Josiah Child’s War, perhaps better known as the First Anglo-Indian War, on the Indian subcontinent was fought between 1686 and 1690, resulting in a defeat for the English East India Company.

The origins of the conflict can be traced to the imperial and economic ambitions of the English East India Company (EIC) which had set its sights on controlling the profitable region of Bengal.

The area was described by the Emperor Aurangzeb as “Paradise of Nations” and was seen by others, such as Sir Josiah Child, Governor of the East India Company, as a location with much potential.

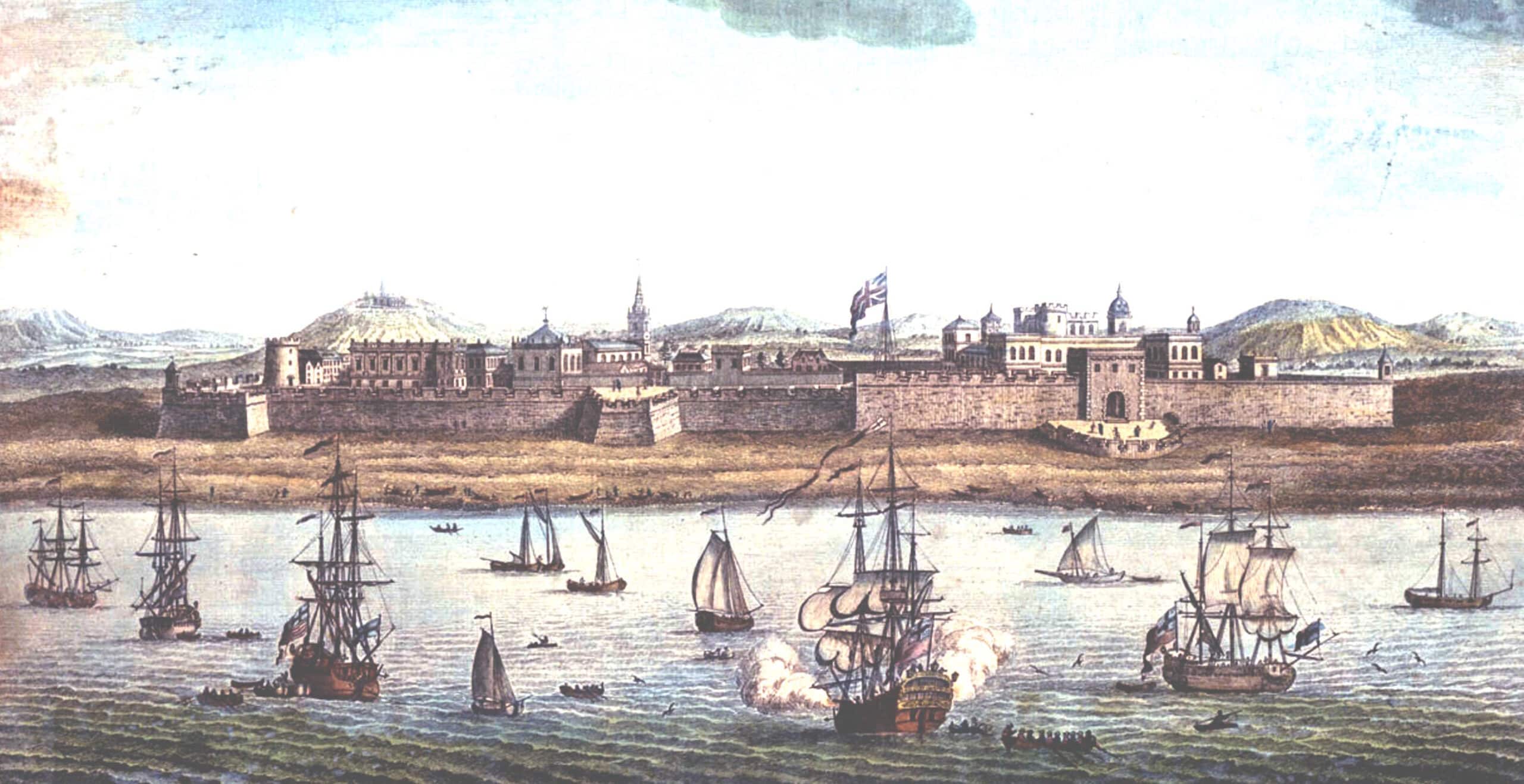

The Company had already established itself in Mughal India and taken monopoly over numerous fortified bases along the south eastern coastline, with the agreement of the local governors.

With the first factory set up in 1612, followed by a second base established in Madras in 1640 and a third in Bombay, imperial greed was motivating expansionist ideas across the entire Indian subcontinent.

