When the war broke out in September 1939, it was thought by military experts and politicians that Gibraltar, as during the First World War, was not going to be in the front line of hostilities. However when the Low Countries were overrun in May 1940 and Italy entered the war on the German side in June 1940, it became clear that the war scenario in Gibraltar was going to be very different to that of the First World War.

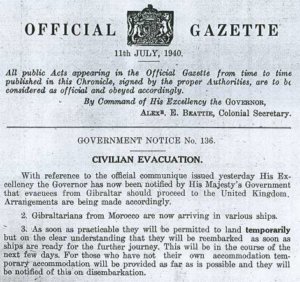

Given this, the British Government ordered the evacuation of women, children, the elderly and infirm to French Morocco, which was at that time the nearest Allied country. The main reason for this was that Gibraltar had to be converted into a fully-fledged fortress. Hitler was planning to capture Gibraltar with Spain’s assistance and if successful, it would have completely changed the outcome of the Second World War.

Soon after the arrival of the evacuees in French Morocco, France capitulated. The evacuation of Gibraltarian evacuees to French Morocco was discontinued and those who were already in French Morocco were de facto living in enemy territory. After the destruction of the French Fleet at Oran by the Royal Navy, the Gibraltarian evacuees were ordered to leave French Morocco within 24 hours.

Coinciding with the expulsion of the Gibraltar evacuees, 15,000 French troops arrived at Casablanca on British cargo ships from the UK. The French authorities in Casablanca threatened to impound these ships unless they left immediately with the Gibraltarian evacuees. The officer in charge of these ships, Commodore Creighton, pleaded with the French authorities for time to clean and replenish the ships with food and water. The request was flatly refused and the evacuees, mainly women, children, the elderly and infirm, were forced on board with rifle butts by French troops standing on the quayside There were many dramatic scenes with reports of women fainting in the heat of the sun.

The British Government who had ordered the evacuation did not want the evacuees to return to Gibraltar. However, Commodore Creighton ignored the instructions from the Admiralty and sailed to Gibraltar with all the evacuees. On arrival at Gibraltar the evacuees were not allowed to disembark. Again Commodore Creighton insisted that the ships had to be cleaned and replenished with food and water for what was going to be a very long journey across the Atlantic. By then both the Italian and Vichy French air forces were bombing Gibraltar, with many civilian and military casualties. Eventually attempts were made to make the ships holds habitable, but the facilities provided were extremely rudimentary with no medical facilities at all and with hardly any life saving equipment. They sailed out into the Atlantic, trying to avoid the U-boats, with just one escort ship.

The main problem for those on board the ships was hygiene. Many were seasick and water was strictly rationed. After six days it was discovered that due to poor storage conditions, all the provisions had become inedible. Babies born during the voyage were delivered by the evacuees themselves and some of the elderly passengers died, to be buried at sea. To avoid the menace of the German U-boats, the ships had to circumnavigate across the Atlantic taking 16 days to reach the ports of Liverpool, Swansea, Cardiff and Bristol which were also being bombed by the Germans. The entrances to these ports were mined and the ships carrying the evacuees had to navigate with great care in order to disembark safely. Commodore Creighton stated in his book ‘Convoy Commodore’ that if the convoy of ships carrying the Gibraltarian evacuees had have been attacked, it could have resulted in one of the worst disasters in British maritime history.

