In the last years of Queen Victoria’s reign, the aging monarch developed a close bond with an Indian attendant called Abdul Karim. Unusual for the era, against all the social norms, the man who began life in the royal court as a servant rose to become one of her most trusted confidants and advisors.

Their friendship was not well-received in the royal household, particularly when she lavished him with honours and privileges which frustrated members of her court.

After becoming Empress of India, Queen Victoria became fascinated with all things Indian and thus Abdul Karim assumed a new role as a ‘munshi’ (teacher) for the monarch, educating her in his language, culture and traditions. At her royal residence of Osborne House, the Durbar Wing was dedicated to her new found appreciation of Indian culture, adorning the rooms in ornate Indian styles with portraits depicting Indian landscapes and people.

The driving force behind this was Abdul Karim, a man who had won the affections and trust of Queen Victoria and enjoyed the special privileges she bestowed on him as a result. The lavish lifestyle in which he had grown accustomed however was a far cry from his humble beginnings back in India.

Born near Jhansi, he was the second of six children born to Haji Wuzeeruddin who was a hospital assistant. His father’s job offered him some perks and as a result he was able to hire a tutor for his young son which allowed Karim to become fluent in both Urdu and Persian.

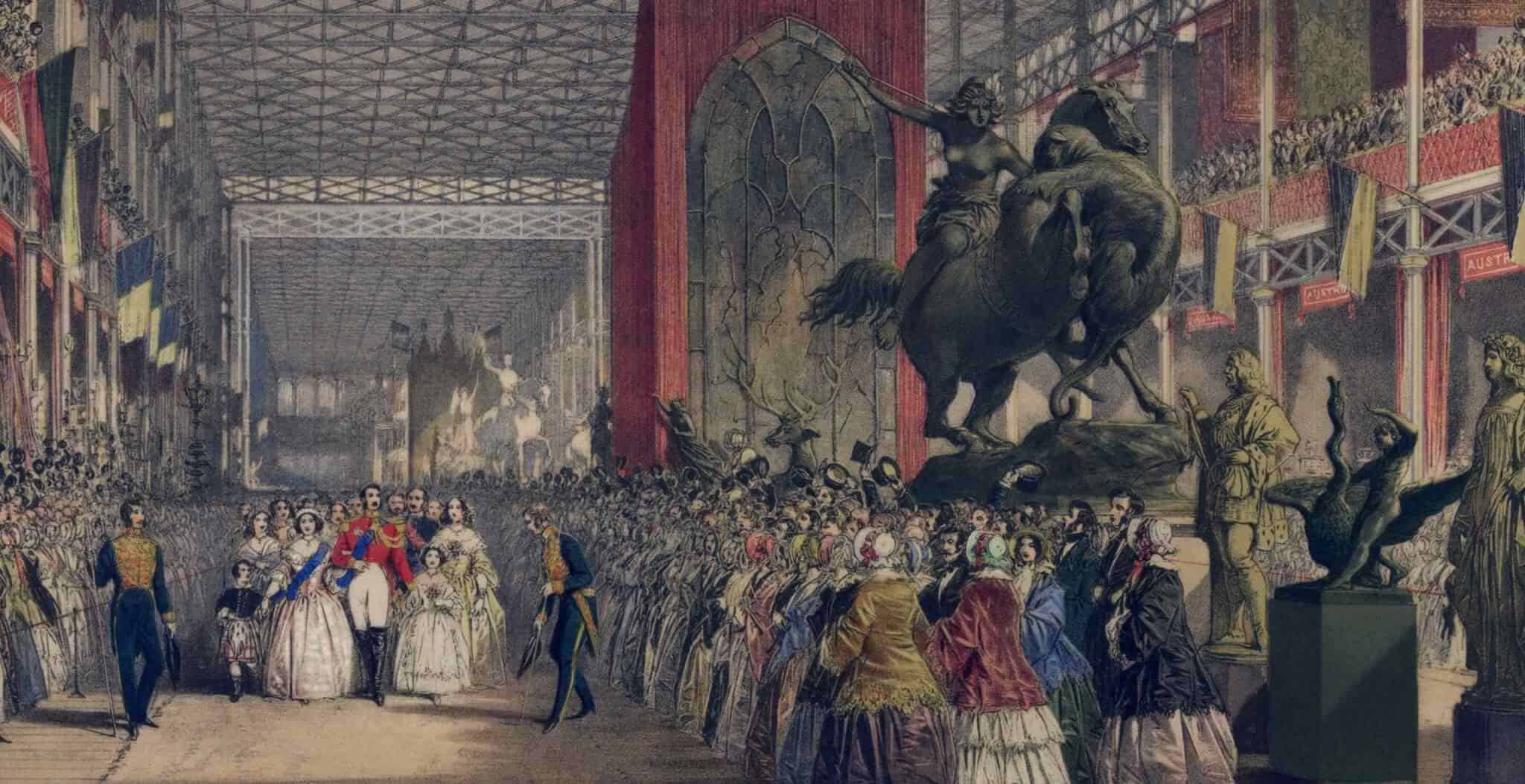

Once educated, Karim began work in a clerk position based at the jail in Agra where most of his family worked, including his father and brothers. This would also be the setting for meeting his wife. The superintendent of the jail in Agra was a man named John Tyler, who had the great honour of meeting the queen in 1886 at the Colonial and Indian Exhibition in London where he demonstrated the rehabilitation work of Indian inmates who had woven ornate Indian carpets. The queen was most impressed and made the request for Indian attendants.

The year of Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee 1887 was fast approaching and in this context, the newly christened Empress of India was looking for Indian attendants to assist her during the event.

