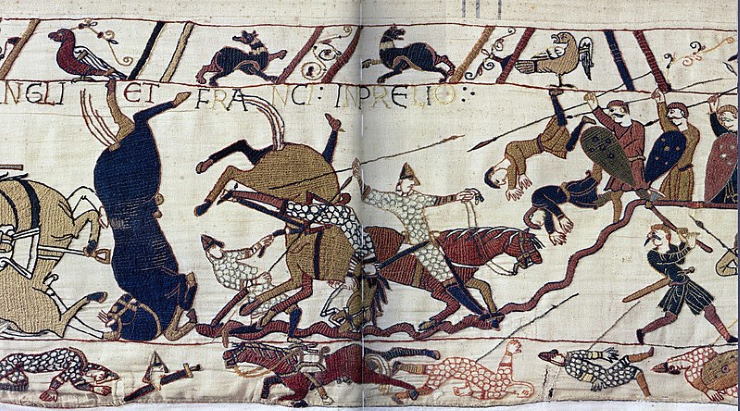

Whilst William the Conqueror was ushering in a new era of Norman domination in the British Isles, a legendary, if not somewhat elusive figure known to be roaming the fenlands, had other ideas; his name was Hereward the Wake.

An Anglo-Saxon nobleman, he led a rebellion against the Norman conquerors, taking on legendary status.

Many have tried to pin down this mysterious figure with varying descriptions of his guerrilla style leadership and status as an outlaw, but what do we really know about this Anglo-Saxon rebel who tried to take on the powerful might of William the Conqueror and his men?

Information about Hereward is scant and relies principally on information produced in “The Peterborough Chronicle” and “Gesta Herewardi” manuscript.

Hereward has since taken on a somewhat mythical presence in British historical narratives.

He is thought to have been born around 1035 and came from the Northamptonshire region of the country.

The origin of his epithet “the Wake” remains disputed, with some believing that it derives from an Old English word meaning watchful whilst others suggest it was a name given to him later by an Anglo-Norman family who claimed him as their ancestor. He had begun to be referred to as “Hereward the Wake” by the fourteenth century according to the records, whilst he has also been called “the Outlaw” and “the Exile”.

Born into a noble Anglo-Saxon family, the Gesta Herewardi manuscripts refer to his heritage as being a descendant of Oslac of York, an earl who controlled much of Northumbria.

More recent academia suggests that he was the son of an important Anglo-Danish figure whose brother was Abbot Brand of Peterborough.

Whatever his presumed noble lineage was, Hereward appears to have lived much of his life as an exile after he was condemned by his father for disobedience. Subsequently, Edward the Confessor would make the declaration that Hereward was an outlaw.

Impulsive and commanding by nature, Hereward was described by Leofric the Deacon, an English cleric and writer, as physically imposing with blond hair and light eyes as well as being agile and vigorous. In addition, his impressive physicality was thought to match his personality which Leofric describes as possessing much valour.

His impetuous nature however, had landed him in hot water with his father and as a result, as a young man he would spend his time on the continent, where he travelled to Flanders and became a mercenary fighter on behalf of Baldwin V.

Whilst he was busy learning the military skills he would need to later resist the Normans, back at home his family were in danger.

After the Norman invasion, Hereward returned home to find that his father and brother had been killed. Even more sinisterly, his brother’s decapitated head was said to have been mounted on a spike at the entrance of their property.

The family’s lands had been subsequently confiscated and given to the Norman, Ivo de Taillebois.

Enraged and engulfed by grief, Hereward swore he would avenge his father and his brother and would seek revenge on those responsible for their deaths.

He was able to fulfil his desire for retribution when he caught a group of Normans who had been mocking his fellow Anglo-Saxons and subsequently killed them in the ensuing chaos that followed the confrontation.

The following day, those fifteen dead Normans would have their heads put on spikes and replace that of his brother at the entrance to his property, a grim reminder of the bad blood between the invaded and invaders.

Soon afterwards, he journeyed to Peterborough Abbey where he was knighted by his uncle and then briefly returned to the continent where he spent time in Flanders, planning his next move.

