Described by James I as ‘a fair woman with a black soul’, Lady Penelope Devereux was a prominent figure in the courts of Queen Elizabeth I and King James I. A famous beauty with golden hair and dark eyes, she was well educated, an excellent dancer and fluent in Italian, French and Spanish. She was also involved in religious and political intrigue.

Penelope’s lineage was impressive: descended from England’s medieval kings and the daughter of the Earl of Essex, Penelope‘s great-grandmother was Queen Elizabeth I’s aunt, Mary Boleyn. Born at Chartley Castle in Staffordshire, she was the daughter of Walter Devereux, 1st Earl of Essex and Lettice Knollys.

After the death of her father Essex in Ireland during a disastrous military campaign in 1576, Penelope became the ward of the Earl and Countess of Huntingdon. Hers was a strict Puritan upbringing and life was quite simple until she was presented at Court in early 1581.

That same year she married Robert, 3rd Baron Rich (later 1st Earl of Warwick), a strict Puritan. She would go on to bear him at least four children.

Her widowed mother Lettice was out of favour for marrying Queen Elizabeth’s favourite the Earl of Leicester, without approval and in secret. However this did not seem to affect Penelope’s life at court: indeed she became a popular figure, especially as her brother Robert’s influence grew with the Queen.

On the death of her father, her brother Robert had inherited the title Earl of Essex. In October 1589 Essex, Penelope and Lord Rich entered into a secret, dangerous and treasonous correspondence with James VI of Scotland, the likely successor to the throne on the death of Elizabeth, promising their support for his accession. James was cautious in his response; he was unwilling to put his succession to the throne at risk by being implicated in planning to usurp Elizabeth.

At this time Penelope was also beginning to doubt her Puritan upbringing and flirting with the idea of converting to Catholicism, which in Elizabeth’s Protestant England was a very dangerous thing to do. It was also a capital offense to harbour a Jesuit priest: however this did not prevent Penelope from giving sanctuary to Father John Gerard, one of the leaders of the Catholic mission in England, in her house at Leez in 1594.

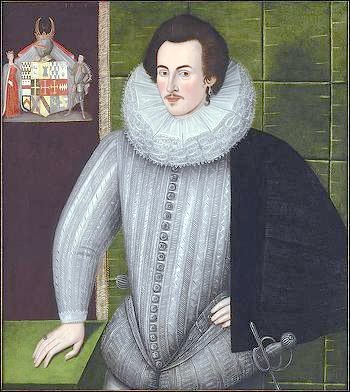

By 1595 she had begun an affair with Charles Blount, Baron Mountjoy. Penelope would have at least three children with Blount, all of whom were accepted by Lord Rich as his own – even though she would name one child Mountjoy!

Rich’s desire not to bring disgrace upon his wife was probably so as not to incur the wrath of Penelope’s brother the Earl of Essex, now the aging Queen Elizabeth’s favourite.

Created Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, Essex was sent to Ireland in 1599 to subdue the revolts there. Unable to secure peace, Essex agreed a truce with the rebels and returned to England against the wishes of the Queen. Placed under house arrest and facing ruin, Essex petitioned the Queen for mercy and was granted leave so long as he did not return to court.

And so the seeds of what became known as the Essex Rebellion were sown. In February 1601 a group of Essex’s co-conspirators met to discuss seizing the Court, Tower and city of London. On February 8th 1601 Essex and around 200 supporters marched on the city. Denounced by Robert Cecil as a traitor, Essex’s support ebbed away and he had no option but to surrender.

Tried and convicted of treason, Essex denounced many of his so-conspirators including his sister Penelope, on whom he placed most of the blame. He accused her of encouraging him to raise an army against the aging Queen in order to install King James VI of Scotland in her place. Penelope was placed under house arrest and questioned by the Privy Council. She argued that rather than being the instigator, she had acted out of love for her brother: she claimed she had ‘been more like a slave than a sister, which proceeded out of my exceeding love, rather than his authority’ The Queen decided to take no action against her.

After Essex’s execution, Lord Rich disowned Penelope and her children by Mountjoy. She then set up house quite openly with her lover.

Queen Elizabeth died in 1603 and James duly became king. It appears that their secret overtures to the king had not been in vain as Mountjoy was created Earl of Devonshire and Lady Rich became a Lady of the Bedchamber, one of Queen Anne’s ladies-in-waiting. They enjoyed great influence at court.

In 1605, Lord Rich sued for divorce. Anxious to marry Mountjoy, Penelope admitted to adultery and the divorce was granted. Her petition to remarry and legitimise her children was however refused, as the Church of England did not allow remarriage if the other spouse was still alive.

Penelope and Blount went ahead regardless and were married in a private ceremony on 26th December 1605. King James was furious and banished them both from court.

This was a time of religious and political unrest, culminating in the Catholic plot to blow up the Houses of Parliament on November 5th 1605. The Gunpowder Plotters included several members of Penelope’s extended family, most notably her sister Dorothy’s husband, the Earl of Northumberland. Implicated by association, he spent the next 17 years imprisoned in the Tower of London. His life was spared as it was accepted that he had planned to attend Parliament that day and so could not have known of the plot.

Mountjoy died a few months after the plotters’ trial in 1606. The marriage he and Penelope had undergone to help secure the passage of his lands and titles to his children was not recognised and after his death, his will was fiercely contested by his family.

In a bid to settle the will in their favour, a charge of fraud was brought against Penelope: she was described as ‘an harlot, adulteress, concubine and whore’. However before the will could be settled, Penelope died on 7th July 1607.

Lady Penelope Devereux was a complex character: on the one hand well educated, beautiful and well liked; on the other, wilful, reckless, ambitious, rebellious and recalcitrant. During her life at court she inspired many poets and artist. It is widely accepted that she was the inspiration for Sir Philip Sidney’s sonnet cycle ‘Astrophel and Stella’.