“Sir Edward Michelborne has taken and spoiled some of our friends there, whereby not only the utter overthrow of the whole trade is much endangered, but also the safety of our men and goods”.

These are the words of the East India Company who protested to the Lords of the Privy Council about the conduct of Sir Edward Michelborne and his activities in the East Indies. His desire for revenge had resulted in piracy and pillaging, thus endangering the reputation and commercial relationships which the East India Company had worked so hard to cultivate.

The story of Sir Michelborne’s unhappy relations with the EIC started some years earlier.

His own background was as a solider where he served as a captain in the Low Countries in 1591.

Edward also tried his hand at establishing a political career and became a representative of Bramber in parliament. Whilst based back in England, he began his association with the Earl of Essex.

He would subsequently serve with Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex, first as a commander aboard the Moon in 1597 as part of the Islands voyage (also known as the Essex-Raleigh Expedition) and subsequently in the unsuccessful campaign in Ireland in 1599.

Despite the campaign failing to crush the rebellion in Ireland, Devereux had seen fit to distribute a large number of knighthoods to his serving officers, including Michelborne.

After receiving his knighthood, Michelborne narrowly missed being implicated in the Essex Rebellion which involved Robert Devereux’s unsuccessful attempt at a revolt in 1601 against Queen Elizabeth and the faction supporting Sir Robert Cecil in the royal court.

Michelborne did not evade the authorities gaze however but managed to escape with a £200 fine, something which considering the popular punishments meted out during this era was a fortunate result.

Michelborne subsequently would turn his attentions to new projects and plans which would see him elevate his position and status.

At the time, the Age of Exploration was leading to several ships being commissioned for fact-finding voyages in search of new and exotic locations which would provide untold wealth in resources and commodities.

Michelborne appeared keen to get in on the action and petitioned the East India Company to gain command of the first venture heading to the East Indies.

As a chief player in court Michelborne received the recommendation from the Lord High Treasurer who instructed the London merchants who were planning the voyage to give him the role.

The merchants however had other ideas, especially after the disastrous experience of Edward Fenton and his expedition that saw him want to declare himself king of St Helena.

Instead, the merchants chose to turn Michelborne down citing their resolution “not to employ any gentleman in any place of charge” preferring instead to do “business with men of their own qualitye”.

James Lancaster was chosen instead to become the commander of the first voyage.

Such an obvious snub enraged Michelborne and his subsequent failure to pay the subscription amount which he had signed up to led to his name being removed from the Company’s roll.

Forced into the shadows whilst the EIC set about making arrangements for their upcoming voyage, Michelborne’s humiliation would fester for another four years before he retaliated with his own independent expedition to the East Indies which would prove to have a devastating effect on the company which had denied him his commercial ambitions.

Whilst Michelborne was forced to sit out of the first voyage to the East Indies, in the months and years that followed, a mixture of successes and failures continued to plague those ships which embarked on these difficult and sometimes fruitless expeditions.

