The UK now celebrates National Curry Week every October. Although curry is an Indian dish modified for British tastes, it’s so popular that it contributes more than £5bn to the British economy. Hence it was hardly surprising when in 2001, Britain’s foreign secretary Robin Cook referred to Chicken Tikka Masala as a “true British national dish”.

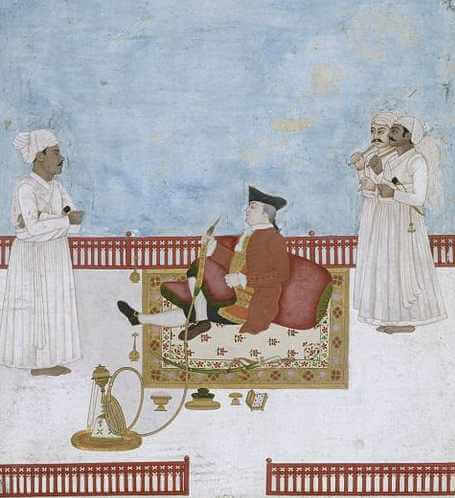

If Britain taught India how to play cricket, India perhaps returned the favour by teaching the British how to enjoy a hot Indian curry. By the 18th century, East India Company men (popularly called ‘nabobs’, an English corruption of the Indian word ‘nawab’ meaning governors or viceroys) returning home wanted to recreate a slice of their time spent in India. Those who couldn’t afford to bring back their Indian cooks satisfied their appetite at coffee houses. As early as 1733, curry was served in the Norris Street Coffee House in Haymarket. By 1784, curry and rice had become specialties in some popular restaurants in the area around London’s Piccadilly.

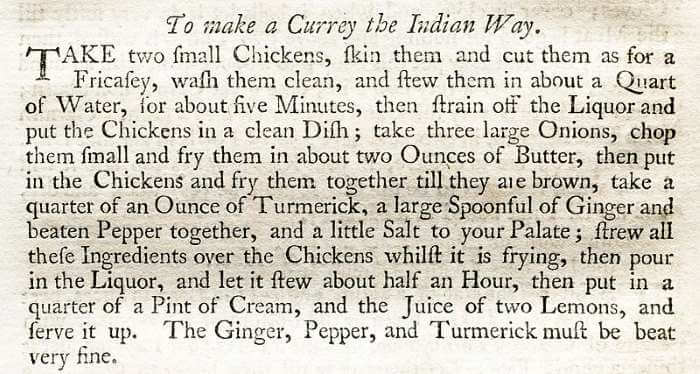

The first British cookery book containing an Indian recipe was ‘The Art of Cookery Made Plain & Easy’ by Hannah Glasse. The first edition, published in 1747, had three recipes of Indian pilau. Later editions included recipes for fowl or rabbit curry and Indian pickle.

One of the chief patrons of the restaurant was Charles Stuart, famously known as ‘Hindoo Stuart’ for his fascination with India and the Hindu culture. However, unfortunately, the venture was unsuccessful and within two years Dean Mohamed filed for bankruptcy. It was difficult to compete with other curry houses that were better established and were closer to London. Also, it is likely that nabobs in the Portman Square locality could afford to employ Indian cooks, hence not much need to go out to try Indian dishes.

Lizzie Collingham in her book ‘Curry: A Tale of Cooks & Conquerors’ argues that Britain’s love for curry was fuelled by the bland nature of British cookery. The hot Indian curry was a welcome change. In William Thackeray’s satirical novel ‘Vanity Fair’, the protagonist Rebecca’s (also known as Becky Sharp) response to cayenne pepper and chili shows how unfamiliar Britons were to spicy food:

“Give Miss Sharp some curry, my dear,” said Mr. Sedley, laughing. Rebecca had never tasted the dish before……..“Oh, excellent!” said Rebecca, who was suffering tortures with the cayenne pepper. “Try a chili with it, Miss Sharp,” said Joseph, really interested. “A chili,” said Rebecca, gasping. “Oh yes!” She thought a chili was something cool, as its name imported……. “How fresh and green they look,” she said, and put one into her mouth. It was hotter than the curry……….. “Water, for Heaven’s sake, water!” she cried.

