In 1128, the French nobleman Hughes de Payens visited England with a mission; to gather men and funds for the Crusades. His visit would mark the beginning of the history of the Knights Templar in England and thus a new and enduring chapter in the history of medieval England, its involvement in one of the biggest and most defining periods in Christian and Islamic relations: the Crusades.

“Deus lo volt” (Deus Vult) – God wills it!

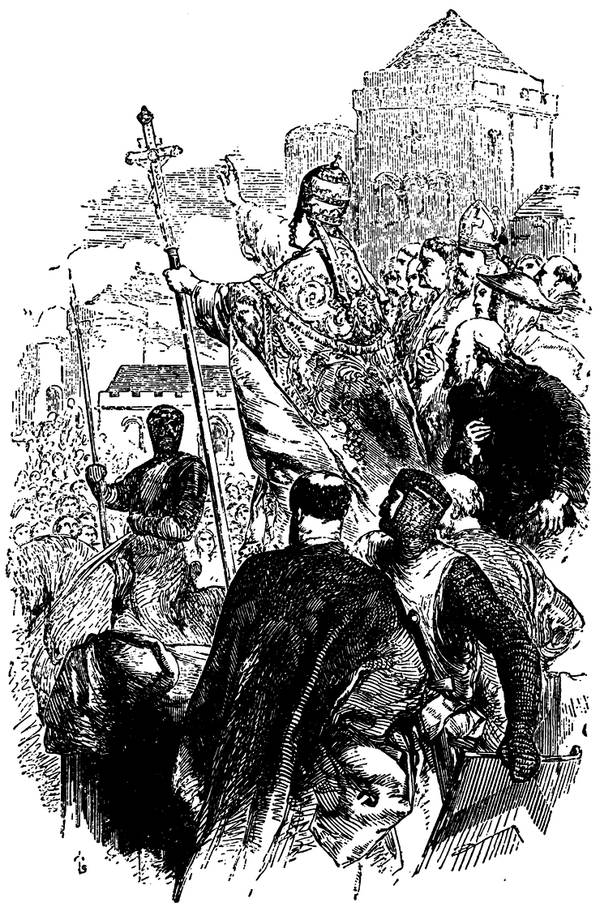

These were the words spoken by Pope Urban II at Clermont as he urged his fellow Christians to rise up against the threat of the infidels who were encroaching on the Christian world.

Whilst the British Isles was further than most from the frontline of such a war, in the centuries to come many of its citizens would participate in its wars, including English medieval kings.

Such a stirring call to arms was followed by spontaneous offers to join the fight from all stratas of society.

Across the European continent men, women and children volunteered themselves and collectively formed part of the movement, as it shaped attitudes, ideas and the evolution of the military in the medieval world.

Whilst the announcement at Clermont officially marked the beginning of the First Crusade, its origins can be traced back much further in time and to an eastern Christian civilisation which found itself on the frontier of Muslim expansion: the Byzantine Empire.

The Eastern Roman Empire, later more commonly referred to as the Byzantine Empire, was an imperial giant of the early medieval world and existed for almost 1000 years, long outlasting its western Roman counterpart. At its epicentre was Constantinople which became the nucleus of economic, cultural and military power in the realm.

Throughout its long history, Byzantium’s borders changed with the ebbs and flows of its power, however at its height, during the reign of Justinian I, it reconquered much of the Mediterranean including parts of northern Africa and Italy. At its peak, the Byzantine imperial reach extended from the far western stretches of Europe in southern Spain, all the way to Syria in the Middle East.

Such power however would not go unchallenged. In 602, the empire would find itself facing a great threat during the Byzantine-Sassanian War which ended in 628. Moreover, as the Muslim conquerors continued to garner success, Byzantium was exhausting its resources whilst desperately fighting off growing Islamic power in the region. By the 7th century Egypt and Syria were lost to the Rashidun Caliphate; Jerusalem was captured in 637 and then its African territory was taken by the Umayyads in 698.

By the ninth century however, a renaissance of Byzantine power allowed the empire to expand once more under its Macedonian dynasty, with its territory stretching as far as Iran.

Unfortunately for the people of Byzantium, this imperial reach once again came under threat and this time from a growing and formidable force: the Seljuk Turks.