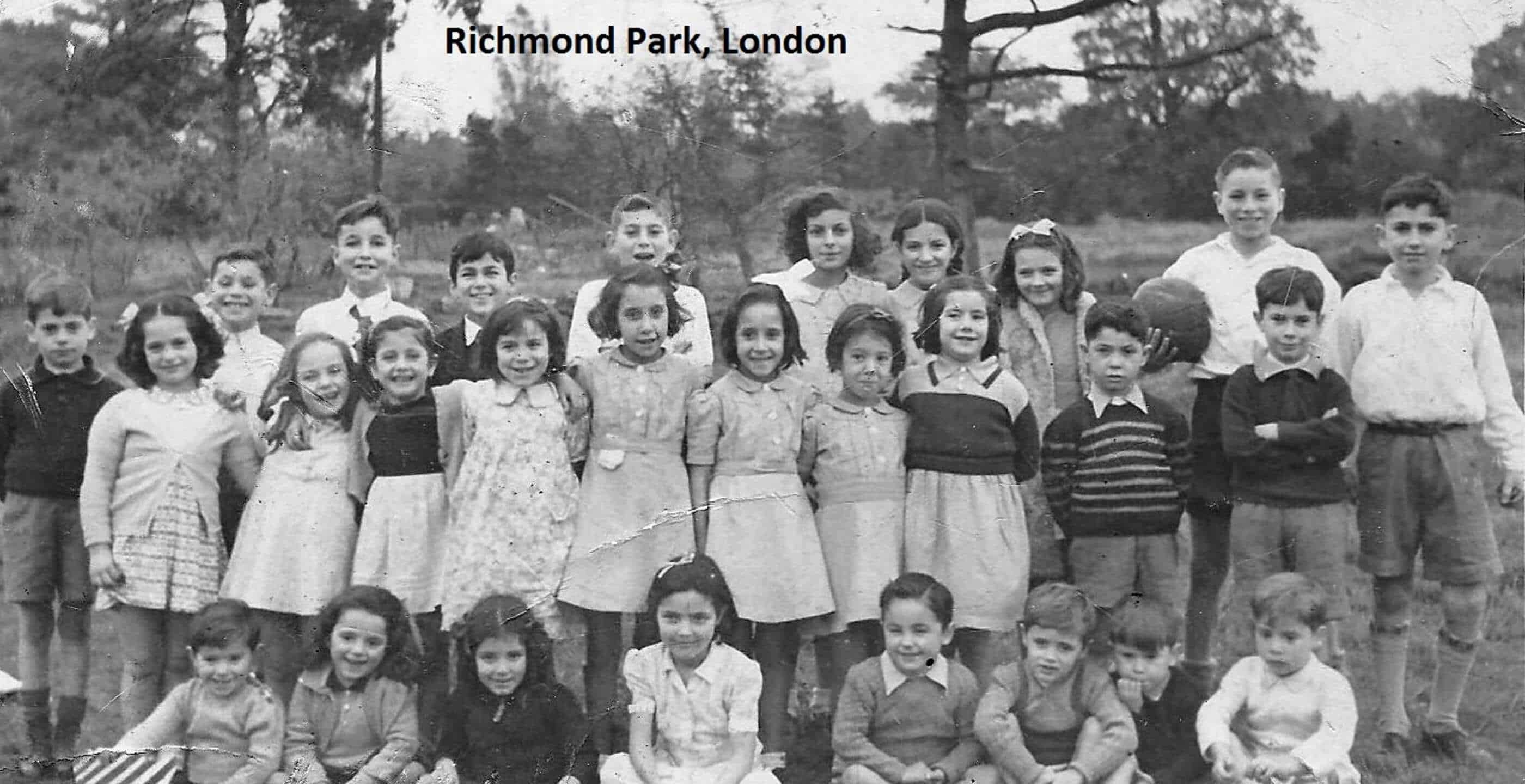

The ultimate destination of the Gibraltarian evacuees was London. The evacuees arrived in London at the time of the Blitz and when the Battle of Britain was in full swing. About 13,000 Gibraltar evacuees lived in London during the war, experiencing years of bombing as well as V1 attacks. Not all spent the war years in London: around 1,500 Gibraltarian evacuees were taken to Jamaica and a further 2,000 were sent to Madeira.

I was one of the thousands of children evacuated to London and I still have vivid memories of those terrible years in London. Because of the bombing, my family had to be moved about six times during our four years in London. Whilst we were living in central London, there were some casualties from the flying bombs among the Gibraltar evacuees. One of the first flying bombs to hit London fell close to the York Hotel by Oxford Street where my family was accommodated. I still remember the explosion and my mother, my two brothers and l lying on the floor of the hotel room as a result of the bang.

At the end of the war, half the evacuees returned to Gibraltar to join their families. The remaining half went to live for four years in camps in Northern Ireland to await their gradual repatriation. Although the camps were safer and quieter than London, the living conditions in the Nissen huts left a lot to be desired. The evacuees, while appreciative of the hospitality extended to them by the people of Northern Ireland, did not fancy the thought of spending many winters there with no prospect of finding work. Due to the prolonged waiting period, around 2,000 of the 7,000 evacuees sent to Northern Ireland left the camps of their own accord, desperate to find work in London where they eventually settled.

After the war there was an acute shortage of accommodation in Gibraltar with poor medical and educational facilities. Because of this, for many evacuees it was ten years after the evacuation before they could rejoin their families in Gibraltar.

During the war, Gibraltar was vital for the Allied forces, particularly during Operation Torch, the invasion of North Africa by Allied forces. When General Eisenhower was placed in command of Operation Torch from his underground office in Gibraltar, he told General George Marshall that without Gibraltar, Operation Torch would not have been possible. Some historians have qualified Gibraltar’s importance to the extent that without Gibraltar, Britain would have lost the war. In a strictly fortress scenario, there was no place for non-combatant civilians: they co-operated fully with a forced evacuation in order to allow Gibraltar be occupied by Allied troops.

By Joe Gingell. Very little seems to be known about the story of the Gibraltar evacuees. I have carried out a profound research about the Gibraltar evacuees and published a book in aid of cancer charities. The book can be downloaded here: Gibraltar Government National Archives – Evacuation. https://www.nationalarchives.gi/gna/NamesEvac.aspx