By the 1840s sellers of Indian products were trying to persuade the British public with the dietary benefits of curry. According to them, curry aided digestion while stimulating the stomach thereby invigorating blood circulation resulting in a more vigorous mind. Curry also gained popularity as an excellent way of using up cold meat. In fact currying cold meat is the origin of jalfrezi, now a popular dish in Britain. Between 1820 and 1840, the import of turmeric, the primary ingredient in making curry, in Britain increased three fold.

However, the bloody revolt of 1857 changed the British attitude towards India. Englishmen were banned from wearing Indian clothes; recently educated public officials disparaged old company men who had gone native. Curry too ‘lost caste’ and became less popular in fashionable tables but was still served in army mess halls, clubs and in the homes of common civilians, mainly during lunch.

Curry needed a jolt and who better to promote it than the Queen herself. Queen Victoria was particularly fascinated by India. Her interest in India could be seen at the Osborne House, which she and her husband Prince Albert built between 1845 and 1851. Here she collected Indian furnishings, paintings, and objects in a specially designed wing. The Durbar Room (initially commissioned to be built as a sumptuous Indian dining room in 1890 by the Queen) was decorated with white and gold plasterwork in the shapes of flowers and peacocks.

Victoria employed Indian servants. One among them, a 24-year-old named Abdul Karim, known as the Munshi, became her ‘closest friend’. According to Victoria’s biographer A.N. Wilson, Karim impressed the monarch with chicken curry with dal and pilau. Later her grandson George V was said to have little interest in any food except curry and Bombay duck.

By the early 20th century, Britain had become home to around 70,000 South Asians, mainly servants, students and ex-seamen. A handful of Indian restaurants sprang up in London, the most famous being Salut-e-Hind in Holborn and the Shafi in Gerrard Street. In 1926, Veeraswamy opened at 99 Regent Street, the first high-end Indian restaurant in the capital. Its founder Edward Palmer belonged to the same Palmer family frequently mentioned in William Dalrymple’s famous book, ‘The White Mughals’. Edward’s great-grandfather William Palmer was a General in the East India Company and was married to Begum Fyze Baksh, a Mughal princess. Palmer’s restaurant was successful in capturing the ambience of the Raj; notable clients included the Prince of Wales (later Edward VIII), Winston Churchill and Charlie Chaplin, amongst others.

Curry was yet to establish itself firmly in British cuisine. In the 1940s and 1950s, most major Indian restaurants in London employed ex-seamen from Bangladesh, particularly from Syhlet. Many of these seamen aspired to open a restaurant of their own. After the Second World War, they bought bombed-out chippies and cafes selling curry and rice alongside fish, pies, and chips. They stayed open after 11 pm to catch the after-pub trade. Eating hot curry after a night out in the pub became a tradition. As customers became increasingly fond of curry, these restaurants discarded British dishes and turned into inexpensive Indian takeaways and eateries.

After 1971, there was an influx of Bangladeshi immigrants into Britain. Many entered the catering business. According to Peter Groves, co-founder of National Curry Week, “65%-75% of Indian restaurants” in the UK are owned by Bangladeshi immigrants.

Today there are more Indian restaurants in Greater London than in Delhi and Mumbai combined. As Robin Cook aptly puts it, this national popularity of curry is a “perfect illustration of the way Britain absorbs and adapts external influences”.

By Debabrata Mukherjee. I am an MBA graduate from the prestigious Indian Institute of Management (IIM), currently working as a consultant for Cognizant Business Consulting. Bored with mundane corporate life, I have resorted to my first love, History. Through my writing, I want to make history fun and enjoyable to others as well.

Published: November 2, 2017.