Today, Cecily of York is far less well-known than her older sister Elizabeth of York, the first Tudor queen. Yet her own story remains fascinating, intertwined not only with the bloody conflict known as the Wars of the Roses, and the subsequent rise of the Tudor dynasty, but also with great personal tribulations

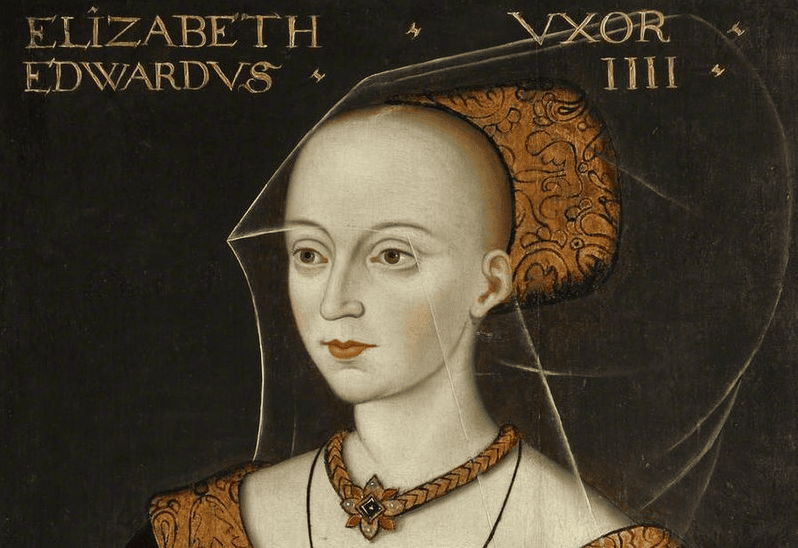

It was on 20th March 1469 that Cecily was born to King Edward IV and Elizabeth Woodville, being the third of eight children to survive infancy. Her father had won the English crown through the Battle of Towton in 1461, the House of York triumphing over the House of Lancaster after years of civil war. If it appeared the political situation had finally settled down, however, this was not to last: when Cecily was just one year old, a rebellion involving her uncle George Duke of Clarence forced King Edward into exile, whilst Elizabeth Woodville sought sanctuary with their children in Westminster Abbey.

In 1471, once her father had been restored to power, Cecily’s upbringing commenced. It entailed what could be expected for a late-medieval princess: she learnt how to read and write — although her handwriting was said to be atrocious — as well as to dance and embroider. It appears she did not know Latin but did learn French. Like several of her sisters, Cecily was also being prepared for the role of a high-status wife. Specifically, Edward IV intended to make her queen of Scotland, hoping it would advance his political objectives.

