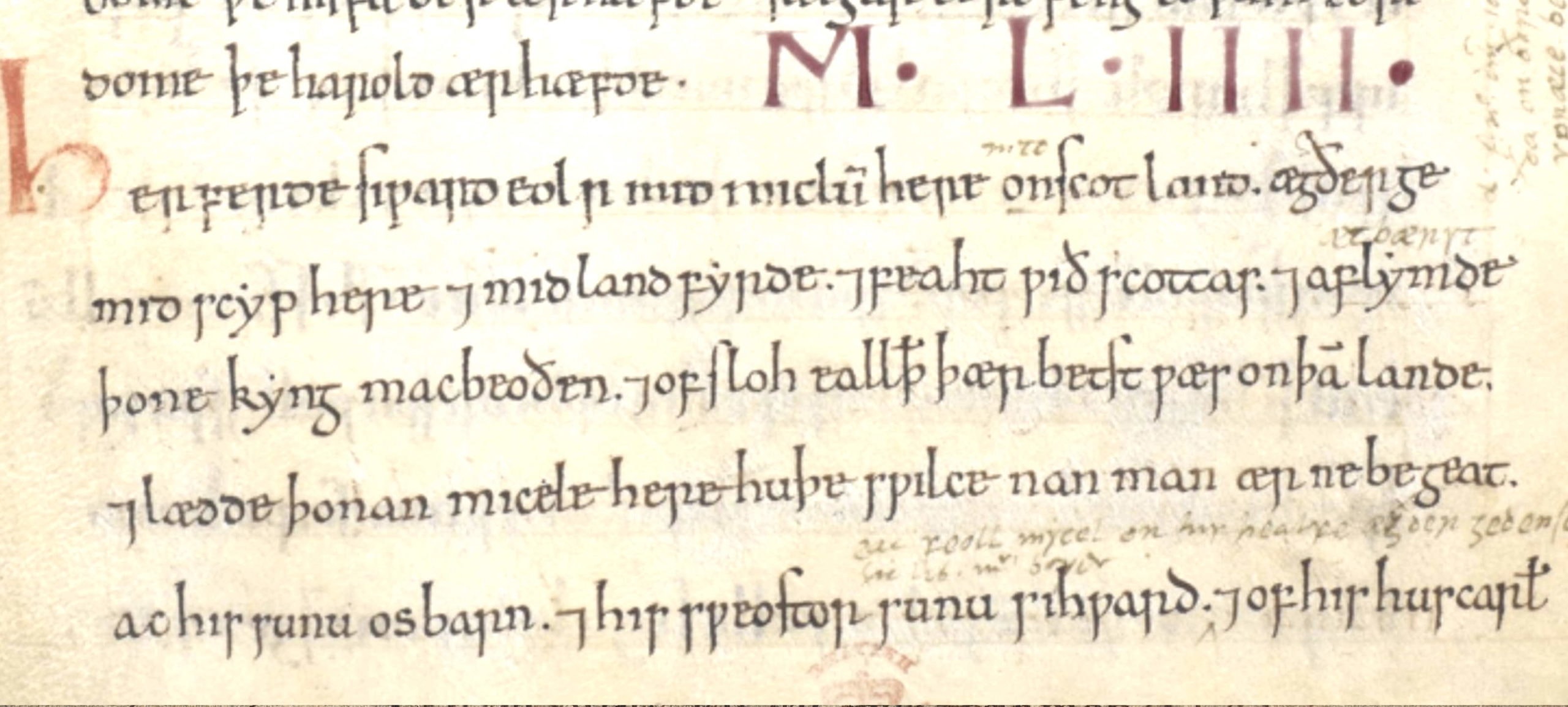

A prominent English Saxon lord from Shropshire defiantly resisted the Norman Conquest. His name was Eadric the Wild, also known as Wild Edric, a man whose resistance took on legendary status and was documented in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle.

Whilst you may have heard fanciful tales of his life in English folklore, the more horticultural amongst you might be more familiar with his name as a sumptuous pink rose called Wild Edric.

His attempts to resist the growing might of the Normans may have proved futile, however his individual efforts along with others like him contributed to myths and legends for years to come.

