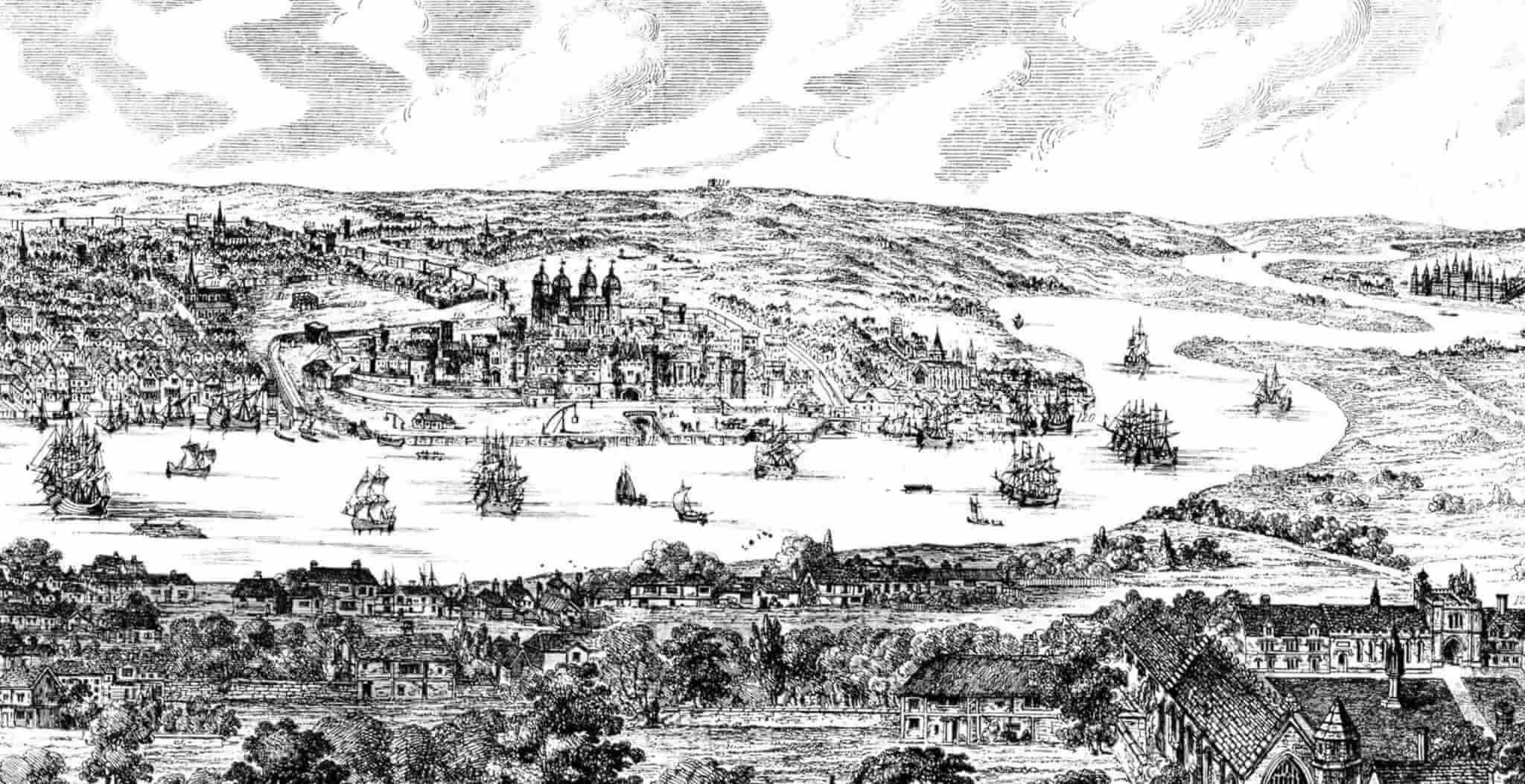

If you had been in London on Saturday 22nd June 1861, no doubt you would have made your way, with thousands of other sightseers, to watch the Tooley Street Fire burn its way from Cotton’s Wharf, which was eventually destroyed, through to Hay’s and other wharfs and warehouses to Tooley Street shops.

Omnibuses were packed: “Men were struggling for places on them, offering three and four times the fare for standing room on the roofs, to cross London Bridge”(1) and: “..every inch of room on London Bridge was crowded with thousands and thousands of excited faces”(2). Also reported: “Peripatetic vendors of ginger beer, fruit and other cheap refreshments abounded and were sold out half a dozen times over. Public houses, in defiance of Acts of Parliament kept open all night long, and did a roaring trade”(3).

It is estimated some 30,000 spectators came from all over the city. By late evening the fire stretched from London Bridge to Custom House. Properties destroyed included offices, an American steamer, four sailing boats and many barges as “..burning oil and tallow poured in cascades from the wharfs and flowed out blazing on the river”(4).

Tooley Street Fire, Day One (c) Steven C. Dickson, Creative Commons

It was shortly after 4 p.m. on this Saturday when smoke was first seen coming from the third floor of Cotton’s Wharf warehouse and word was send to the headquarters of the London Fire Engine Establishment (LFEE) in Warling Street. By 6 p.m. 14 fire engines, including a steam fire engine and a floating engine were all at the scene. The flames spread so fiercely and so rapidly that fire engines from all over the country arrived to help the LFEE, including private works brigades.