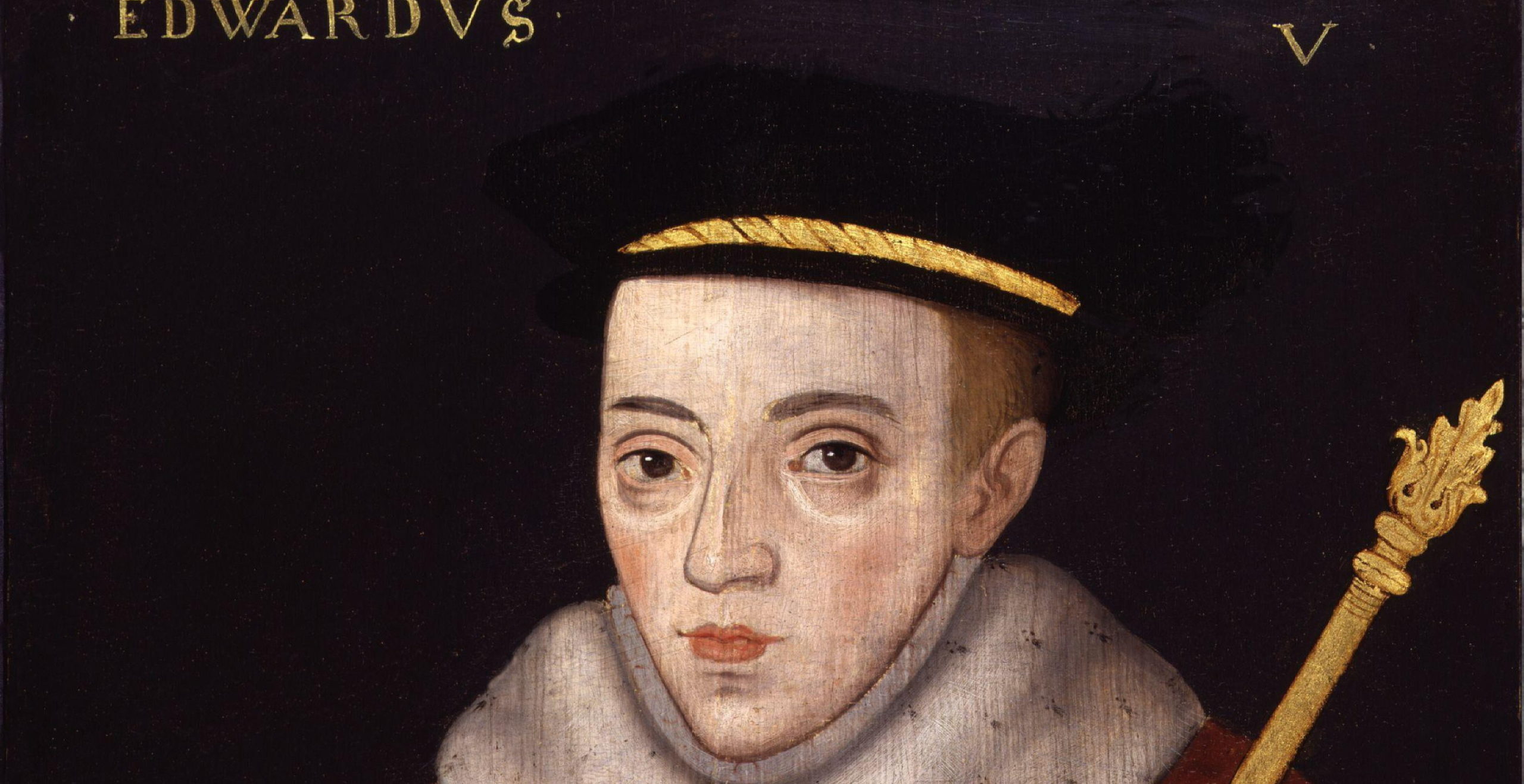

This plan was disrupted in April 1483, when the forty-year-old king died from what was likely pneumonia or typhoid. Shortly thereafter, Edward’s brother and confidante Richard Duke of Gloucester was named Lord Protector of Cecily’s own brother, Edward V. Seeking to curb the influence of the Woodville family, Richard proceeded to arrest Cecily’s uncle Anthony Woodville and her half-brother Richard Grey. Both men would be executed on charges of treason on 25th of June. Already upon hearing of their arrests, though, Elizabeth Woodville again fled to Westminster Abbey, taking her remaining children — except the absent Edward V — with her.

This time in sanctuary, aged fourteen, Cecily would have been aware of the danger she and her family potentially faced. On 4th of May, the Lord Protector escorted the new king into London, and on 16th of June the Archbishop of Canterbury convinced Elizabeth Woodville to surrender her youngest son so that he could attend the coronation.

Only a few days later, though, Cecily and her siblings were declared illegitimate, after which Richard of Gloucester himself accepted the crown as Richard III. Cecily’s brothers, meanwhile, were not seen again after the summer of 1483. Their fate remains a topic of tantalising speculation: many, including contemporary Tudor propagandists, have claimed that Richard III murdered them, while others believe they died at the hands of Henry VII’s mother Margaret Beaufort or the Duke of Buckingham, or that they escaped.