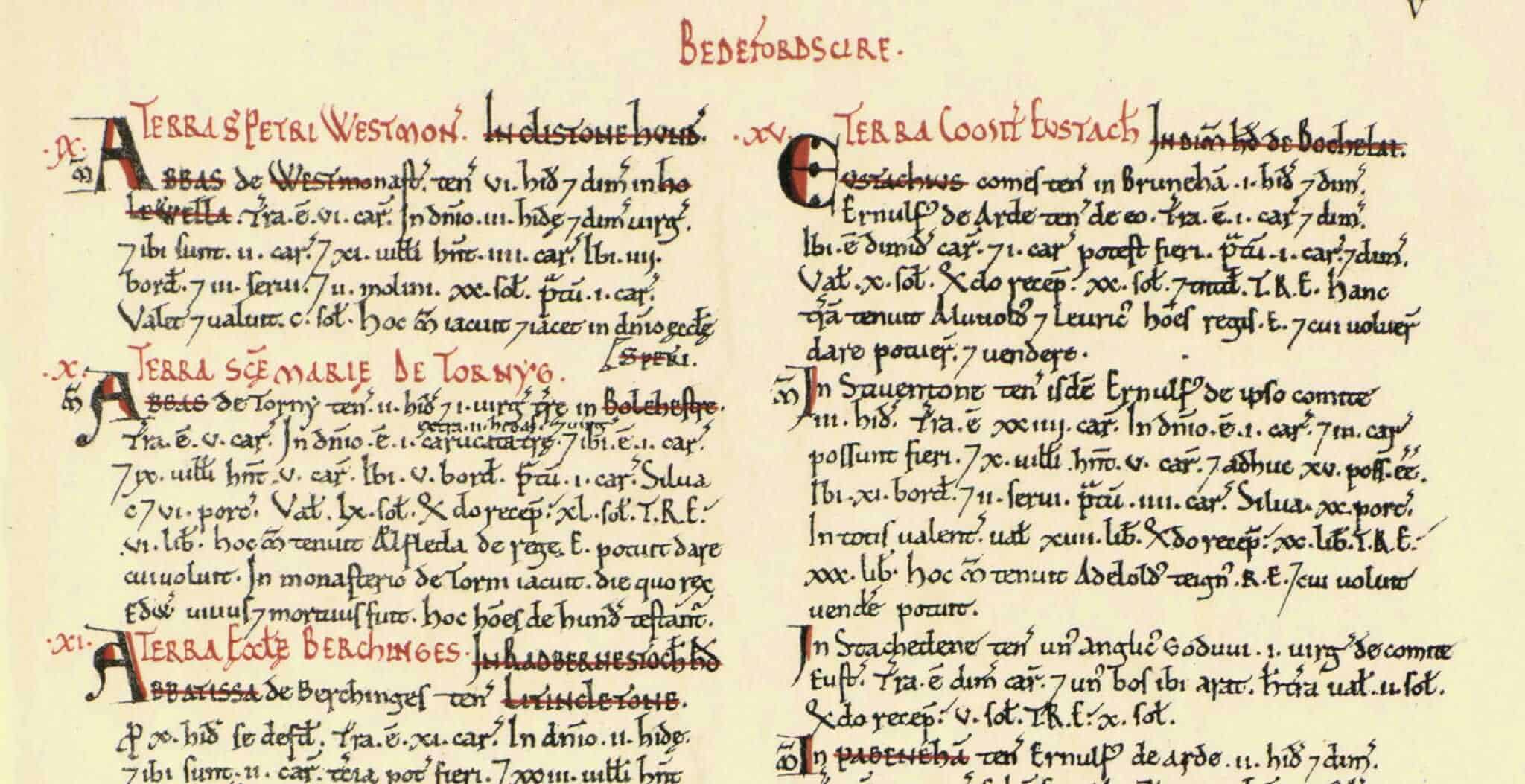

Originally from the county of Shropshire, Eadric held the position of thegn, which in Anglo-Saxon society was a high-ranking member of the nobility, only second to the ealdormen. Due to his aristocratic standing, he was in possession of vast lands which would be one of the reasons he found himself in direct opposition to the Normans, who upon their conquest began claiming vast swathes of property which had formerly belonged to Anglo-Saxons.

Eadric was in fact one of the most powerful thegns in his county with estates in both Shropshire and Herefordshire.

Whilst his exact heritage remains unconfirmed, the twelfth century historian John of Worcester described Eadric as the son of a man called Aelfric who was believed to be related to Eadric Streona, an important ealdorman of Mercia. Whilst the exact relationship remains unclear, with Aelfric believed to be either a brother of more likely a nephew to Eadric Streona, this would place Eadric as a grandson of the ealdorman, who himself was serving under King Aethelred the Unready.

Eadric and his cousin Siward would become the wealthiest thegns in Shropshire, believed to be the lords of almost sixty manors.