On his return to India, Tyler chose Karim as one of the fortunate two Indians who were to be selected to become servants to Queen Victoria. The other servant to be chosen was Mohamed Buxshe, who unlike Karim, was a servant with a great deal of experience working for a British general. Karim’s lack of preparation for such an esteemed role led him to take a quick course before leaving for England whereby he would learn the basics in palace etiquette as well as the English language. He was also given a new set of clothes for the occasion.

As soon as he arrived in England, Karim appeared to make a great impression on Queen Victoria and after his formal duties for the jubilee concluded, he impressed her further when he surprised the monarch with a chicken curry which he made using spices brought over from Agra. At her summer residence, Osborne House on the Isle of Wight, the queen was delighted with the surprise dish which she described as ‘excellent’ and as a result it became a regular feature on the menu.

In her recently acquired title of Empress of India, the queen, who herself never visited the country, was keen to learn more about the rich and diverse lands in which she ruled and thus turned to Karim in order to find out more. Obliging the monarch, Karim soon began to teach her Urdu (Hidustani as it was then known) in one-on-one lessons which Victoria seemed eager to partake in, so much so that she recorded an entry in her journal detailing what she had learnt each day.

Karim likewise took English lessons and within a few months their contact became more direct and much more frequent. After bonding over a shared interest in languages, Victoria chose to promote him to the title of Munshi Hafiz Abdul Karim, thus delineating his role as her instructor but also making him an official Indian clerk.

Not long after arriving in this strange and foreign land, Abdul Karim had risen from the status of a humble servant to an Indian clerk and munshi to the queen. Unsurprisingly, their blossoming friendship caused consternation amongst other members of staff, a matter which over the years would gain increased traction within the royal household but which the queen herself chose to ignore at every opportunity.

Their unorthodox companionship was defended at every turn and any attack or slight against Karim, Victoria not only took personally but also chose to handle herself.

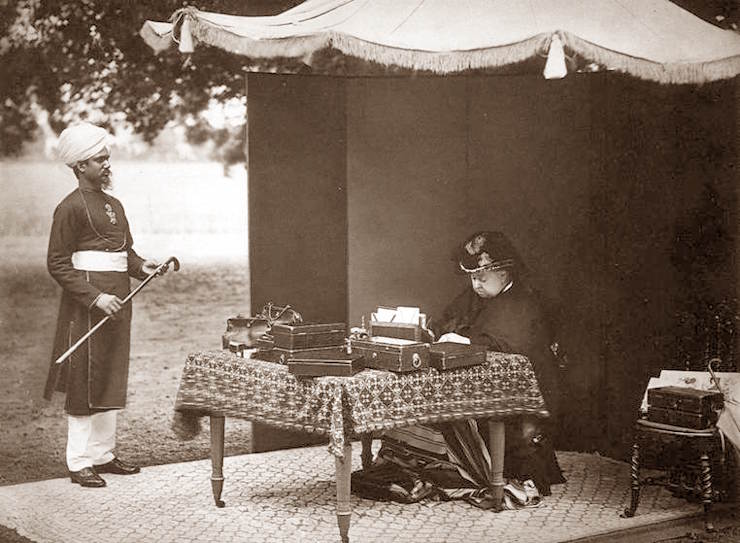

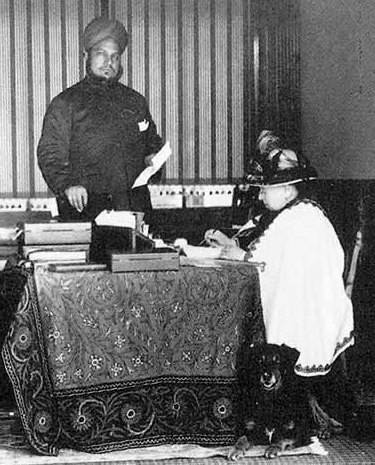

Queen Victoria, her collie dog Noble, and the Munshi, Abdul Karim. Published in the The Graphic, 16 October 1897 Taken in the Garden Cottage at Balmoral, 1897.

