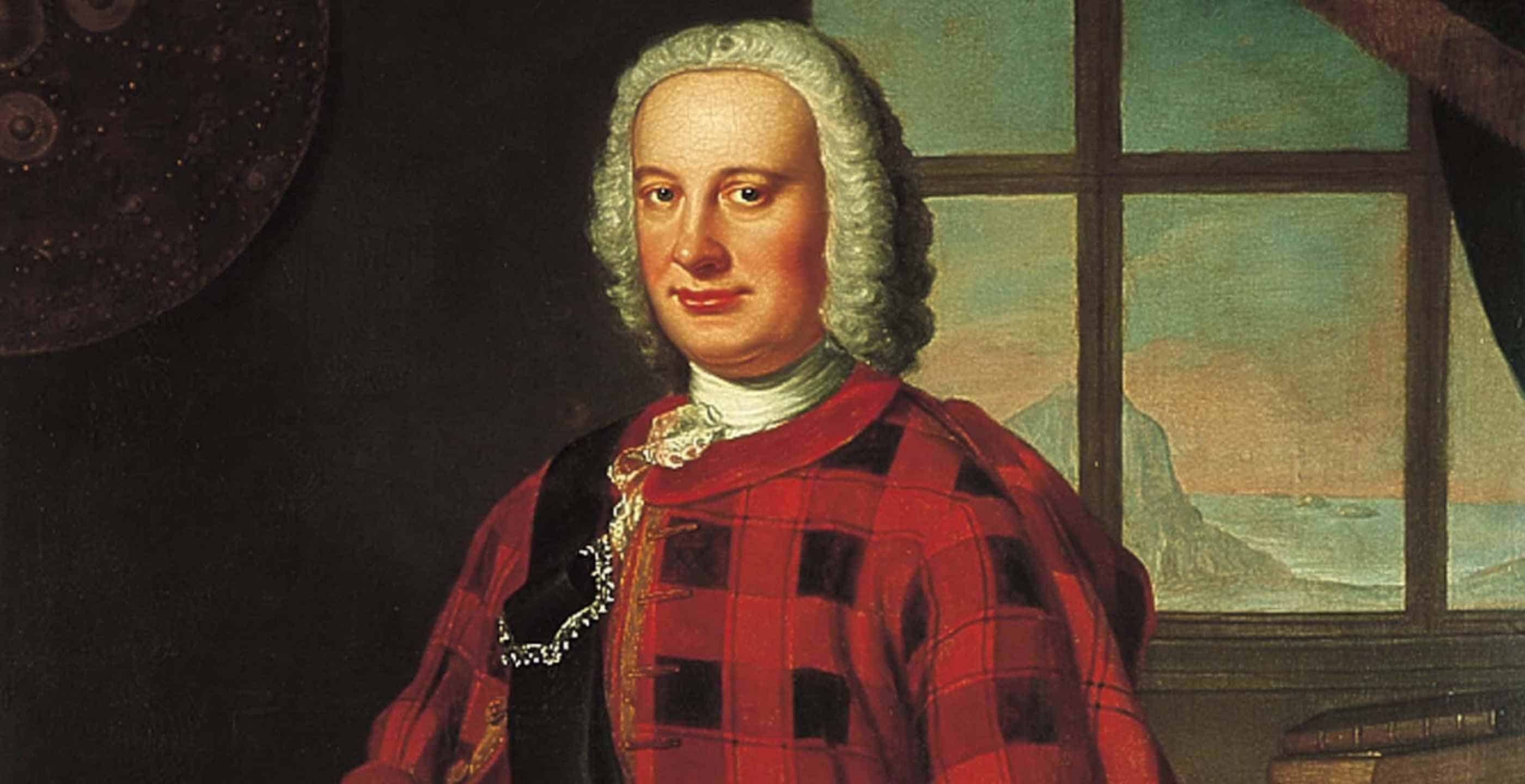

James IV (1473-1513) was Scotland’s Renaissance king. Potentially as influential and powerful as his neighbouring rulers Henry VII and Henry VIII of England, James IV was destined to die at the Battle of Branxton in Northumberland. This was also the famous, or infamous field of Flodden, a critical moment in the complex and combative relationship between England and Scotland in medieval and early modern times.

