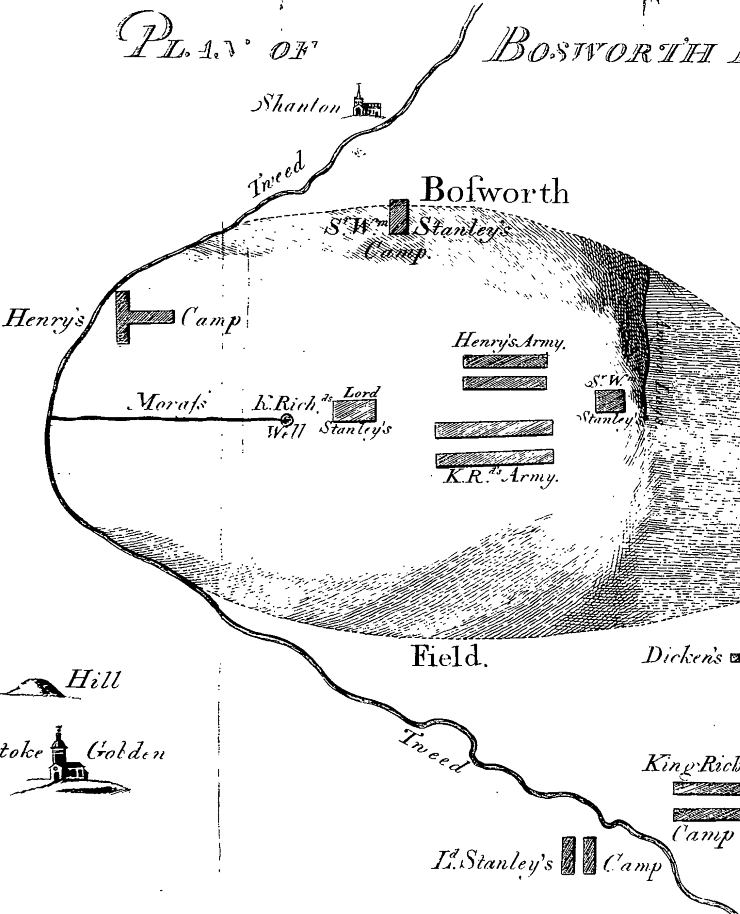

There are not many conflicts that can boast of three armies taking part in one battle. It is possible to have different armies fighting on the same side, for example during the D-Day Landings, when a force of Americans, British and Canadians attacked the German defences in Normandy. However, the Battle of Bosworth in 1485 during the War of the Roses (basically an English civil war) can claim this, with some historians saying that there were actually four different armed forces on the battlefield, with Richard III’s vanguard deciding not to engage his enemy and duly going home without raising a sword.

However, we shall examine this later on. The three main armies in 1485 were the king’s, Yorkist army in the region of 10,000-12,000; The rebel, Lancastrian army of approximately 5,000 men led by Henry Tudor and the third force of about 6,000 men led by the one-time Lancastrian, but more recently Yorkist noble, Lord Thomas Stanley.

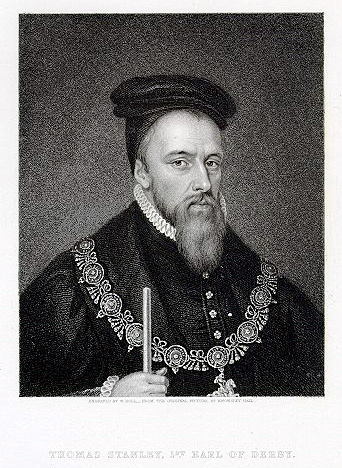

To understand why such a confusing situation was reached we need to consider the life and times of Lord Stanley, a magnate with extensive power and land in the northwest of England and North Wales. This scheming lord successfully manoeuvred his family between the warring factions with great skill and dexterity. Had he not, he and members of his clan would have perished in the thirty-year War of the Roses and at Bosworth field in August 1485.

It began in 1399, when the Stanleys supported the Lancastrian usurper, Henry Bolingbroke, to become Henry IV. However, by the time of Thomas Stanley becoming leader of the family sixty years later, they were teetering on the brink of a dilemma and not for the first time. In 1459 the Lancastrian queen, Margaret of Anjou, acting on behalf of her mentally unstable husband Henry VI, ordered Lord Thomas Stanley to attack his father-in-law, the Yorkist Earl of Salisbury. When the two main armies met at Blore Heath, Lord Stanley kept his contingent of 2,000 men a couple of miles away and out of the fray. A tactic he kept up his sleeve for future use!