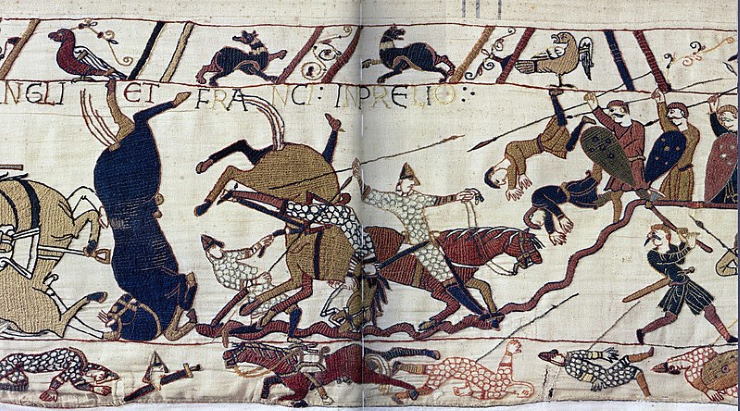

Whilst he enjoyed the Anglo-Saxon privileges such a position afforded him, his comfortable lifestyle was about to be curtailed when William the Conqueror and his men initiated their invasion of England.

With the Normans cementing their power base after their victory at the Battle of Hastings (in which Eadric is not believed to have taken part), the Anglo-Saxons were left at the mercy of the victors.

After the battle, the majority of Eadric’s manors were taken by King William and distributed amongst his own barons.

Unwilling to surrender his property, Eadric refused to accept Norman control and submit to their power, forcing a powerful response from the Normans who laid waste to his land.

As recorded in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, Eadric found himself at the mercy of Richard fitz Scrob, a Norman commander whose base was Hereford Castle.

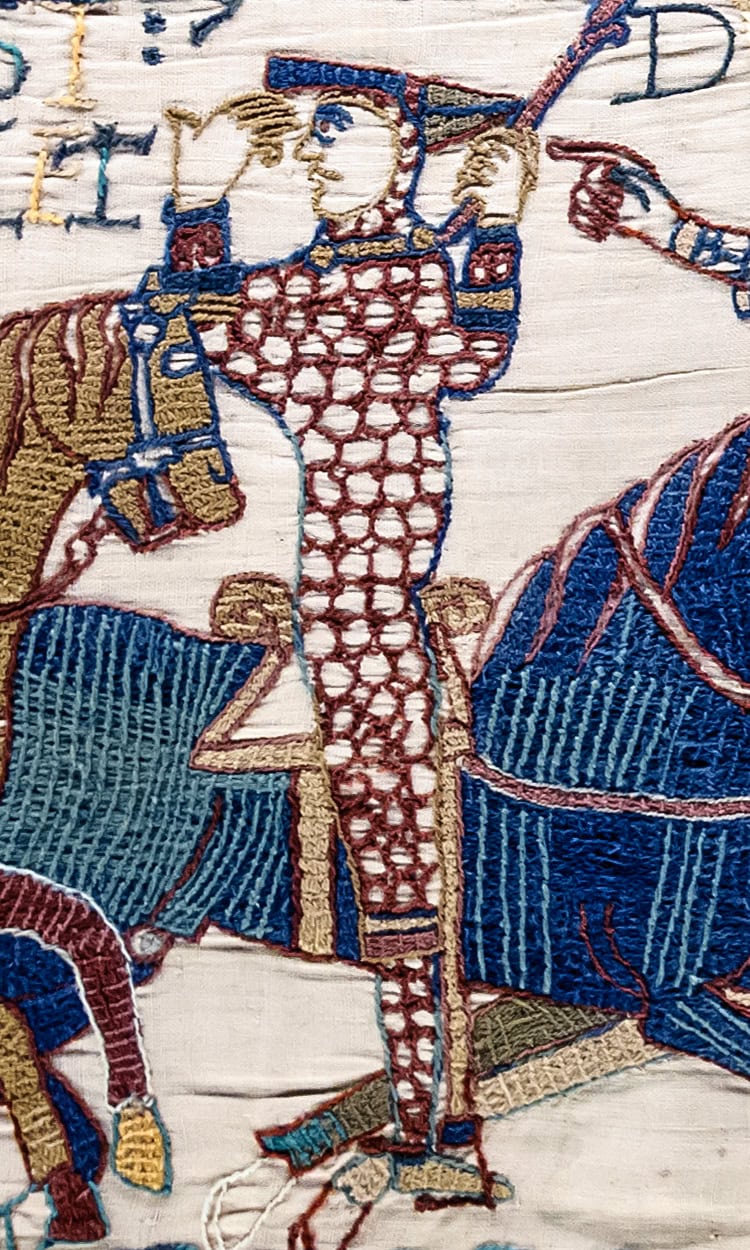

In response Eadric prepared for a rebellion, aligning himself with the Prince of Gwynedd and Prince of Powys who were prominent Welsh resistance leaders at the time. Now the three men were united in their new alliance against King William, Eadric and his Welsh allies attacked the Normans in Herefordshire, targeting Hereford but without producing the desired result of recapturing the castle.