Many of Scotland’s young warriors fell alongside their king. The death of so many of Scotland’s youth at Flodden is commemorated in the Scottish lament “The Flo’ers o the Forest”. With them also died the dreams of James IV for a Renaissance court of arts and sciences in Scotland. At forty years of age, the king who had brought splendour and glory to his people and his country was dead, and an ignominious fate awaited his body.

James IV had been crowned king of Scotland at the age of just fifteen in 1488. His reign began after an act of rebellion against his father, the deeply unpopular James III. This was not unusual. James III himself had been seized by powerful nobles as part of a feud between the Kennedy and Boyd families, and his reign had been marked by dissension.

From the start, James IV showed that he intended to rule in different style from his father. James III’s approach to kingship had been a strange mixture of the grandiose and distant, with clear ambitions to present himself as some kind of emperor planning invasions of Brittany and parts of France. At the same time, he was apparently incapable of relating to his own subjects and had little contact with the more remote parts of his kingdom. This would prove disastrous, as in the absence of royal power, which was mainly focussed on Edinburgh, local magnates were able to develop their own power bases. His attempts to maintain peace with England were largely successful, but not popular in Scotland. The debasement and inflation of Scotland’s currency during James III’s reign was another cause for discord.

In contrast, James IV took action in practical and symbolic ways to show that he was a king for all of Scotland’s people. For one thing, he embarked on an epic horse ride during which he travelled in a single day from Sterling to Elgin via Perth and Aberdeen. After this, he caught a few hours’ sleep on “ane hard burd”, a hard board or tabletop, at the home of a cleric. The chronicler Bishop Leslie points out that he was able to do this because “the haill realme of Scotland wes in sic quietnes” (the realm of Scotland was so peaceful). For a country previously riven by conflict and dissension, whose inhabitants spoke Scots and Gaelic and had many varied cultural and economic traditions, this was a serious attempt to present himself as a monarch for all his people.

Horses and horsemanship would be important elements of James IV’s plans for Scotland, and Scotland was a country rich in horses. A visitor from Spain, Don Pedro de Ayala, noted in 1498 that the king had the potential to command 120,000 horse within just thirty days, and that “the soldiers from the islands are not counted in this number”. With so much territory to cover in his extensive kingdom, fast riding horses were essential.

It is perhaps not surprising that it was during James IV’s reign that horse racing became a popular activity on the sands at Leith and other locations. The Scottish writer David Lindsay satirised the Scottish court for wagering large sums of money on horses that would “wychtlie wallope ouer the sands” (swiftly gallop over the sands). The Scottish horses were famous for speed beyond Scotland, since references to them also occur in correspondence between Henry VIII and his representative at the Gonzaga court of Mantua, which was famous for its own racehorse breeding programme. This correspondence includes references to the cavalli corridori di Scotia (the running horses of Scotland) which Henry VIII enjoyed watching race. Later that century, Bishop Leslie confirmed that the horses of Galloway were the best of all in Scotland. They would later be major contributors to the speed of the Thoroughbred breed.

Indeed, Henry VIII might have found more than just the horses of his northern neighbour to be envious about. Bishop Leslie suggested that “the Scottish men at this time were not behind, but far above and beyond the Englishmen both in clothing, rich jewels, and heavy chains, and many ladies [had] their gowns partly set with goldsmith’s work, decorated with pearl and precious stones, with their gallant and well-accoutred horses, which were beautiful to view”.

As well as having their own fine, fast horses from Scotland, the court of James IV imported horses from various locations. Some were brought from Denmark to participate in the jousts that were popular events at Stirling, emphasising Scotland’s long-standing relationship with that country. James IV’s mother was Margaret of Denmark, and James VI/I would marry Anne of Denmark later in that century. James IV participated in jousts himself. His wedding in 1503 was celebrated at Holyrood by a major tournament. There were also imports of wild animals such as lions for the menagerie and probably for more cruel entertainments.