By 1460 the new Yorkist king, Edward IV, rewarded Lord Stanley’s non-involvement at Blore Heath by endowing him with more land and power in the northwest of the country, as long as he remained loyal to him. This Stanley did for ten years until Edward IV fell out with Stanley’s brother-in-law, the ultimate noble, the Earl of Warwick, known as the ‘kingmaker’ due to his immense power. Stanley did not follow his in-law into the Lancastrian camp, but he ‘lent’ them his army for a period.

However after Edward IV’s restoration, Stanley was forgiven by the Yorkists for renting out his men to the opposition and he retained his power and land. He repaid this loyalty by partaking in an expedition into France in 1473 and played a major role in the capturing of the Scottish border town of Berwick-upon-Tweed under the command of Edward IV’s infamous brother, Richard, Duke of Gloucester, in 1475.

Whilst all this was going on Stanley became a widower and never a man to miss a chance of canoodling with the opposition, he married none other than Lady Margaret Beaufort, also widowed and more importantly mother of the main Lancastrian heir, Henry Tudor. This situation was tolerated by Edward IV as he believed Stanley was keeping her and her son under control on his behalf.

Things changed in 1483 with the sudden and unexpected demise of Edward IV. Again, Stanley was up to his old tricks. Outwardly he supported the young king’s (Edward V) uncle Richard, Duke of Gloucester, while arranging the marriage of his eldest son, George to Joan le Strange a leading member of the Woodville family and related to Edward V’s maternal family who happened to be the sworn enemies of Richard. Stanley’s luck ran true once more and though he was injured when Richard led a violent attack on the Woodville’s during a king’s council meeting leading to him being imprisoned in the Tower of London.

Stanley was not executed. Was it because he was too powerful, with plenty of sons to take revenge on the neurotic Richard of Gloucester during a vulnerable and important period in his life? While Lord Stanley was in the Tower, Richard usurped the throne from his young nephew and looked again to the northern noble to assist him. Lord Stanley was freed from his prison and appeared as strong as ever at Richard III’s coronation in 1483. He even carried the ‘great mace’ during the ceremony and his wife held the train of Richard’s queen.