Whilst Hereford Castle remained in Norman hands, the resistance fighters were forced to retreat and regroup in a bid to make their next effort a more fruitful one.

In the period between 1067 and 1070, a wave of rebellions broke out across the country, however Eadric’s campaigns drew the attention of the Normans who repeatedly tried to suppress his rebellious activities but to no avail.

Eadric’s refusal to recognise the new power of the Normans remained steadfast and whilst his failure to take Hereford Castle had caused him to retreat, he continued with his plans of rebellion, including burning the town of Shrewsbury.

Whilst King William took his army north in order to put down a rebellious force under the command of the Earl Mokar of Northumberland, Eadric took advantage to attack Shrewsbury.

Once again, the castle in the town became the main focal point of the battle, however the rebel forces were unable to successfully besiege Shrewsbury Castle and once more the Normans retained control.

That being said, Eadric’s efforts reflected a more widespread discontent amongst the Anglo-Saxon population, as his attempts at expelling the Normans from the area were bolstered by further troops, including his allies in Wales, as well as other rebels from the county of Cheshire.

These newly formed alliances between rebels would face the ultimate test in 1069 when William received the news of the attack in Shrewsbury. Upon hearing of another rebel assault, William swiftly called his men into action and headed south in order to confront the remaining rebels.

Although Eadric was believed to have retreated back to Shropshire, the others remained and faced William’s Norman army at Stafford but sadly faced yet another defeat at the hands of this elite fighting force.

Although victorious at the Battle of Stafford, to further punish the rebels William laid waste to the land.

In response, Eadric made his reluctant peace and submitted to William by swearing allegiance to the king.

Perhaps more surprisingly, Eadric even accompanied William during a revolt in 1075.

With Eadric’s apparent new found loyalty for the Norman king, his fellow Anglo-Saxon rebels and compatriots were less than pleased to see such a prominent figure of the resistance give in to the conquerors.

It was at the time of Eadric’s changing allegiances that rumours began to appear about how he had been imprisoned alongside his wife, Lady Godda, by fellow Anglo-Saxons who were appalled by his new found support for the Normans.

In time, these stories would evolve into legends, with tales of Eadric and his wife peppering the pages of English folklore and story-telling for years to come.

Eadric’s supposed imprisonment led to another folk legend, that of Eadric, his wife and supporters being placed in lead mines in the Shropshire hills with a curse being placed upon them. Eadric and Lady Godda would be forced to rise and defend England should she be threatened or in danger. Threat defeated, they were to retreat back to their underground incarceration to await the next threat to their land.

Such a curse would not end until England resumed its pre-Norman status, correcting all the ills committed since that time, and only then would Eadric the Wild and his wife finally be allowed to die.

This extraordinary tale has since become embedded in English folklore and has endured for centuries. There have even been alleged sightings of Eadric riding out to battle from the Shropshire hills at times of great danger, including in 1814 during the Crimean War when a local girl was said to have seen Eadric and Lady Godda charging on their horses, leading a band of warriors. Other sightings were claimed in the moments leading up to both the First and Second World Wars.

Such stories soon began to take on a life of their own, as Eadric’s status as a warrior trapped in a curse allowed him to become associated with the widely known legend called “the wild hunt”. This legend can be found across much of northern Europe and has become a prominent feature of folkloric tales across cultures. The wild hunt refers to sightings of mythological phantom horsemen and their dogs charging across land or sky in pursuit of lost souls or recently deceased souls to carry away with them. Over time, the leader of this phantom hunt has been associated with various historical figures.

Other folklore associated with Eadric includes the tale of “the fish and the sword”, based at Bomere Pool in Shropshire where a monster fish is said to be in possession of the sword of Eadric the Wild and whenever anyone attempts to catch it, the sword allows it simply to cut itself free. According to the legend, when the rightful heir of Eadric the Wild appears, the sword will be presented; until then the fish remains an elusive presence in those waters.

Perhaps one of the most well-known tales of Eadric concerns his wife Lady Godda, who is said to not be human but instead a fairy princess who agrees to be his wife as long as he is good to her and never admonishes her. Within this tale they were said to have had many happy years together until one day he breaks his promise and despite his great pleas for forgiveness she instantly disappears and he is left to waste away, dying in great sadness and grief for the loss of his loved one.

In reality, the real-life Anglo-Saxon rebel’s last days remain a mystery.

Much like the legends and folklore in which he appears, Eadric the Wild remains an elusive figure, an Anglo-Saxon rebel still roaming the hills of Shropshire, cursed, trapped or simply an apparition in times of struggle.

Jessica Brain is a freelance writer specialising in history. Based in Kent and a lover of all things historical.

Published: 10th February 2023