One particular draw of the region was the abundance of the resource known as saltpetre, which at the time was highly sought after as the main component in gunpowder. The resources and land which the area could provide would prove to be a most enticing prospect.

Britain however was not without competition, as Portugal too had expressed interest in this commercially viable region. Bengal with its capital Dhaka, now modern-day Bangladesh, became a focal point of imperial interests from Europe and Britain was determined to gain a foothold.

In the early 1680s William Hedges, first governor of the EIC, was sent to approach Shaista Khan, the Mughal Governor of Bengal and uncle to Emperor Aurangzeb, in order to come to some arrangement.

The plan was for Britain to be able to negotiate its trading status in the area and the privileges it could expect in the Mughal provinces.

Such a meeting however did not go according to plan, as the Emperor took offence at Britain’s conduct and arrogance, breaking off negotiations leaving Hedges and the EIC without the security they needed to proceed with their economic plans.

The Governor of Bengal thus reacted by increasing the taxes for the EIC to pay, which Britain subsequently refused to comply with and instead responded with a show of military might.

The now Governor of EIC, Sir Josiah Child subsequently executed his plan to have the port of Chittagong seized and establish a base there, in order to cede some of the surrounding territory from the Mughal Empire.

With their eyes on the prize, the British enacted their plan with the support of King James II who gave permission for 12 warships to be sent with a crew of around 600 men and 200 cannons.

Leading this fleet was Admiral Nicholson. He and his men who were to be reinforced by another 400 men in Madras, who would assist in the armed invasion of the land surrounding the port.

Unfortunately for the crew, their plan was to be scarpered by a storm which meant that instead of arriving at Chittagong, they arrived at the Hooghly River.

This led Shaista Khan to instigate negotiations once more, however events on land soon brought an end to any possible discussions.

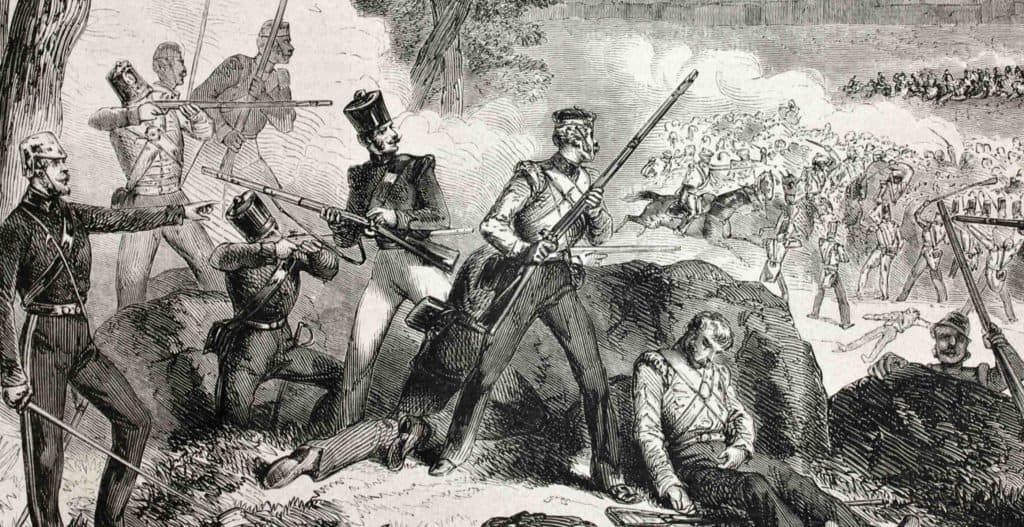

The event in question played out at a marketplace where three English soldiers, on shore leave, were strolling and encountered local Mughal officials. Soon the meeting resulted in a quarrel and ended with a severe beating at the hands of the local officers.