During the tenth century, the demographic and political landscape was changing in the Middle East with the arrival of the Seljuk Turks. Initially a small ruling clan, they had recently converted to Islam and began to conquer large territories including Iran and Iraq.

Meanwhile, Byzantium had been experiencing its own internal struggles, the East-West Schism of 1054 solidifying the differences between East and West Christendom. As part of this split, the Byzantine Empire faced just as much hostility from its Western Christians as it did from its Muslim neighbours.

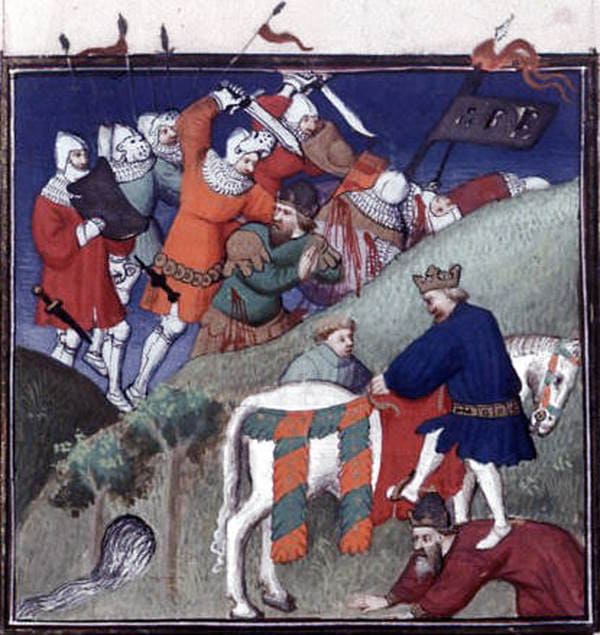

All these problems came to a head in the year 1071 when Byzantium experienced a considerable military defeat at the Battle of Manzikert (Malazgirt) at the hands of the Seljuk Turks.

The Byzantine defeat and subsequent capture of Emperor Romanus Diogenes dealt a considerable blow to restoring its economic, military and international status. On the other hand, it allowed for an intensifying growth of Turkish power with victory at Manzikert providing a gateway to control of Asia Minor.

With the Byzantine army (including several mercenary soldiers made up of Normans, Vikings and Slavs) crushed, chaos ensued back in Constantinople with Turkish adventurers emboldened by their victory whilst Byzantine infighting only solidified its precarious hold on power.

It would take another few decades before unity in the empire was restored, thanks to the influence of Emperor Alexius (Alexios) Comnenus who made it his mission to restore stability and unify his people against a common enemy.

It would soon become clear however that in order to do this, he needed assistance in the form of military power from elsewhere and so he made his request for his Christian counterparts in the west to assist him in this battle.

Such a call to fellow Christians in need was not unheard of, as French and Italian nobles had volunteered their services to help the Christians in Muslim-dominated Spain.

Pope Urban II would receive this request at the Council of Piacenza where he met with ambassadors sent by Emperor Alexius to make the case for Christian unity against the growing power of Islam in the region.

The previous Pope, Gregory VII had already been drawing up plans, which involved the liberation of the Holy Land. Two decades later, Alexius’s request would give Pope Urban II many issues to ponder.

After careful consideration, the idea of the Crusades began to take root in his mind and would soon be realised at the Council of Clermont in November 1095.

Clermont was intended to be a council concerned with clerical matters, however it soon became the launching pad for the Crusades.

The policy of “The Truce of God” was also on the agenda and involved the promotion of peace between different Christian leaders in Europe who, since the schism, had been quarrelling amongst themselves. A united Christian front to ensure peace in their domain became the dominant theme of the meeting.

All such themes found themselves to be expressed by Pope Urban II in his rousing address in which he spoke of maintaining the “Peace of God” and assisting their fellow Christians in the east:

“Let all hatred depart from among you, all quarrels end, all wars cease. Start upon the road to the Holy Sepulchre to wrest that land from the wicked race and subject it to yourselves.”

And so it was, on 27th November 1095, that the crowd heard his words and a new chapter of Christian and Islamic relations began, one that would continue for centuries to come and dominate not only the Middle East but the development of Europe and the Christian world as a whole.

Jessica Brain is a freelance writer specialising in history. Based in Kent and a lover of all things historical.

Published 16th March 2023