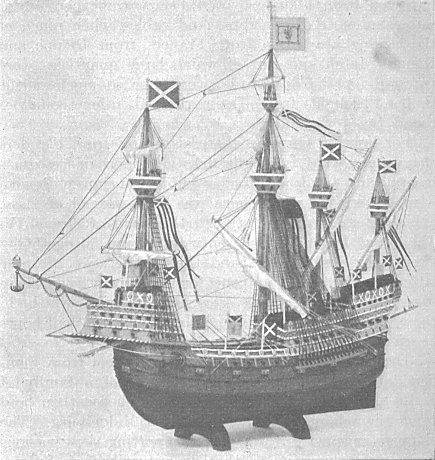

Shipbuilding was also a feature of his reign. The two most famous of his ships were the Margaret, named after his wife, the English Princess Margaret Tudor, and the Great Michael. The latter was one of the largest wooden ships ever built, and needed so much timber that once the local forests, mainly in Fife, had been ransacked, more was brought from Norway. It cost an eye-watering £30,000 and had six massive cannons plus 300 smaller guns.

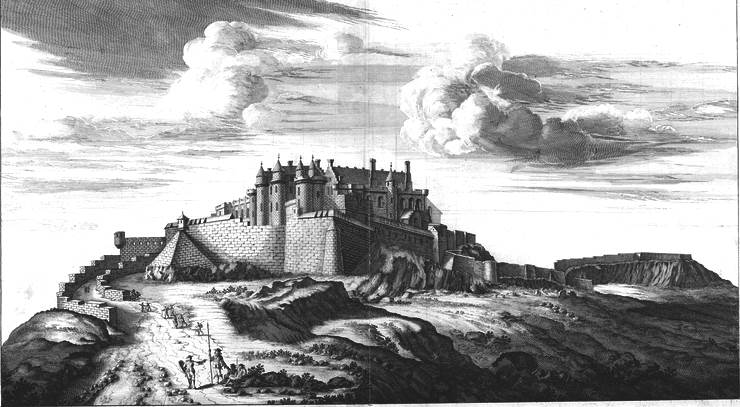

A magnificent ship, 40 feet high and 18 feet long, loaded with fish and bearing operative cannons, was floated on a tank of water in the beautiful hall at Stirling Castle to celebrate the christening of Henry, son of James and Margaret, in 1594.

Stirling Castle remains possibly James IV’s most outstanding achievement. This building, commenced by his father and continued by his son, still has the power to awe, although its frontage, known as the forework, is no longer complete. At Stirling, the king drew together a court of scholars, musicians, alchemists and entertainers from across Europe. The first references to Africans at the court of Scotland occur at this time, including musicians, and more ambivalently women whose status may be servants or enslaved people. An Italian alchemist, John Damian, attempted to fly from one tower using false wings, only to land in a midden (he was probably fortunate in having a soft landing!). The problem was, he realised, that he shouldn’t have made the wings using hens’ feathers; clearly these earthy rather than aerial birds were more fitted for the midden than the skies!

Literature, music, and the arts all flourished in the reign of James IV. Printing was established in Scotland at this time. He spoke several languages and was a sponsor of Gaelic harpists. That was not the end of James’s vision or ambition. He made many pilgrimages, particularly to Galloway, a place with a holy reputation to the Scots, and was given the title Protector and Defender of the Christian Faith by the Pope in 1507. He had extraordinary aims for his country, one of which was to lead a new European Crusade. Chroniclers of his reign have also noted his reputation as a womaniser. As well as long-standing mistresses, he also had briefer liaisons, which are noted in payments from the royal treasury to several individuals including one “Janet Bare-ars”!

The years of James IV’s reign that overlapped with those of Henry VII also encompassed the period in which royal pretender Perkin Warbeck, claiming right to the English throne as the alleged genuine son of Edward IV, was active. Warbeck’s insistence that he was the genuine Richard, Duke of York must have had some credibility, since his claim was accepted by several European royals. Prior to his marriage to Margaret, sister of Henry VIII, James IV had supported Warbeck’s claim and James and Warbeck invaded Northumberland in 1496. The subsequent marriage to Margaret, brokered by Henry VII, was intended to create a lasting peace between England and Scotland.

