Robert Watson-Watt was born on April 13th 1892 in Brechin, Angus. He was therefore, a contemporary of many other renowned Scottish scientists, engineers and inventors, those such as: Baron Kelvin, Alexander Fleming, John Logie Baird and Alexander Graham Bell. He was also a descendent of the celebrated engineer and inventor James Watt.

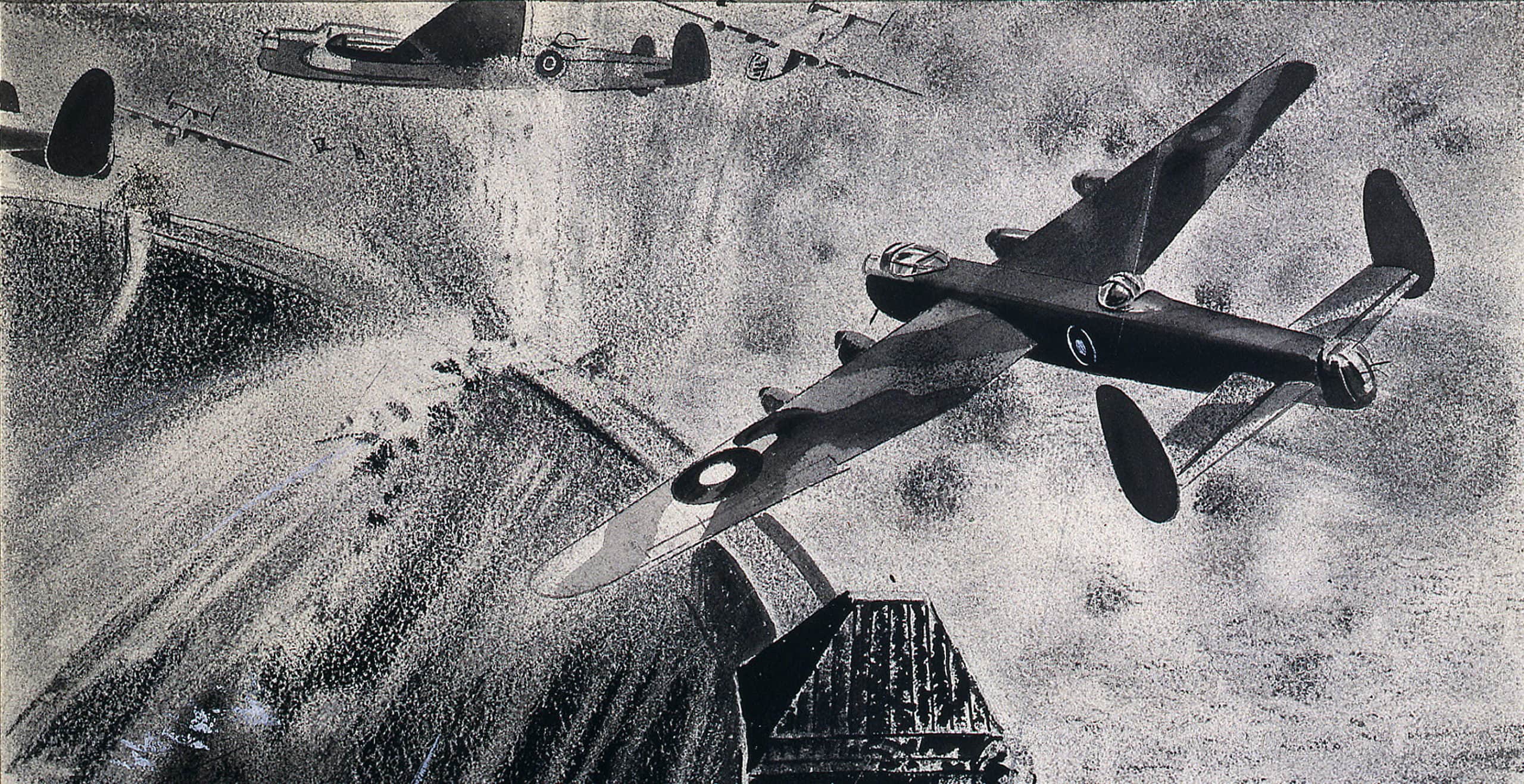

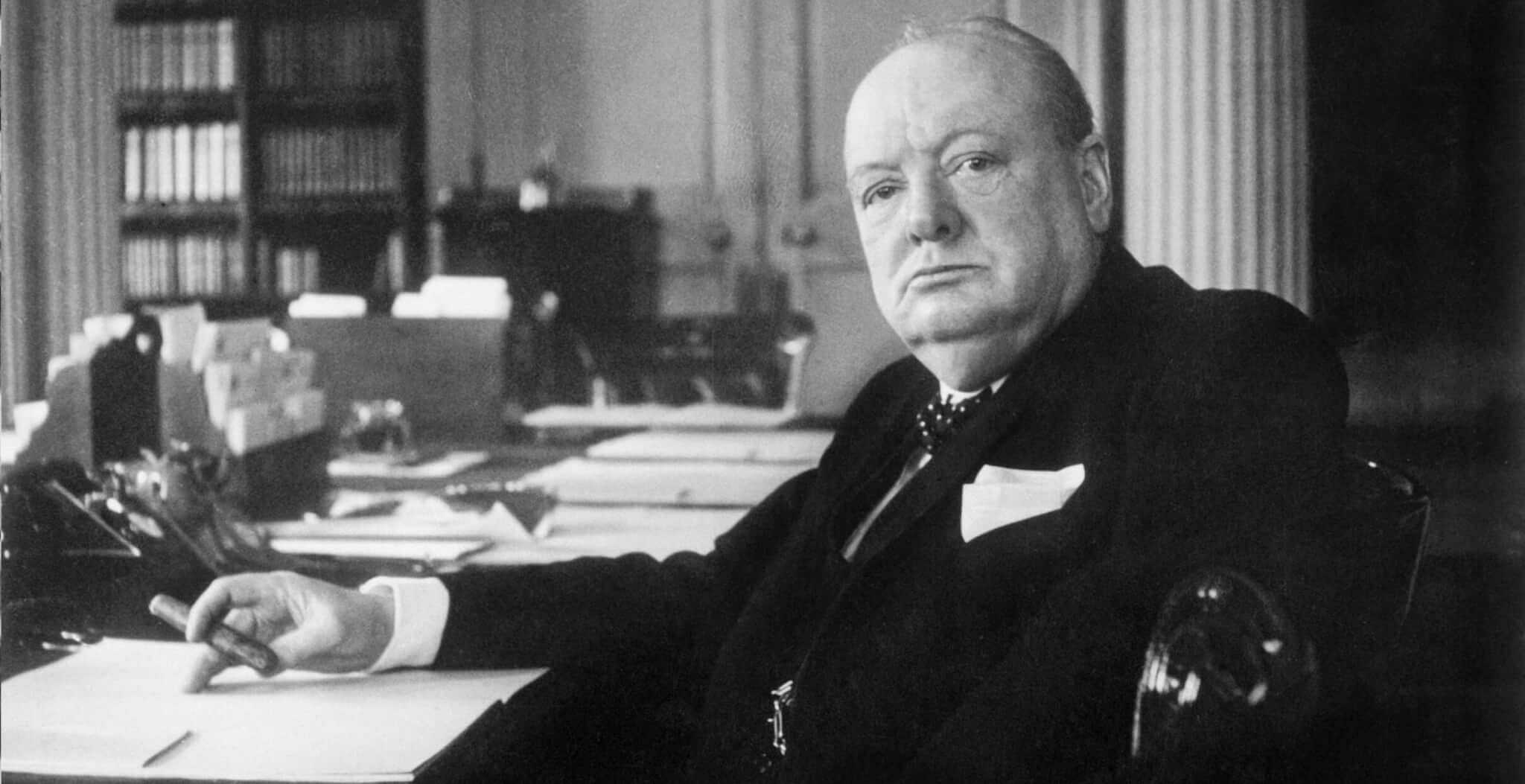

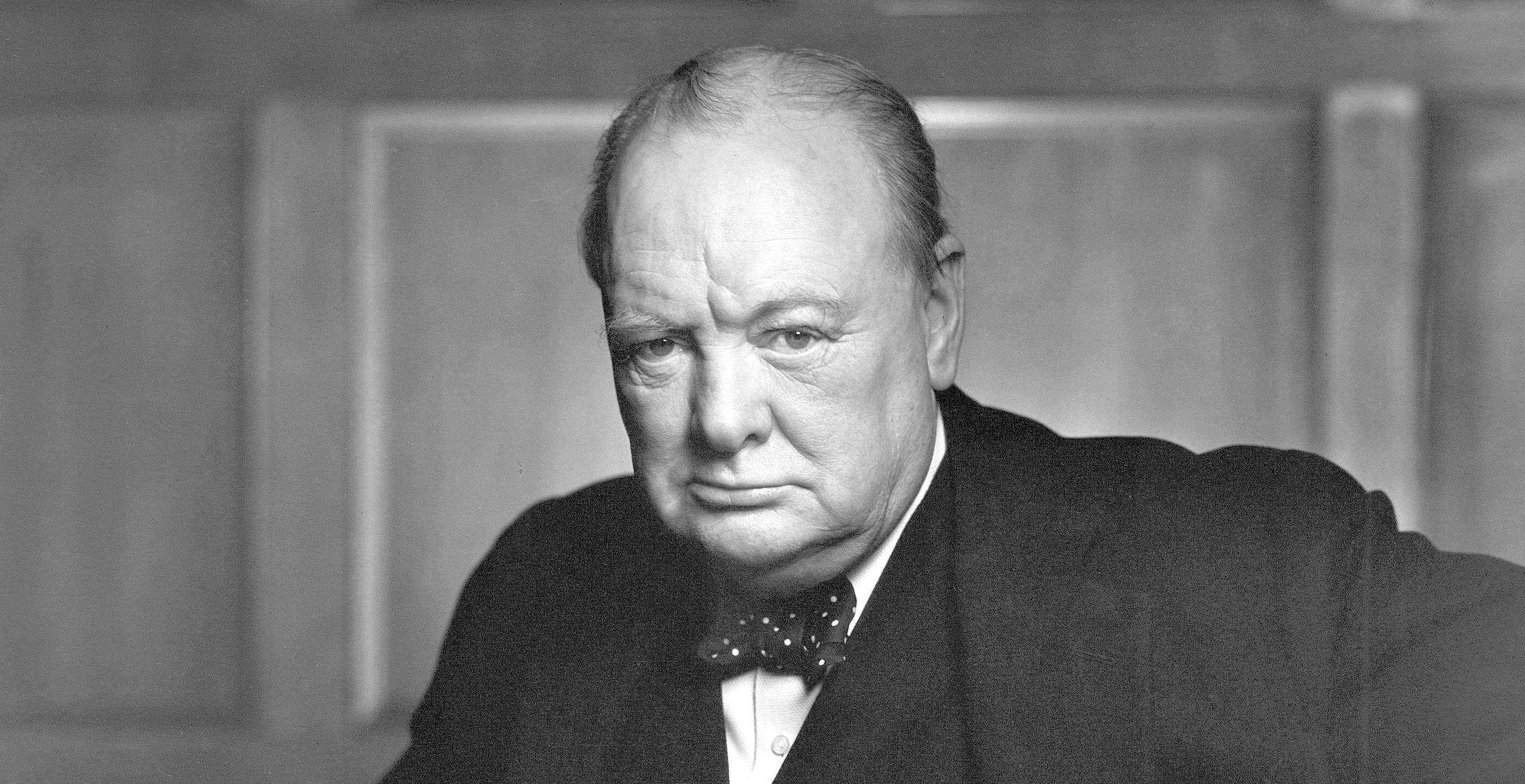

Robert Watson-Watt was a physicist who became known for developing radar in the 1930s and being indirectly influential in the success of the Royal Air Force in the Second World War. His inventions gave the RAF advanced warning of German aerial attacks. This was invaluable during the Battle of Britain in 1940, and many historians, and indeed contemporaries of Watson-Watt, including Winston