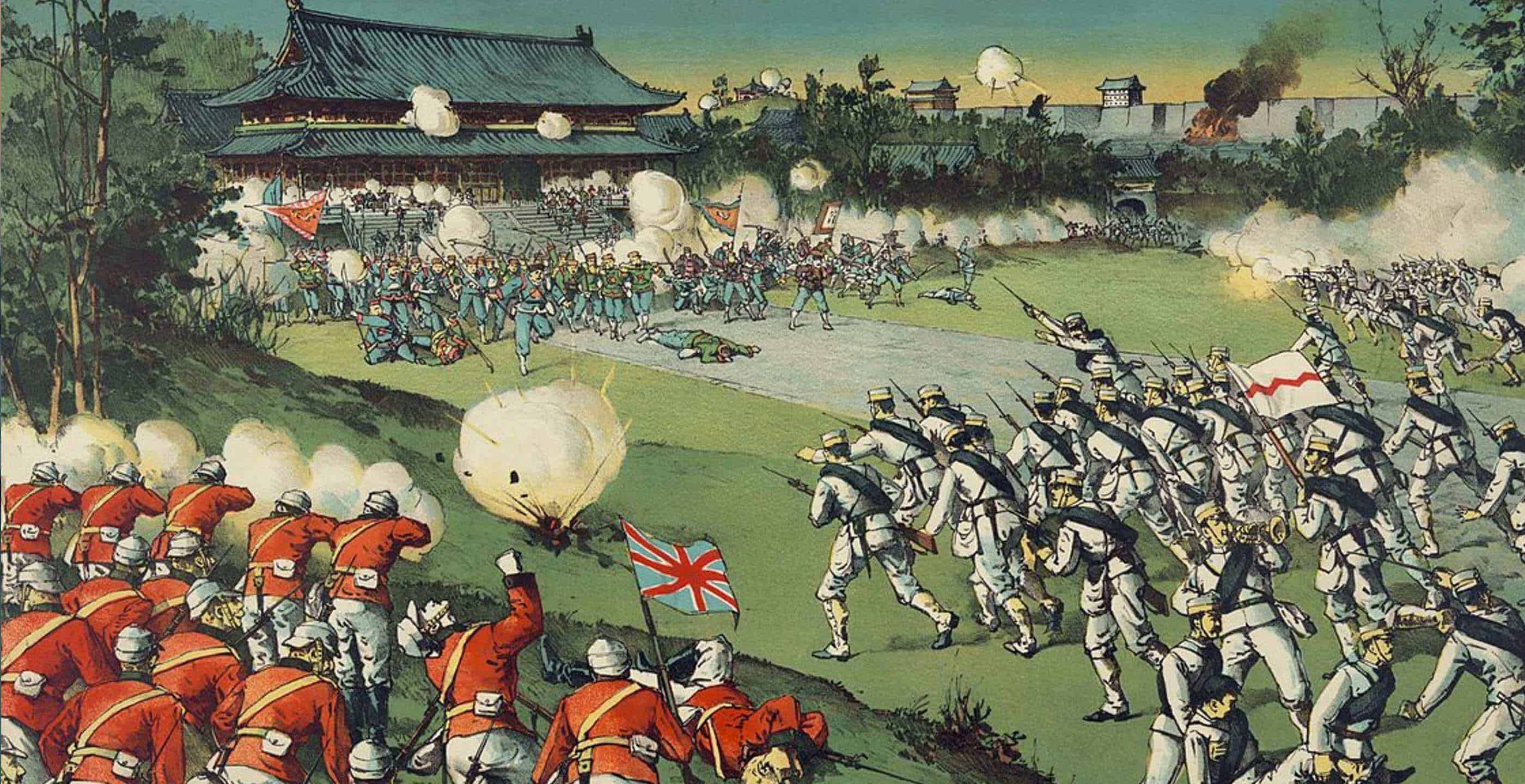

Upon finding out that some of his men were injured, Admiral Nicholson saw fit to dispatch a force to the town and begin firing on the local community.

Whilst talks to discuss the matter were initiated in Chuttanutty, the English were busy setting up a base at Ingelee Island under the command of Job Charnock. This would sadly prove to be a fatal error, as the position turned out to be unsuitable as the low swampland left the troops with no fresh water supply. Whilst the Mughals were busy attempting to assemble their troops, the English were left to die from fever and disease, leading to almost half of the men dying in the first three months.

With the standoff drawing to an end, the remaining English vessels sailed the west coast and were dispatched to blockade the Mughal harbours, encountering Mughal ships along the way.

Those caught up in these coastal skirmishes were innocent bystanders, including individuals on a pilgrimage to Mecca as well as ordinary merchants.

When news of their capture reached Emperor Aurangzeb, he felt it necessary to reopen discussions with the English.

Sadly, the EIC had other ideas, as reinforcements came in the form of Captain Heath who bombarded Balasore and then went on to Chittagong, where he had little success as the fortifications were well-defended, forcing the Captain and his men to return to base at Madras.

In response to the aggressive heavy-handed military actions at sea, Emperor Aurangzeb decided to retaliate in a way that would greatly affect the Company, inflicting heavy fiscal damage on the EIC.

