The Huguenots were French Protestants from the sixteenth and seventeenth century who fled from the French Catholic government fearing persecution and violence. As they fled, a diaspora of Huguenots travelled across the globe, settling and forming new communities in America, Africa and Europe.

The Huguenots were followers of the prominent theologian who became a leader of the Protestant Reformation, John Calvin. After a sustained period of violence and a clear impasse between Catholics and Protestants they fled in large numbers, hoping to establish a new life with religious freedom.

As well as establishing communities in Wales and Ireland, a large proportion of them settled in England where they were largely welcomed, as the British were not a Catholic nation and they were keen to welcome a skilled workforce.

As the Huguenot community settled into English life, the word ‘refugee’ entered the vernacular for the first time. It was to be the first use of the terminology to describe the population who had escaped from persecution in their country of origin and re-settled somewhere else in hope of a better and safer existence.

The Huguenot Cross

The story of the diaspora of French Huguenots traversing continents began in Europe, with the advent of great religious upheaval and change. The Protestant Reformation ushered in great cultural, political and social changes as well as the more obvious religious challenge to the established papal authority.

It was in this context, with a significant schism and rupture with the Christian faith, that the Huguenots emerged. Although no-one is certain as to the exact origins of the name, many believe the term to have originated from German or Flemish phrases describing the act of personal worship at home.

The Huguenot name was adopted around 1560 when the followers of John Calvin established the first French Protestant Huguenot church in a private property in Paris. The popularity of this religious movement grew exponentially, so much so that by 1562 there were around two million Huguenots in France alone with around 2000 churches.

In France, John Calvin proved to be a dominant figure leading the French Protestant cause. With natural leadership abilities he was committed to energising the movement through dogma and liturgy.

The theologian was a crucial figure in this development. Famous for his intellect, his approach was well-liked particularly by the more educated in French society. The main demographic of his followers included the elite of society including traders, military men and the higher echelons.

Above: Calvanist cross used by the Huguenots

In the context of a Catholic-dominated country, the initial flourishing of the religious movement did not appear to provoke the Catholic king into a response, partly because of the followers top ranking positions. However, in time, the royal toleration of the Huguenots would dwindle.

In January 1562 an important piece of legislation, the Edict of Saint-Germain, formally recognised the rights of the Huguenots to practice their religion as they saw fit. This notable act of toleration was carried out by the regent of France at the time, the widower of King Henri II, Catherine de’ Medici, who was attempting to shrewdly develop a middle-ground approach, pacifying the wishes of the Protestants whilst not threatening the status quo of the Catholics.

The Edict did however include the ban on Huguenots practicing their worship within the towns or at night, mainly to deter any religious fervour or political stirrings. Catherine had hoped that private worship would be enough.

Unfortunately, the edict itself was not easily passed through parliament and after a protracted series of events, it was processed. Sadly, the Massacre of Vassy had already taken place on the 1st March 1562 when 300 Huguenots who were holding a service outside of Vassy, were subsequently attacked by Francis, Duke of Guise and his troops.

In this bloody encounter, around 100 people were injured whilst 60 Huguenots were killed. With disagreement as to who was in the wrong, a long period of violence dominated the following decades, known as the Wars of Religion.

The French Wars of Religion lasted from its outbreak in 1562 until 1598, ensuring a great period of upheaval, large scale violence, death and disease. It is estimated around 3 million people died in this time.

After the Massacre at Vassy, sparks were flying all over and in April, the Huguenots seized the Hôtel de Ville in Toulouse. Unfortunately for them, they were faced with a mob of angry Catholics who fought back, resulting in heated street battles killing around 3000 people. Most of the victims were the Huguenots.

The battles would continue to rage on, with much of the fighting taking place in Rouen, Dreux and Orléans. This continuing violence only reached a temporary conclusion in February the following year when Francis, Duke of Guise was assassinated by the Huguenot Jean de Poltrot de Méré. The assassination led to uproar on both sides and eventually a truce was forced to bring about some kind of mediated peace, led by Catherine de’ Medici herself.

This resulted in the passing of the Edict of Amboise, also known as the Edict of Pacification. This treaty served to bring an end to the current stalemate of violence and restore the religious privileges of the Huguenots to some extent. Nevertheless, this was not about to bring an end to the conflict.

On the night of 23rd August 1572, the St Bartholomew’s Day Massacre ensued, bringing about the mass murder of around 70,000 Huguenots across France.

Instigated by Catherine de’ Medici, mother of King Charles IX, the orders were carried out, leaving the slaughter of Huguenot leaders and followers in its wake. Stirred by the attempted assassination of the Admiral Gaspard de Coligny, a military man and political leader of the Huguenots, the massacre ordered by the king lasted several weeks and took hold of cities, towns and villages across the country.

Murders, torture and mutilation carried out over a long period of time in twelve cities was the starting point of mass emigration from France of Huguenots desiring to live in more peaceful conditions.