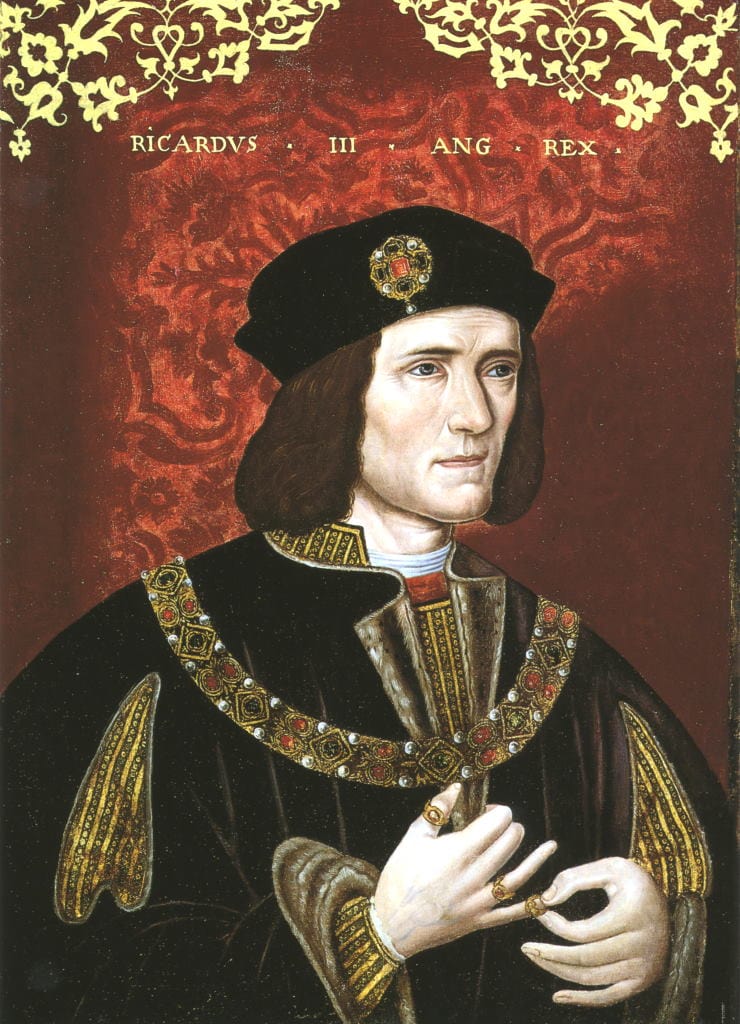

However, Stanley had difficulty manipulating Richard III to his advantage as he had done with other kings. Richard was shrewd and after an entire lifetime of fighting in the War of the Roses he was used to murdering his enemies. These included one of his own brothers and allegedly his own nephews, sons of his eldest brother, Edward IV. Like most great tyrants in history, such as Stalin in Russia and Nero in Rome, he was completely paranoid, not knowing whom to trust. This paranoia filtered down to all his nobles and when close friends began to rebel against him, he became psychotic and this would ultimately lead to his downfall. As for Stanley, Richard took all his wife’s lands from her as her son, Henry Tudor, became his main antagonist. In his totally deranged state, he gave all her lands to her husband Stanley, hoping upon hope that he would keep her under control and remain loyal to his Yorkist cause.

In 1485 Stanley realised that things were coming to ahead. From his wife he learned that his stepson, in exile in France, was about to invade. He therefore asked Richard for permission to return to his lands in the northwest of England and, ‘consolidate his power there’. Richard proved to be no mug and agreed, as long as Stanley left his son George as his replacement at his court. In 1485 with Henry Tudor’s invasion in Wales, Richard demanded Lord Stanley and his brother, Sir William Stanley, attack the Tudor rebel. When Lord Stanley replied that he could not do so because he had the ‘sweating sickness’, man-flu to you and me, Richard knew he could not trust the Stanleys. He marched north to meet Henry Tudor with George Stanley as his hostage hoping this would ‘help’ the Stanleys come to their senses and persuade them to join him, or at least stop Stanley from fighting alongside his stepson, Henry Tudor.

Just in case Lord Stanley had forgotten who was being held prisoner in the Yorkist camp, Richard sent a messenger to the Stanley’s HQ, on the night before the battle, notifying the lord that his son George would be executed during the battle if he did not aide him. Stanley sent Richard’s messenger back with the frank and glib response, ‘Sire, I have other sons’.

Therefore, on the morning of 22nd August 1485 on a field outside Market Bosworth we have three armies, with Stanley’s force holding the balance. Should he fight for his Lancastrian stepson, Henry Tudor, or save his eldest son’s life and assist the Yorkist king, Richard III? As at Blore Heath he sat on a hill watching the battle like a mob leader engrossed in a punch up between rival gangs.

When the schizophrenic Richard saw his chance to eliminate the rebel Henry Tudor, by charging at him with his cavalry, Lord Stanley made his move. With Richard unable to give the order to kill George Stanley as it looked as if he was about to murder Henry Tudor in the middle of the battle, Stanley gave the order for his men to charge down the hill and attack the king and his royal retinue. The Stanleys arrived in the nick of time with Richard a sword’s length away from Henry and it was Stanley’s men who unseated Richard from his horse and hacked him to death.

Before his demise Richard had ordered in his reserves, in the shape of Henry Percy (Earl of Northumberland) and his force to come to his rescue. It was a sizeable detachment and to some historians the ‘fourth army’ that was mentioned earlier. However, for reasons known only to himself, Northumberland literally turned his back on his king, leaving him to his fate and led his army away from the battle. He was to pay for this four years later when a Yorkist rebellion in the North of England found him, condemned him as a ‘rank traitor’ and executed him.

For his loyalty to his stepson, Lord Thomas Stanley was rewarded handsomely and this we would think would be the end to the story, but not so! It appears the Stanleys could not stop dabbling in Tudor politics and Thomas’s brother Sir William Stanley changed sides again and supported the Yorkist rebel, Perkin Warbeck. Unlike previous kings Henry Tudor, now Henry VII, did not see any threat from the Stanleys, as he had now firmly secured his throne and Sir William was executed in 1495. This marked the end of Lord Stanley’s influence in England’s affairs as he felt too weak to even reprimand his stepson for murdering his younger brother.

And so finally ends the story of an English noble who successfully negotiated his way through the turbulent waters of the War of the Roses and inadvertently helped set up the Tudor dynasty. A royal family who would produce our modern parliament, start the British empire in North America, support the arts, especially William Shakespeare and set the foundations of the protestant Church of England which is still the most popular religion in the country today. Where would modern England and for that matter, Britain be without the skillful and cunning manoeuvres of Lord Thomas Stanley?

By Graham Hughes, history graduate (BA) from St David’s University, Lampeter and presently head of history at Danes Hill Preparatory School, a leading British prep school.