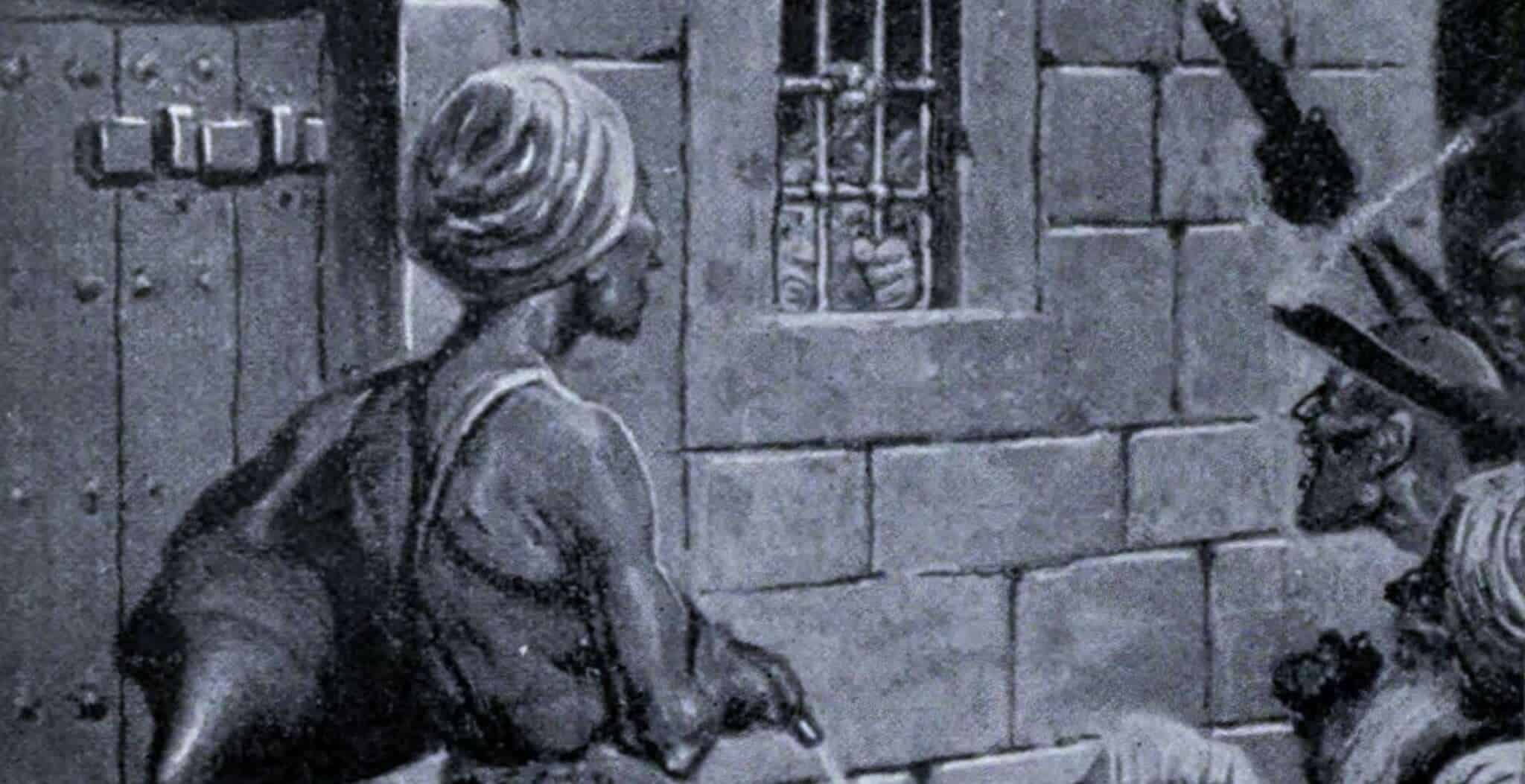

By ordering the confiscation of all English property including factories that were put under siege, the East India Company found all of its possessions on the subcontinent under threat.

With only the fortified towns of Madras and Bombay, the English were left with few options. Meanwhile, an impressive Mughal fleet under the command of Sidi Yaqub initiated a blockade on Fort William, the Company’s base in Bombay.

After a difficult and torturous resistance lasting almost a year, the fort eventually succumbed to the effects of famine and the English were left with little option but to concede defeat.

All that was left now was for the East India Company to send emissaries to launch their grovelling apologies and offer compensation in order to re-establish their economic foothold in the region, with the approval of the watchful Mughal Emperor of course.

After paying a fine of 1,50,000 rupees and giving their word that they would behave more appropriately in the future, the Emperor lifted the Siege of Bombay, bringing the First Anglo-Mughal war to a conclusion and forcing a great deal of re-strategizing and rethinking for the English.

This conflict, known by various names, has since fallen by the wayside in the history books, perhaps purposefully overlooked by the history writers of the time who were keen to obliterate the blot on the copybook of the otherwise impressive conquests in the English imperial record.

This war was however an important moment, as defeat was a vital step in Britain’s learning curve for securing power, money and its monopoly in regions it still knew very little about.

Jessica Brain is a freelance writer specialising in history. Based in Kent and a lover of all things historical.

Published: 20th April 2024