It was not, of course, to last. Skirmishing and unrest continued along the Anglo-Scottish border, and the policy of the new king Henry VIII – James IV’s brother-in-law – towards France precipitated conflict between the countries. Henry VIII, young, ambitious, and determined to both deal with any lingering Yorkist threats and put France in her place, represented a direct risk to Scotland’s long-standing relationship with France, the Auld Alliance. While Henry was engaging in warfare in France, James IV sent him an ultimatum – withdraw, or face a Scottish incursion into England, and a naval engagement off France.

The Scottish fleet set sail to support Norman and Breton forces, led by the Great Michael with the king himself on board for part of the journey. However, Scotland’s glorious flagship was doomed to run aground, an event which had immense psychological effect on the Scots. The Scottish army that entered Northumberland with the king at his head, was one of the greatest ever raised, including artillery and a force of perhaps 30,000 men or more. In what was to be the last successful attack by James IV, Norham Castle was burned. Henry VIII remained in France. The responding English forces were led by Thomas Howard, Earl of Surrey.

Before the Battle of Branxton, the irascible English king told James IV that “he [Henry] was the verie owner of Scotland” and that James only “held [it] of him by homage”. These were not words intended to promote any possibility of mending the relationship.

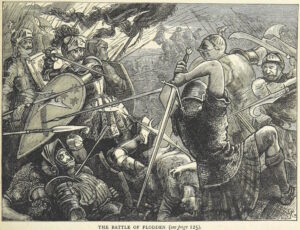

Despite the potential numerical advantage of the Scottish army, the location chosen by the Scots to adopt attacks by their close-formation pikemen was totally inadequate. Failed by the troops of Alexander Home, and perhaps by his own rashness and desire to be at the fore of his army himself, James IV led the charge against the English. In close fighting with the men of Surrey, during which the king nearly managed to engage with Surrey himself, James was shot in the mouth by an English arrow. 3 bishops, 15 Scottish lords and 11 earls also died in the battle. The Scottish dead numbered about 5,000, the English 1,500.

The body of James IV was then subject to ignominious treatment. The battle had continued after his death, and his corpse lay in a pile of others for a day before it was discovered. His body was taken to Branxton Church, revealing many wounds from arrows and slashes from billhooks. It was then taken to Berwick, disembowelled and embalmed. It then went on a curious journey, almost like a pilgrimage, but there was nothing holy about the progress. Surrey took the corpse to Newcastle, Durham and York, before it was taken to London in a lead coffin.

Katherine of Aragon received the surcoat of the King of Scots, still covered in blood, which she sent to Henry in France. For a brief time the corpse had respite at Sheen Monastery, but on the dissolution of the monasteries, it was shoved into a lumber room. As late as 1598, the chronicler John Stowe saw it there, and noted that workmen had subsequently sawed off the head of the corpse.

The “sweetly scented” head, still identifiable as James by its red hair and beard, resided with Elizabeth I’s glazier for a time. Then it was given to the sexton of Saint Michael’s Church, ironically given James’s association with the saint. The head was then thrown out with a lot of charnel bones and buried in a single mixed grave in the churchyard. What happened to the body is unknown.

The church was replaced by a new multi-story building in the 1960s, somewhat ironically again, since it was owned by Standard Life of Scotland, the assurance company. At the turn of the millennium, when it was announced this building too was likely to be demolished, there was talk of excavating the area in the hope of finding the head of the king. There appears to have been no action taken.

With the discovery of the remains of Richard III of England under a carpark a decade or so later, speculation turned to whether the head of poor James IV might one day be recovered. To date, there has been no such discovery. Today the site where the head of Scotland’s Renaissance king might lie is occupied by a pub known as the Red Herring.

Dr Miriam Bibby is a historian, Egyptologist and archaeologist with a special interest in equine history. Miriam has worked as a museum curator, university academic, editor and heritage management consultant.

Published 19th May 2023