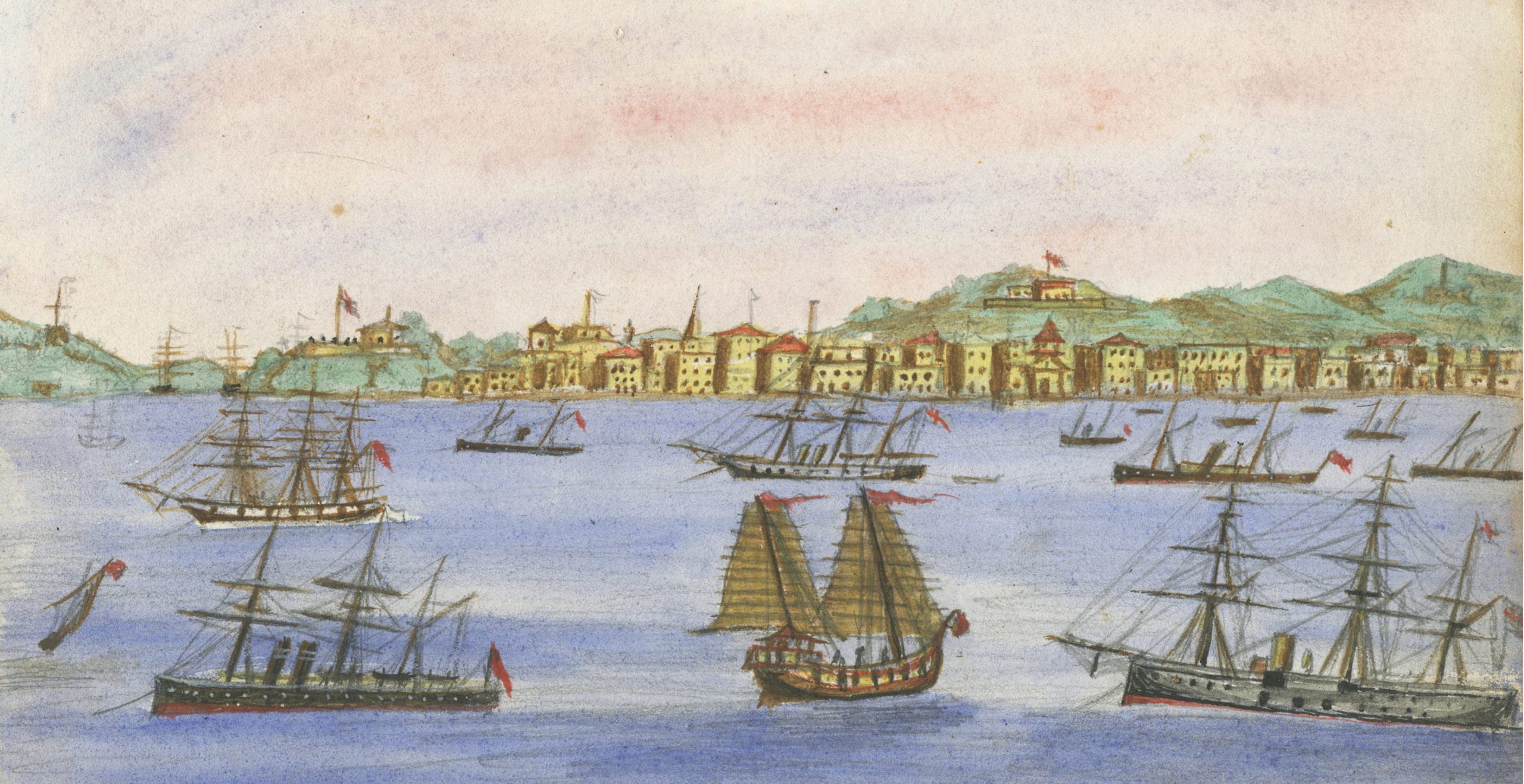

One of the main difficulties hampering English ambitions in the region, was the simple fact that it was not only the English who were vying for the sought-after commodities of the Spice Islands. In fact, the Portuguese and the Dutch had already made significant headway in the region and thus the diplomatic endeavours in Asia were not only about winning over the local leaders and natives, but rebuffing the claims and advances of their fellow European competitors. This rivalry became known as the Spice Race.

Meanwhile, with a new monarch on the throne, King James I was just as keen as his predecessor to keep up with England’s continental rivals. As a result, the lure of the spice markets combined with the failure of the EIC to make enough headway enticed the king to grant a license to none other than Sir Edward Michelborne.

After waiting to make his move, Michelborne had successfully petitioned the king and piqued his interest, resulting in him being awarded a licence to discover the Far East and to trade with the people he discovered in the region. Such an arrangement meant that Michelborne was in fact an interloper (sometime trading in breach of other monopolies).

Having secured the expedition, Michelborne and his crew set sail on the vessel known as the Tiger on 5th December 1604 from the Isle of Wight alongside one other ship.

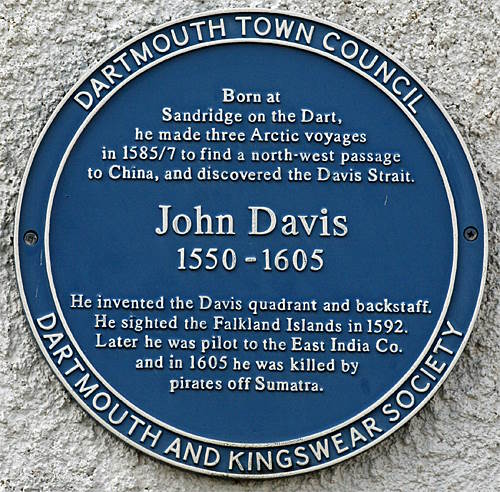

Aboard his vessel was well-known maritime figure John Davis, who was had previously accompanied Sir James Lancaster as Pilot-Major on the first voyage of the EIC, the expedition which Michelborne had failed to secure as his own.