Churchill, attributed Britain’s’ ability to fight off the German Luftwaffe as directly due to Watt’s radar systems. The Luftwaffe outnumbered the British aerial forces 3-1 at the time, but with Watt’s advanced warning system known as ‘Chain Home’, they were able to scramble in defence and intercept the enemy aircraft. Many also argue that it was Britain’s clear superiority in radar detection that contributed to Hitler’s decision to reconsider Operation Sealion.

Watt studied at University College Dundee, then part of St. Andrew’s University, gaining his BSc in engineering, and he went on to lecture there in later years. He began his professional career as a meteorologist at the Meteorological Office in 1915. There he would use his radar technology to detect thunderstorms and lightening. This was to help pilots in light aircraft avoid getting caught in the storms or being struck by lightning.

In 1924 Watt started work at a research centre in Slough and by 1934 he became head of the Radio Research Department. However, the next stage of Watt’s story could have been taken directly from a John Le Carré novel. He was approached by a representative from the Air Ministry of Britain and asked if he could create a ‘Death Ray’ using radio waves. A device that could, apparently, kill at long range and bring aircraft crashing down from the sky with a single pulse. The creation of a Death Ray had been (unsuccessfully) attempted by none other than Nikola Tesla, and Germany had falsely claimed to have already built one in 1933. However, at the time it was impossible and Watt rightly dismissed the idea as a fantasy. He did, however, begin to consider how to use radar technology to detect enemy aircraft at long range.