In the first wave of Huguenots who fled, they travelled to England, Germany and the Netherlands, whilst any of those who remained were easily radicalised by the indiscriminate persecution executed by the Catholics.

Murder became commonplace and the bloodshed continued till the wars of religion reached their conclusion with the Edict of Nantes many years later in April 1598, finally giving in to Huguenot demands for equal rights.

In the following century, the religious division of France would end in more bloodshed when in 1685, Louis XIV enacted the Edit of Fontainbleau, making Protestantism illegal. At this point, with the prospect of facing further persecution, the remaining Huguenot community chose to leave France, choosing England as a main destination as well as Holland, Switzerland and further afield.

The mass migration of the Huguenots would end up having a massively detrimental impact on France with the mass exodus ensuring fewer workers, less wages, less trade and production. The Huguenots had been very prominent in the textile industries as well as being from the more educated classes; this was therefore a big loss to the French but a considerable gain for their new destination countries who would reap the benefits of a skilled labour force.

The migration of French Huguenots as well as Protestant Walloons was staggering and some of the largest England had witnessed. They would soon make up the largest ethnic minority in England.

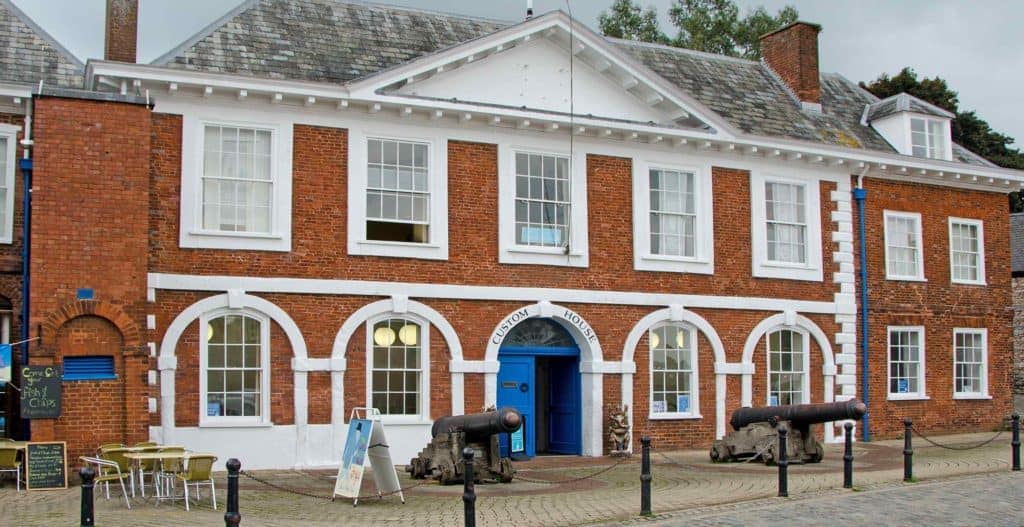

When they arrived, many of them in the ports of Kent, a large majority travelled to the cathedral city of Canterbury where Calvinism was well-established. It was here that they were granted asylum and were able to put down roots without the fear of persecution.

Kind Edward VI even went as far as to provide the western crypt of Canterbury Cathedral for their worship. Services would be held in French whilst the community settled into work as weavers, bringing with them new skills and techniques.

In Canterbury, a restaurant now occupies the site of the homes of Huguenot weavers which later became a weaving school. Their skills were necessary for their integration into English society and they soon practised a variety of professions.

Huguenot Weavers Homes in Canterbury

In Kent alone, they settled across the county, but particularly in the areas of Sandwich, Faversham and Maidstone, where refugee churches existed.

Meanwhile, in London, the first church of its kind, the French Protestant Church was created by a Royal Charter in 1550. With a large number of the refugees living in Shoreditch, they helped to create a valuable textile industry whilst in Wandsworth, they made a big impact on the horticulture.

In Norwich, East Anglia, textile skills, trade and production was boosted by the new wave of Huguenots who were the second refugees to join the community after earlier Walloon settlers. In Tours, the silk mill workers were predominantly Huguenot and their departure from the country was a great drain on the community.

Moreover, in the Midlands, glass making and perhaps even the famous lace industry would have been boosted by the new arrivals.

In total, around 200,000 Huguenots were believed to have left France with around 50,000 settling in England. This mass exodus resulted in one of the first refugee communities seeking a new life free from persecution, settling, working and living in Britain. Today, many people are aware of their Huguenot heritage, with famous figures such as Winston Churchill being a descendant of this persecuted community.

Today, there are living reminders of the Huguenots across England and further afield, a testament to the capacity of people to welcome, assimilate and prosper.

Jessica Brain is a freelance writer specialising in history. Based in Kent and a lover of all things historical.

Published: 10th September 2021