Having fallen foul of Lancaster as a result of providing incorrect information about commodities and prices, Davis appeared happy to join Michelborne’s venture, in direct opposition to the monopoly held by the EIC in the region.

With two ships in tow, Michelborne’s voyage arrived at its destination, but no sooner had they reached the region did they embark on a pillaging and plundering exercise that bore no resemblance to their mission of making trade networks. Robbing was the name of the game and under Michelborne’s leadership, the vessels began attacking many of the ships they encountered.

Off the island of Bantam, ships were plundered and ransacked leaving a trail of destruction in their wake. One of those ships was an eighty ton Indian vessel which was subsequently fleeced.

In the harbour of Bantam, Michelborne took note of five large vessels, all of them Dutch and embarked on a display of blatant provocation where he threatened the captain of the ships and subsequently went up and down the harbour forcing the Dutch who were not keen to take up Michelborne’s offer of a challenge, to stay below deck.

His provocations would later have devastating effects on Anglo-Dutch relations in the region.

After successfully dominating the waters around Bantam, Michelborne’s arrogance and daring continued to go unchallenged however all this was about to end when he made a massive miscalculation that cost several lives.

Whilst navigating in the waters off the Malay Peninsula, a mysterious ship came into view and as a result, Michelborne despatched a boat on a reconnaissance mission. The men who were sent soon found out that this mystery ship belonged to the Japanese who appeared more than willing to invite them aboard.

The Japanese pirates had successfully plundered the Far East, taking ships off the coast of Borneo and having secured a huge booty were now making their journey back home to Japan.

Michelborne decided that having had such good fortune on his trip, that he would try his luck again. He subsequently sent another group of his crew to board the Japanese vessel in order to get an idea of what could be plundered.

Fully aware of the English intention, the experienced Japanese pirates showed themselves to be friendly and affable, willing to let the Englishman rummage around their ship and even pointing out some of their most valuable goods.

The English were perplexed by their good nature which caught them off guard, so much so, that when the Japanese asked for their actions to be reciprocated, the crew felt unable to refuse.

Michelborne subsequently welcomed the Japanese aboard, failing to ask them to disarm as they arrived. Instead, the Japanese were given the run of the ship and a jovial atmosphere soon enveloped the crews who began to mingle in what at first appeared to be a genial atmosphere. This however was all about to change.

In one moment the laughter and merriment gave way to sword waving and blood spilling on such a massive scale that the crew had never experienced in their lives. The Japanese who by now had the run of the ship went about slashing and hacking at their English counterparts, with one of the many casualties including John Davis who had run to the gun room but was hauled out and bled to death from his injuries.

Michelborne subsequently sprang into action, handing out pikes to the remainder of his men who managed to push back against the Japanese onslaught and kill some of their leaders.

Whilst the Japanese were well-armed with swords and knives the English still managed to fight back and the Japanese were driven towards the cabin. Unsure of what to do next, one of the English crew decided to use two canons to devastating effect. Firing at point blank range, the grim discovery of the mutilated Japanese crew was not for the faint-hearted.

Michelborne however was not finished, he then turned his attention to the Japanese vessel which was pummelled by canon fire until once again silence prevailed and one lone survivor was taken aboard the Tiger.

Such a devastating loss brought an untimely end to Michelborne’s escapades.

He returned to England in the summer of 1606 in disgrace alongside his surviving crew members.

Whilst Michelborne had discredited himself, the wider damage he had done to English ventures in the East Indies was immeasurable. So much so, that the EIC made complaints regarding his conduct to the Lords of the Privy Council who called for his goods to be seized.

With the reputation of English traders left in tatters, Edward Michelborne retired from public life, dying a few years later.

Michelborne had wanted to be a great and famous leader of a voyage, instead he became a sad reminder of the perils of greed and ambition, condemned to the footnotes of history.

Jessica Brain is a freelance writer specialising in history. Based in Kent and a lover of all things historical.

Published: 17th April 2024