Queen Victoria, her collie dog Noble, and the Munshi, Abdul Karim. Published in the The Graphic, 16 October 1897 Taken in the Garden Cottage at Balmoral, 1897.

The close bond was not the first of its kind for the monarch, as earlier in her reign she enjoyed the company and the confidence of her Scottish servant John Brown. Their relationship, as noted by other members of staff, was incredibly tight, so much so that some in the household referred to her mockingly as ‘Mrs Brown’. Once her faithful Scottish servant had died in 1883, Queen Victoria felt an absence in her life which she now filled with Karim.

As their bond grew, so too did the privileges he enjoyed, which caused even further division amongst other members of staff. Karim whom she referred to as ‘closest friend’, was allowed to occupy the bedchambers of the former Mr Brown; he also invited his wife over to England on the insistence of Queen Victoria, who also extended the invitation to the rest of Karim’s family.

Other perks he enjoyed included riding around in his own personal carriage, a luxury afforded to only a chosen few, as well as being given access to the best seats at the opera and banquets, travelling with the queen as part of the royal party and having residences with his wife on the main royal estates in Britain. He could play billiards in the palaces and was allowed to carry a sword as well as wear his medals in court.

His family were on the receiving end of great privileges by extension, showing the willingness of Queen Victoria to entertain the entire family. He was also in receipt of land in India bestowed by the monarch and soon became her go to advisor on all matters concerning India.

The monarch soon began to take advice from him on political matters pertaining to India and so trusted his guidance on such important matters, that she would in turn demand answers from the viceroy in charge at the time, who became answerable to these new demands.

In many ways, Karim had greatly surpassed Mr Brown and his former influence on her life as the power he wielded was unheard of; not only was he afforded such great luxuries and privileges but his opinion now interfered in political matters and issues of governance.

Queen Victoria, despite antagonising many of those around her, remained steadfast in her support of Karim. In fact, she proudly put their friendship on display and defended his position from any attack.

His unrivalled status and lavish lifestyle however continued to draw unwanted attention. Not only did he enjoy the privilege of having homes at not just one royal palace but three, but also was granted land in Agra. His portraits adorned the walls of Osborne in the Isle of Wight and Victoria had him written up in the Court Circulars and local gazettes.

In one final great honour, Victoria stipulated that Karim was to be one of the principal mourners at her funeral, something which was only bestowed to her family members and closest friends.

The disdain and anger induced by her affections for Karim circulated throughout royal circles, with many associates feeling resentment at his position but also feeling that he was taking advantage of her goodwill towards him.

A combination of Karim’s genuine arrogance, continuous favours from the queen and the nineteenth century context of racial attitudes created what was for some, an intolerable situation. Whilst the queen was well aware of such hatred towards Karim, she did her upmost to defend him in no uncertain terms by calling out ‘race prejudice’ in a letter which declared her unwavering support for him.

Nevertheless, the protection she gave Karim could not last forever and so it came, when in 1901, Queen Victoria passed away, Karim’s life of abundance was quickly snatched away from him. As soon as her successor Edward VII came to the throne he ordered Karim to return to India and had all his correspondence with Victoria destroyed, or so he thought.

In reality, Karim and his nephew managed to retain important documents, such as personal correspondence and his diaries, which would later form the basis of what is now in the public domain. Edward VII oversaw the burning of letters and sent guards to Karim’s cottage in order to instruct his family to leave. It was essential at the time for the royal family to edit out this part of Queen Victoria’s legacy and did their very best at erasing Karim from public records.

In the meantime, Karim returned to India after his long and luxurious stay in England and retired to the estate which Victoria had arranged on his behalf. Having no children and having lost so much, the story of Karim’s close relationship with Queen Victoria died with him in 1909, as he passed away at the age of forty-six. It would be another one hundred years before details emerged from old diaries, retaining the most intricate details of their close bond.

Queen Victoria had seen in Abdul Karim something which no one else could see, a man that she could confide in, learn from, mother and instruct, and thus he received great honours and privileges which he could scarcely have conjured up in his imagination as a young boy back in India.

Jessica Brain is a freelance writer specialising in history. Based in Kent and a lover of all things historical.

Published: 23rd June 2025.

** 2017 film called ‘Victoria and Abdul’ starring Judi Dench and Ali Fazal.