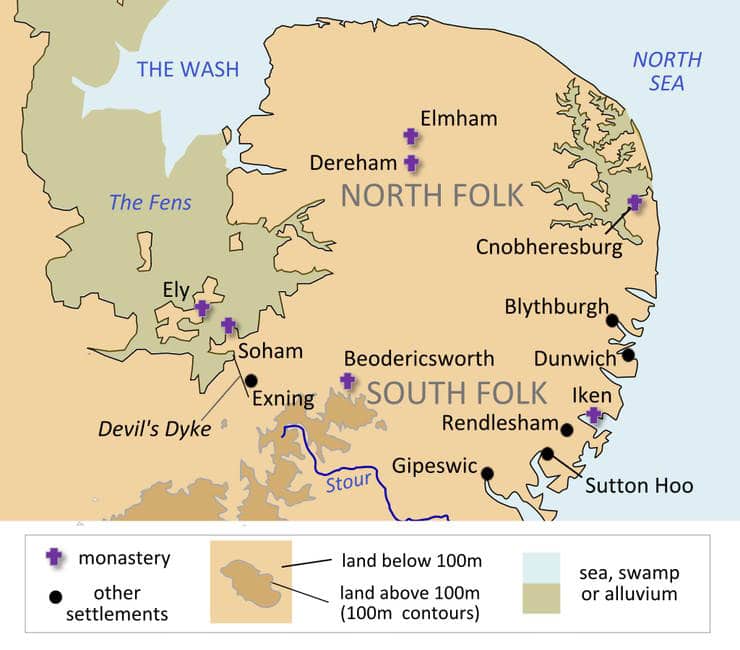

In 1070 he returned to England in order to partake in the resistance movement which was forming around a small army sent by Sweyn II of Denmark. Hereward and the followers he had now accumulated, joined the Danish soldiers and met at their base on the Isle of Ely.

Meanwhile, his uncle had been replaced at Peterborough Abbey by a Norman abbot known as Turold de Fecamp.

With Hereward, his supporters and the Danish army focused on retaking Peterborough Abbey, they subsequently launched their assault from their base at the Isle of Ely and sacked the Abbey with the intention of saving their Anglo-Saxon treasures from getting into Norman hands.

After launching this attack, they retreated back to their military base where they found themselves bolstered by new recruits. This included a small army under the leadership of Earl Morcar of Northumbria who was a fellow nobleman who had also been displaced by the Normans.

Despite the growing numbers adding to the band of resistors, William the Conqueror had now set his sights on these men encamped at the Isle of Ely and was determined to end their rebellion once and for all.

.

Such an attempt to suppress the rebels proved more difficult than William and his forces had anticipated, particularly when they launched an assault on the Isle of Ely and were scuppered when the mile-long causeway they had attempted to construct gave way.

The area of fenland was particularly difficult to navigate, and the impassable marshes known as the Aldreth Causeway was where William and his troops made their first mistake.

After constructing the long timber causeway, it soon became apparent that the weight of William’s troops was too much for the construction and it collapsed, leading to the death of many Norman soldiers by drowning.

This however was their first attempt and unfortunately for the Anglo-Saxon rebels, the Normans were not going to give up so easily.

Whilst other attempts were being planned back at the Norman base camp, legend has it that Hereward travelled to the camp in disguise and overheard their plans.

When the Norman troops tried again to construct a causeway to Ely, Hereward had already positioned his men amongst the reeds and subsequently set fire to the area, thus surrounding the Normans in flames; they now faced a fate of burning or drowning. Anyone who managed to escape also found themselves at the mercy of the Anglo-Saxon arrows which rained down on them as they retreated.

William’s men would make one final bid to take the Isle of Ely, on this occasion ensuring their success in large part due to the complicity of the Abbot Thurstan and resident monks on the island, whom they bribed in exchange for knowledge on navigating the marshes.

With this valuable information now under their belt, the Normans launched a successful attack on the island, navigating the treacherous topography and capturing the island as well as imprisoning Earl Morcar.

Despite this Norman success against their Anglo-Saxon rebel opponents, they were not able to detain Hereward and his band of men who subsequently evaded capture, escaped across the fenlands and continued with their movement against the invaders.

What happens next remains unclear, as conflicting accounts of Hereward’s fate only add to his mythological status.

The Gesta Herewardi manuscript states that he attempted negotiations with William and was eventually pardoned by him. Other sources suggest that he saw out his days in the rugged wilds of the Fenlands, losing his life at the swords of a group of Norman knights.

Whatever his eventual fate, Hereward the Wake had an enormous impact on the local people who continued to visit a wooden construction in the Fens known as Hereward’s Castle.

His rebellion, whilst unsuccessful, was a testament to the Anglo-Saxons and their fighting spirit at the hands of their now more formidable Norman opponents.

Hereward was an underdog in a losing battle against Norman might and changing power on the British Isles.

Whilst his story faded and was lost with the memories of his Anglo-Saxon compatriots, many centuries later Hereward and his intrepid tale of rebellion rose to the public consciousness once again, this time thank to the Victorian author, Charles Kingsley who wrote, “Hereward the Wake: Last of the English”. In doing so, Kingsley helped to elevate Hereward to the status of a legendary English figure, accrediting him the status of a hero.

Many even speculate whether these heroic tales would even influence later stories of Robin Hood, another legendary hero forced to live in the wild as an outlaw whilst fighting the injustices of the ruling class.

Hereward the Wake remains today an elusive figure; much like his days of roaming the countryside, Hereward continues to evade those who try to pin him down, whether in a pitched battle or on the page of a history book. What we do know however is that he lived and died as a warrior defending his lands. He was an Anglo-Saxon hero, battling against the Normans and an English legend forever.

Jessica Brain is a freelance writer specialising in history. Based in Kent and a lover of all things historical.

Published: 24th January 2023