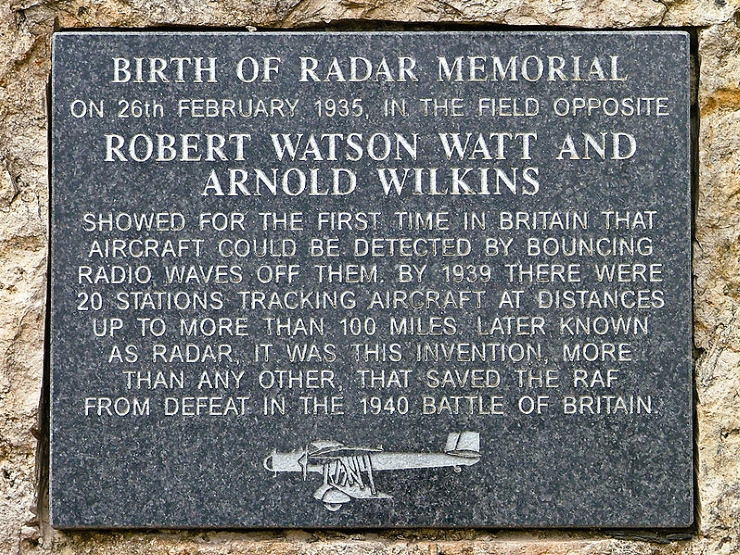

In 1935 he wrote a memo to the government about how radar could be effectively used to locate aircraft, and he even offered demonstrations. The first such demonstration was so secret, that only Watt, his colleague Arnold Wilkens who helped Watt throughout the entire development of the radar system, and one presentative from the air ministry witnessed it. The demonstration took place at Daventry and there remains a plaque there to this day.

The plaque reads –

“On 26th February 1935 in the field opposite, Roberts Watson Watt and Arnold Wilkins showed for the first time in Britain that aircraft could be detected by bouncing radio waves off them. By 1939 there were 20 stations tracking aircraft at distances up to 100 miles. Later known as radar, it was this invention, more than any other, that saved the RAF from defeat in the 1940 Battle of Britain’.

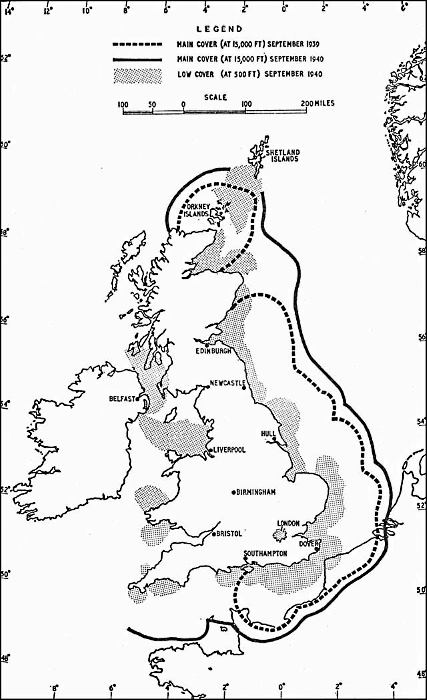

By 1935 his invention could detect aircraft as much as 140km away, which would give any defensive force a significant advantage. However, the system had to protect as much of the British coast as possible, and 140km was not going to be enough. So Watt came up with his ‘Chain Home’ system. This was a system that linked several radar towers along the coast that could relay information between them. In 1938 the first three Chain Home radars began twenty four hour duty, by 1939 there were 20 and by the end of the war there were 53.

Watt was soon asked to go to America to help the American forces after the devastating attack on Pearl Harbour in 1941. Then, throughout the 1950s and 1960s he lived in Canada, where he set up an engineering firm, and then America. It was in Canada in 1956 that Watt got a ‘taste of his own medicine’ when he was pulled-over by a police officer for speeding, due to the new application of his technology in radar guns. He was alleged to have said afterwards ‘My God, if I’d known what they were going to do with it, I’d have never have invented it!’ What he did do though, was to write a tongue-in-cheek poem about the experience.

Pity Sir Robert Watson-Watt,

strange target of this radar plot

And thus, with others I can mention,

the victim of his own invention.

His magical all-seeing eye

enabled cloud-bound planes to fly

but now by some ironic twist

it spots the speeding motorist

and bites, no doubt with legal wit,

the hand that once created it.

His developments in radar technology were, and indeed still are, used in: microwaves, air traffic control, and yes, radar guns for detecting the speeds of moving vehicles. In 1958 Watt published a book on his experiences with radar called, ‘Three Steps to Victory’. Watt returned to Scotland in the 1960s and in 1966 at the age of 72 he married his third wife Dame Katheryn Jane Trefusis Forbes; she was 67. They lived together in Pitlochry and when they died, Dame Katheryn in 1971 and later Sir Watson-Watt in 1973, they were buried together in Pitlochry.

Although he received the Order of the Thistle in 1942, up until 2014 the only monument to his and his team’s achievement was the small plaque in Daventry where the first air test had taken place. It was always thought by those who knew of his contributions during the war that more should have been done to honour him. Happily, this was achieved in 2014 when a statue was unveiled by the Princess Royal in Brechin, his home town. The statue shows Watt raising a spitfire in one hand, and holding a radar tower in another. Undoubtedly this is a fitting memorial to the man who contributed so much to the field of radar technology, and helped with the Battle of Britain.

By Terry MacEwen, Freelance Writer.

Published: 20th September 2022.