Most likely assuming that her sons had died on Richard’s command, Cecily’s mother plotted with Margaret Beaufort regarding the future of their houses and indeed the kingdom. As a result, on Christmas Day 1483, the exile Henry Tudor formally pledged that upon invading England and seizing the throne, he would marry Cecily’s sister Elizabeth. If Elizabeth died or was for any other reason unavailable, he would wed Cecily instead. Cecily, therefore, might herself have been the first Tudor queen.

In March 1484, Richard III swore not to harm the princesses in Westminster Abbey, leading them and their mother to finally emerge from sanctuary. While Elizabeth of York was then brought to court, Cecily and her sisters were taken to live at Sheriff Hutton in North Yorkshire. Because Cecily was Henry Tudor’s ‘spare bride’, however, Richard III wished to ensure she would not make this or any other threatening match. She was therefore humbly married off to Ralph Scrope, a mere younger son of the 5th Baron Scrope of Marsham.

Not long after, in the summer of 1485, Henry Tudor invaded England, and on 22nd August Richard III was slain at the Battle of Bosworth. In November the same year, Henry VII had the Titulus Regius — the act of Parliament ratifying that Cecily and her siblings were illegitimate — repealed, and in 1486 he married Elizabeth of York. Yet he wanted to bind his new in-laws even closer to his own supporters. Therefore, he had Cecily’s union with Ralph Scrope annulled, and in late 1487 she instead married Henry’s half-uncle, John Welles 1st Viscount Welles. The newlyweds may have gone to live in Tattershall Castle, an impressive red-brick residence in Lincolnshire, and we know they had two daughters, Elizabeth and Anne. What happened to these girls is uncertain, but since their marriages are not recorded they likely died in childhood, possibly in 1498 and 1499.

Whether Cecily and Welles’ marriage was a happy one is another open question. The fact that they had been loyal to the houses of York and Lancaster respectively, and that Welles was nineteen years Cecily’s senior, suggests it may not have been the most affectionate of bonds to begin with. By the time Welles himself died in 1499 or 1498, however, his will spoke lovingly of Cecily and entrusted her with his lands and castles. At this point she likely returned to court, a wealthy thirty-year-old widow, once more taking up position in her sister Elizabeth’s household.

Having carried Prince Arthur at his christening in 1486, in November 1501 Cecily carried Catherine of Aragon’s train at her and Arthur’s wedding.

The Tudor dynasty was now, if not entirely secure on the English throne, at least firmly established. Henry VII had eliminated the threat of two pretenders: Lambert Simnel, supposed to be Cecily’s cousin Edward 17th Earl of Warwick, and Perkin Warbeck, claiming the identity of her youngest brother Richard Duke of York. Moreover, the king had executed the actual Edward of Warwick in 1499, after imprisoning him from the age of ten.

It may have been this continued suspicion towards the Yorkists that prompted Cecily to once more leave court. It may also have been a love match: sometime between late 1502 and early 1504, she married the esquire Thomas Kyme, a man far beneath her station, and settled on the Isle of Wight. Henry VII clearly condemned this unconventional marriage, confiscating Cecily’s lands, though Margaret Beaufort convinced him to return part of them for the remainder of Cecily’s life. With Thomas, Cecily had at least one daughter, Margaret, and one son, Richard. Judging by a later heraldic visitation, both appear to have reached adulthood and married. However, neither received titles or property from the Tudor family despite being cousins of Prince Arthur and Henry VIII, likely showing how just far Cecily had alienated herself from court.

On 24th August 1507, the Plantagenet princess died of unknown causes at the age of thirty-eight. She was buried either in Quarr Abbey, which was demolished during the Reformation, or at the friary at King’s Langley. Thomas Kyme, meanwhile, may have outlived her by up to twenty-six years.

Saga Hillbom is the author of Princess of Thorns (2021), a novel following Cecily of York’s life, which you can read more about here: https://sagahillbom.blog/wip-coming-in-2021/ . Currently, she is a final-year History undergraduate at the University of Oxford, writing her thesis on fourteenth-century romance and love tokens.

Published: 13th October 2024.