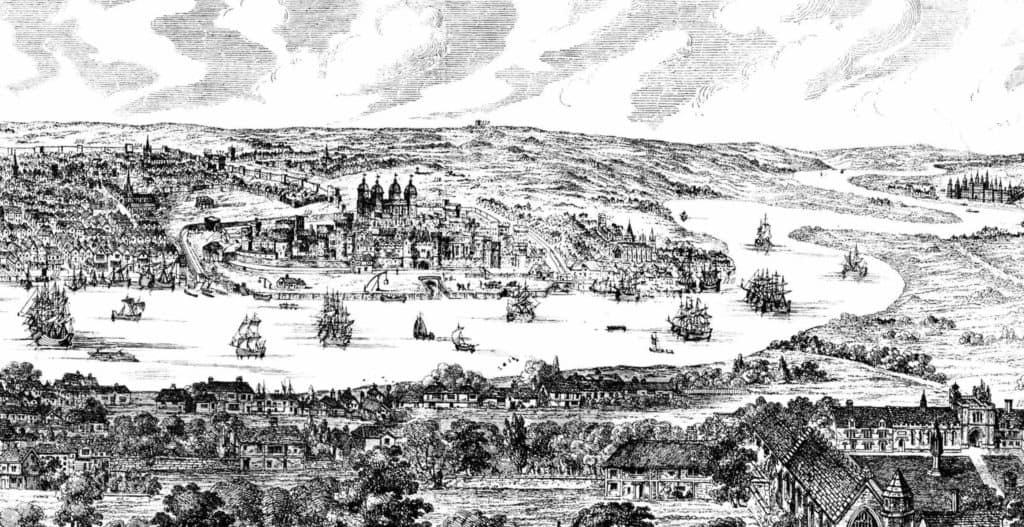

It took two weeks to put the fire out at an estimated cost of £2 million. The fire consumed some twenty warehouses containing 5,000 tons of rice, 10,000 barrels of tallow, 1,000 tons of hemp, 1,100 tons of jute, 3,000 tons of sugar and 18,000 bales of cotton, as well as huge quantities of bacon, tea, spices and other merchandise. It also consumed some 500 tons of saltpetre, which is used in gunpowder and also as a food preservative. Many barges on the river were also destroyed.

There were two reasons why the fire was able to spread so quickly. The first was that firefighters were unable to get a supply of water for nearly an hour due to the River Thames being at low tide. The second was that the iron fire doors, which separated many of the storage rooms in the warehouse, had been left open. It is believed that had they been closed, as recommended by James Braidwood, the Superintendent of the LFEE, the fire could have been contained, avoiding disaster.

Tooley Street Fire, End of Day Two (c) Steven C. Dickson, Creative Commons

In fact the principles of fire-fighting established by Braidwood still apply to this present day. He originally trained as a surveyor in Edinburgh and it was this background that gave him knowledge of the behaviour of building materials. He recruited expert tradesmen such as plumbers, slaters, carpenters and masons, who could apply their various fields of expertise to fire fighting.

Sadly he lost his life on that day in the Tooley Street fire. He noticed some of his firefighters tackling the blaze were becoming tired and ordered every firefighter to receive a ‘nip’ of brandy. The front section of a warehouse collapsed on top of him, killing him instantly while he was assisting one of his firefighters. Due to the intensity of the flames his body wasn’t recovered for three days, yet ironically was untouched by fire.

Upon hearing of the news of the LFEE Superintendent’s death, Queen Victoria wrote in her diary: “poor Mr Braidwood … had been killed…and the fire was still raging. It made one very sad”. Other casualties included Mr. Peter Scott who was killed at the same time as James Braidwood, as well as four men who were collecting tallow in their boat when it was swamped by burning oil which led to the death of all of them.

Engraving of James Braidwood, 1861 (c) Steven C. Dickson, Creative Commons

James Braidwood was buried at Abney Park Cemetery on 29th June 1861, alongside his stepson, also a firefighter who had been killed five years earlier in the line of duty. Shops were closed with crowds lining the route of the funeral procession for one and a half miles. The buttons and epaulettes from his tunic were removed and distributed to the firefighters of the LFEE. In 2004, a group of former London Firefighters decided to form a new Masonic Lodge and chose to name the lodge as Braidwood Lodge Number 9802 in remembrance of his life and death.

Following the Tooley Street fire, insurance companies raised their premiums and insisted on better storage of products in warehouses. In 1862 they informed the then Home Secretary, Lord Grey, that they would no longer be responsible for the fire safety of London as they had often put out fires without charge. As a result of this, in 1865 the Metropolitan Fire Brigade Act was passed which stated that from 1st January 1866 the Metropolitan Fire Brigade would commence as a public service.

There is a statue of James Braidwood in Edinburgh, where as a young man he trained as a surveyor. It was about this time that he published what is regarded as one of the first text books on the science of fire engineering, ‘On the Construction of Fire Engines and Apparatus’, and was officially re-published as a second edition in 2004. He also wrote ‘Fire prevention and fire extinction’, published posthumously in 1866.

(1)Arthur Munby, Diary 22 June 1861

(2)Arthur Munby, Diary 22 June 1861

(3) Reynolds Newspaper, June 30th 1861

(4) Arthur Munby, Diary 22 June 1861

Rita Appleby is a freelance writer and journalist, with a degree in Social Science and a particular interest in history.